Editor’s note: This article is an edited version by Michael Berliner of Dr. Ridpath’s article originally written for a 2005 project that was canceled. Because the article was written prior to the publication of A Companion to Ayn Rand, Allan Gotthelf and Greg Salmieri, eds. (New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016), it makes no reference to that book’s chapter on Nietzsche by Lester Hunt.

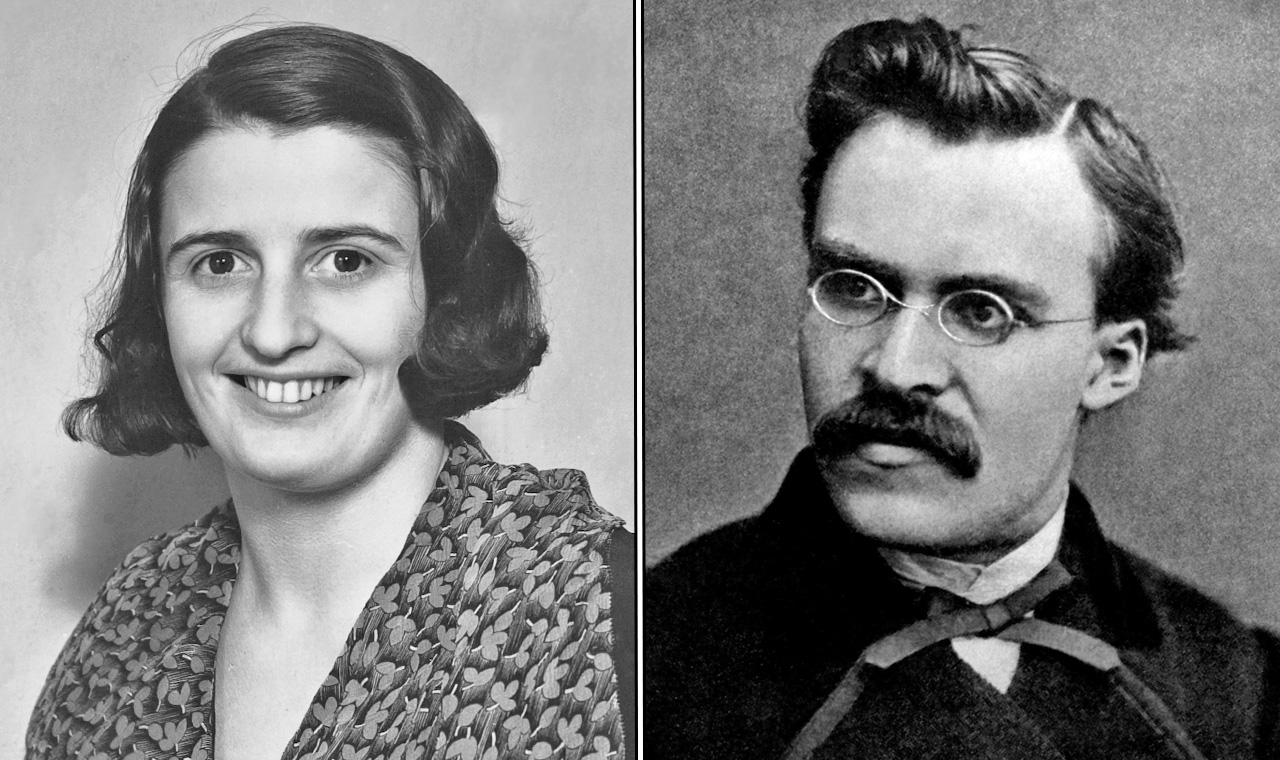

I disagree with [Nietzsche] emphatically on all fundamentals. —Ayn Rand (1962)1

I do not want to be confused with Nietzsche in any respect. —Ayn Rand (1964)2

Why was Ayn Rand determined to distance herself from Nietzsche? Because in her time, as today, various writers portrayed her as a Nietzschean, claiming that she embraced his ideas and modeled her characters accordingly—which she did not.

