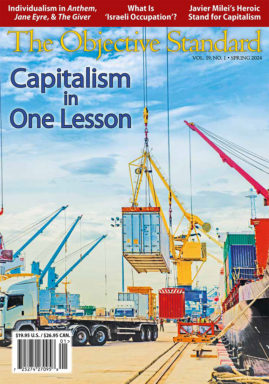

I recently spoke with Professor John Allison about his efforts and successes in creating pro-capitalist programs in American universities. Professor Allison was the CEO of BB&T for twenty years, during which time the company’s assets grew from $4.5 billion to $152 billion. He now teaches at Wake Forest University. —Craig Biddle

Photo courtesy of Wake Forest University

Craig Biddle: Hello, John, and thank you for joining me.

John Allison: It is a pleasure to be with you.

CB: Let me begin with a couple of questions about your work at Wake Forest. I understand that you joined the faculty in March 2009 as a Distinguished Professor of Practice—a fitting title given your decades of applying philosophy to business. What has your work at the university entailed so far? And how have your ideas been received?

JA: I’ve primarily been involved in teaching leadership both to students and to some of the administrators in the university. I taught a course on leadership last fall, and I’ve been participating in various courses taught by other professors on finance, mergers and acquisitions, and organizational development. But my focus is on leadership.

My ideas have been well received. The students take great interest in talking to someone who has been in the real world and been successful in business. I think they appreciate that perspective.

CB: Through the BB&T Charitable Foundation, you’ve established programs for the study of capitalism at a number of American universities. How many of these programs are there now? What unifies them? And what generally do they entail?

JA: BB&T has sponsored sixty-five programs to date, and they’re all focused on the moral foundations of capitalism. While many people recognize that capitalism produces a higher standard of living, most people also believe that capitalism is either amoral or immoral. Our academic question is: How can an immoral system produce a better outcome? We believe that capitalism is moral and that this is why it is so successful. We think it is critically important that we not only win the battle over economic efficiency, but that we engage in and win the debate over ethics as well.

These programs all have some of the same themes, but they are customized by the universities. We try to find professors who have a strong interest in the moral foundations of capitalism and use our program to support their work. Even though such professors are in a minority, most universities, particularly larger ones, have some pro-capitalist professors and are interested in providing capitalism with a fair hearing in the academic community. Typically, Atlas Shrugged is a required reading in a course on the ethical foundations of capitalism. It is important to us that all our programs meet the highest academic standards. We don’t think that you should try to indoctrinate students, nor do we think you can indoctrinate students. We do think that when students hear both points of view, the arguments for capitalism are extremely compelling.

One of the key goals of the programs is to help economists understand the philosophical justifications for capitalism and, vice versa, to help philosophers who support the ethical premises underlying a capitalist system understand the economics. Most free market economists view capitalism as a good system because it works. We believe capitalism works because it is good and that it is not surprising that a good system works.

Each summer we hold a conference at Clemson University for the professors involved in the BB&T programs. Last summer’s conference was attended by seventy professors. While most of our participants are either economists or business professors, there are a number of philosophers, political scientists, and historians. One of the values of the conference is having people from various disciplines discuss capitalism from their perspective, which deepens everyone’s understanding. The conference also serves to some extent as a support group. Pro-capitalist professors are generally outnumbered on university campuses, and talking to other intellectuals who share your fundamental beliefs is reinforcing.

It’s been impressive to watch the professors learn from each other through this process. This is the fifth year we’ve held the conference, and every year we’ve had more participants, engaged in deeper discussions, and generated more understanding.

CB: You mentioned that professors with an interest in the moral foundations of capitalism are in the minority. How did we get to the point where so few professors in, of all places, American universities, understand or have an interest in the moral foundations of freedom?

JA: If you look at how the United States went from embracing the philosophical principles of the Founding Fathers to where we are today, the major change has been the ability of the left to take over the universities. This happened by chance. In the late 1800s, most of the universities in America were dominated by traditional American thinkers—Founding Father–type thinkers. However, America was rising as an economic power, and American colleges wanted to be viewed as world-class universities. To accomplish this goal, they had to start issuing PhD degrees. But because they didn’t have any professors with PhDs, they didn’t have any professors who were theoretically qualified to teach at the PhD level. So they turned to Europe for PhD professors.

In science this was a home run. The universities were able to attract a lot of very smart PhD-level scientists. In the liberal arts, however, it was a disaster—particularly in philosophy.

The philosophers who came to America from Europe brought with them very destructive ideas—especially those of Immanuel Kant—the same ideas that led to Nazism and communism in Europe. Fortunately, the American sense of life filtered out some of those ideas, but the ones that got through caused a radical drift toward collectivism, socialism, statism, and away from the ideals of individual rights and a free society. Consequently, American universities today are dominated by people who are clearly left of center, and they are educating our future leaders. The only way we can restore recognition of and respect for the principles that made America great is to enter the debate in the universities and provide as many students as possible with an objective view of individual rights and free markets. We need to reach them before they go out into their careers and future leadership positions. So the battle for the universities is really the battle for the future of America.

CB: What is your vision for what the BB&T programs could become and accomplish over time? Where do you see these efforts ten or fifteen years down the road?

JA: Our goal is to take the program national, and in ten years I would hope that we could have programs at two hundred universities throughout the United States. To do that, we have to move beyond the BB&T Foundation, because BB&T basically supports programs in its own operating area in the mid-Atlantic and southeast states. So we’ve recently created a foundation that will be focused on raising funds to take BB&T-like programs to other universities outside of the BB&T operating area.