The notion of Rand as a Nietzschean was promulgated most viciously in Whittaker Chambers’s 1957 review of Atlas Shrugged, published in National Review. Although he acknowledged Rand’s debt to Aristotle, Chambers wrote that she is “indebted, and much more heavily, to Nietzsche” and that “her operatic businessmen are, in fact, Nietzschean supermen.”3 Since then, similar claims have been made in countless articles and books, including Goddess of the Market, in which Jennifer Burns declared that Rand’s “entire career might be considered a ‘Nietzschean phase.’”4

Was Rand influenced by Nietzsche? To some extent, yes. In the 1930s, she called him her “favorite philosopher” and referred to Thus Spake Zarathustra as her “bible.” As late as 1942, Nietzsche quotes adorned the first pages of each section of her manuscript of The Fountainhead. But from her first encounter with his ideas, Rand knew that her ideas were fundamentally different from his.

Rand first read Nietzsche in 1920, at the age of fifteen, when a cousin told her that Nietzsche had beaten her to her ideas. “Naturally,” Rand recalled in a 1961 interview, “I was very curious to read him. And I started with Zarathustra, and my feelings were quite mixed. I very quickly saw that he hadn’t beat me to [my ideas], and that it wasn’t exactly my ideas; that it was not what I wanted to say, but I certainly was enthusiastic about the individualist part of it. I had not expected that there existed anybody who would go that far in praising the individual.”5

However attracted to Nietzsche’s seeming praise of the individual, Rand had her doubts even then about his philosophy. As she learned more about philosophy and about Nietzsche’s ideas, she became increasingly disillusioned. “I think I read all his works; I did not read the smaller letters or epigrams, but everything that was translated in Russian. And that’s when the disappointment started, more and more.”6 The final break came in late 1942, when she removed her favorite Nietzsche quote (“The noble soul has reverence for itself”)7 from the title page of The Fountainhead. By this time, she had concluded that political and ethical ideas—including individualism—are not fundamental but rest on ideas in metaphysics and epistemology. And this is where the differences between her philosophy and that of Nietzsche most fundamentally lie.

Early Premises

The roots of both Nietzsche’s and Rand’s philosophies can be traced to their youths. . . .

You might also like

1. Ayn Rand, Q&A, “The Intellectual Bankruptcy of Our Age,” The Ayn Rand Program radio series, April 5, 1962, in Ayn Rand Answers, edited by Robert Mayhew (New York: New American Library, 2005), 117.

2. Ayn Rand, “Objectivism vs. Nietzscheanism,” Ayn Rand on Campus radio program, December 13, 1964.

3. Whittaker Chambers, “Big Sister Is Watching You,” National Review, December 28, 1957.

4. Jennifer Burns, Goddess of the Market (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 303n4.

5. Ayn Rand, interview by Barbara Branden, transcript 198, The Ayn Rand Archives, Irvine, CA.

6. Rand, interview, 200.

7. Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, translated by Walter Kaufmann (New York: Random House, 1989), 228.

8. Ayn Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It (New York: New American Library, 1984), 2.

9. Ayn Rand, Journals of Ayn Rand, edited by David Harriman (New York: Penguin, 1997), 698.

10. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, translated by Walter Kaufmann (New York: Random House, 1968), 549–50.

11. Friedrich Nietzsche, Philosophy during the Tragic Age of the Greeks, quoted in F. A. Lea, The Tragic Philosopher (London: Methuen: 1957), 46.

12. Heraclitus, B80.

13. Heraclitus, B53.

14. Nietzsche, Tragic Age of the Greeks, quoted in Lea, The Tragic Philosopher, 46.

15. Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, Book One, sec. 13, translated by Walter Kaufmann (New York: Random House, 1969), 45.

16. Nietzsche, Will to Power, quoted in G. A. Morgan, What Nietzsche Means (New York: Harper, 1965), 277.

17. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, quoted in Morgan, What Nietzsche Means, 61.

18. Nietzsche, Will to Power, quoted in Lea, The Tragic Philosopher, 285.

19. Nietzsche, Will to Power, quoted in Lea, The Tragic Philosopher, 212.

20. Nietzsche, Will to Power, quoted in Morgan, What Nietzsche Means, 118.

21. Nietzsche, Will to Power, quoted in Morgan, What Nietzsche Means, 63.

22. Ayn Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 2nd ed. (New York: New American Library, 1990), 29.

23. Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It, 29.

24. Ayn Rand, “Art and Cognition,” in The Romantic Manifesto (New York: New American Library, 1971), 46.

25. Leonard Peikoff, “The Analytic-Synthetic Dichotomy,” in Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 105.

26. Ayn Rand, “This is John Galt Speaking,” in Ayn Rand, For the New Intellectual (New York: New American Library, 1961), 126.