Frankly, when we started the Moral Foundations of Capitalism program, it was very hard to get into universities because most universities don’t think that capitalism is moral. However, our programs have been extremely successful. The students love the programs, the professors love the programs, the universities love the programs—so now we have more requests than we can fund. In some ways this is a good problem, but in the current economic environment it poses a real challenge.

Currently, about 15,000 students per year are involved in some aspect of the BB&T programs. Our goal is to have as many as 75,000 students a year involved in these programs. In addition, while we don’t target only the “best and brightest” students, we do try to have as many of the “best and brightest” students as possible in the programs. Student feedback has been extraordinarily positive because these courses are devoted to fundamental issues—individualism vs. collectivism, rational self-interest vs. altruism, reason as man’s means of knowledge, the proper role of government—as against the more narrow issues that are the focus of most university courses today.

Also, in many cases, the students are hearing a different perspective on capitalism for the first time because these are the first professors they’ve encountered who have a deep understanding of both the philosophy and economics of the capitalist system.

CB: One symptom of the widespread confusion about capitalism in today’s universities is the refrain that capitalism is to blame for the financial crisis and our economic woes. How do you counter this claim?

JA: Well, it’s simply factually incorrect. Government policy is the cause of the financial crisis. We don’t live in a free market in the United States; we live in a mixed economy, partly free, partly government controlled. The mixture varies by industry: technology might be 20 percent government controlled, 80 percent free; financial services is 70 percent government controlled, and 30 percent free. It’s not surprising that the most regulated industry, the financial services industry, is the one where we had the biggest problems.

The primary causes of the financial crisis were bad decisions made by the Federal Reserve combined with government housing policy—specifically Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the giant government-sponsored enterprises that would not have existed in a free market. The Federal Reserve created a rapid expansion in the money supply, which caused a huge misinvestment (a bubble) that primarily ended up in the housing market because of Freddie Mac’s and Fannie Mae’s affordable housing programs. While there are many complexities, the short story is that the Federal Reserve printed too much money, and that created a bubble, which ended up in the housing market because of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

It is true that individual financial institutions made bad decisions. In my opinion, they should have been allowed to go out of business—that would have been the proper way for them to be handled. However, their decisions were secondary to government policy. It should be remembered that the Federal Reserve owns the monetary system in the United States; we do not have a private monetary system. In 1913, our monetary system was nationalized. If you’re having problems in the monetary system—which is where the problems in the economy began—they are, by definition, government problems. This is analogous to interstate highway bridges falling down: If interstate highway bridges were falling down, everyone would recognize that the government owns the highways and conclude that this is a government-caused problem. Well, the government owns the monetary system, and the errors by the Federal Reserve are the foundations of the financial problems we’ve experienced.

CB: Unfortunately, even in the face of such a logical explanation of the political and economic causes of the financial crisis, many people maintain that the freer aspects of the economy must be to blame for the problems because freedom enables selfishness, and everyone “knows” that selfishness is evil. How do you address such objections?

JA: I have a presentation on principled leadership that examines the foundations for ethical behavior by individuals and organizations in a free society. It provides, I think, a very compelling defense for acting in one’s rational self-interest—properly understood. Many people perceive that taking advantage of other people is selfish. In fact taking advantage of other people is self-destructive. First, if you take advantage of others, very soon no one will trust you. You might fool Tom and Jane, but they will tell Dick and Harry, and soon you will be considered untrustworthy. In addition, trying to manipulate other people’s consciousness at the expense of reality is psychologically destructive.

The alternative we are offered is self-sacrifice. Self-sacrifice carried to the logical extreme is altruism, which is self-defeating as it requires you to go to the lowest level of human life. Since there are always people in the process of dying, the only way to be a good altruist is to live an extraordinarily poor life. Of course, there are very few real altruists, but altruism is used to make people feel guilty. A question I ask students: Do you have as much right to your life as anyone else has to theirs? Of course you do! Why would you believe anything different?

So, taking advantage of other people and self-sacrifice—neither one makes sense. The proper moral code for life and business is founded in the trader principle. We trade value for value. We get better together.

In our business, we help our clients achieve economic success and financial security, and they enable us to make a profit doing this. Life is about creating win-win relationships. There are only two stable relationship conditions: win-win and lose-lose. In any important relationship, you should ask what’s in it for you. You have the right to pursue your happiness. However, you should also ask what’s in it for them, because if there is no benefit to them, eventually the relationship will fail and become lose/lose.

I point out that acting in one’s self-interest requires holding the context. Many people view being selfish as taking advantage of others or having “tunnel vision,” that is, ignoring the world around them—both of which are self-destructive. To act in one’s long-term rational self-interest requires that you ask yourself what kind of world you would like to live in and what would you enjoy doing to create that world. For example, I contribute to the Ayn Rand Institute because it supports ideas that are vital to creating a free, productive society.

Acting in your rational self-interest requires that you have a clear sense of purpose, that you take care of your body (exercise, eat right, etc.), that you take care of your mind (read, study, think), that you create healthy relationships with people you value. The problem is not that people are too selfish, but rather that they don’t act in their rational self-interest and they don’t pursue happiness in the Aristotelian sense of that concept.

CB: Amen to that! Your work and the BB&T programs are crucial to the future of America. How can advocates of your efforts and these programs help?

JA: We’re certainly looking for money! Contributions to our new foundation, the Center for Excellence in Higher Education [9780 Lantern Road, Suite 150, Fishers, IN 46037], would be appreciated. In addition, we are actively seeking professors and schools that want to teach this material, so any leads on professors or universities that might be interested in the moral foundations of capitalism would be appreciated as well.

CB: Thank you for your time, John, and best of success with your vital programs.