27. Leonard Peikoff, The Ominous Parallels (New York: New American Library, 1982), 51.

28. Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It, 25.

29. Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It, 25.

30. Nietzsche, Will to Power, quoted in Morgan, What Nietzsche Means, 50.

31. Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, in Nietzsche, The Portable Nietzsche, translated by Walter Kaufmann (New York: Penguin, 1968), 495. For Rand’s view that philosophical ideas are the ultimate cause of and explanation for history, see the title essay in her Philosophy: Who Needs It.

32. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 23–24.

33. Nietzsche, Will to Power, 268.

34. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 24.

35. Nietzsche, The Dawn, quoted in R. C. Solomon, Nietzsche: A Collection of Critical Essays (University of Notre Dame, 1980), 302.

36. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 213–14.

37. Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, 500.

38. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, quoted in Solomon, Nietzsche: A Collection of Critical Essays, 133.

39. Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 44.

40. Ayn Rand, “Playboy Interview,” Playboy, March 1964.

41. Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It, 17.

42. Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It, 27.

43. Rand, New Intellectual, 122.

44. Rand, New Intellectual, 120.

45. Rand, New Intellectual, 14–15.

46. Rand, Journals, 68.

47. Rand, interview, 198.

48. Rand, interview, 199.

49. Rand, interview, 200–201.

50. Nietzsche, “Notes,” in The Portable Nietzsche, 458.

51. Nietzsche, “On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense,” in The Portable Nietzsche, 42–43.

52. Nietzsche, Birth of Tragedy, quoted in Solomon, Nietzsche: A Collection of Critical Essays, 87.

53. Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human, quoted in Solomon, Nietzsche: A Collection of Critical Essays, 91.

54. Nietzsche, Will to Power, 298.

55. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, quoted in W. T. Jones, A History of Western Philosophy, vol. 4 (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1975), 242.

56. Nietzsche, The Gay Science, translated by Walter Kaufmann (New York: Random House, 1974), 84–85.

57. Nietzsche, Gay Science, 177.

58. Nietzsche, Gay Science, 299–300.

59. Nietzsche, Gay Science, 172.

60. Nietzsche, Gay Science, 170.

61. Nietzsche, The Dawn, quoted in Graham Parkes, Composing the Soul: Reaches of Nietzsche’s Psychology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 8.

62. Rand, interview, 112.

63. Rand, Journals, 66–68.

64. Rand, Letters of Ayn Rand, edited by Michael S. Berliner (New York: Penguin, 1995), 356.

65. Ayn Rand, “Brief Summary,” in The Objectivist, September 1971, 1.

66. Rand, interview, 200.

67. Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It, 62.

68. Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 29.

69. Rand, New Intellectual, 124.

70. Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 1.

71. Ayn Rand, Virtue of Selfishness (New York: New American Library, 1964) 19–20.

72. Rand, Romantic Manifesto, 17.

73. Rand, New Intellectual, 126.

74. Leonard Peikoff, “Nazism and Subjectivism,” The Objectivist, February 1971, 12.

75. Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 79.

76. Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 35.

77. Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, 63.

78. Peikoff, Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand (New York: Penguin, 1993), 174.

79. Ayn Rand, The Voice of Reason (New York: New American Library, 1988), 89.

80. Rand, New Intellectual, 162.

81. Nietzsche, Genealogy, Preface, 15–16.

82. Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human, quoted in Richard Schact, Nietzsche (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983), 429.

83. Nietzsche, The Antichrist, in The Portable Nietzsche, 577.

84. Nietzsche, Will to Power, 145.

85. Nietzsche, Ecce homo, Book 4, translated by Thomas Wayne (New York: Algora, 2004), 97.

86. Nietzsche, Genealogy, First essay, 36.

87. This is the subtitle of The Will to Power, also the working title of Nietzsche’s last (and unfinished) book.

88. The subtitle of Twilight of the Idols is “How One Philosophizes with a Hammer.”

89. Nietzsche, Ecce homo, Book 4, 90.

90. Nietzsche, Will to Power, 503.

91. Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra, in The Portable Nietzsche, 132.

92. Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra, in The Portable Nietzsche, 124.

93. Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra, in The Portable Nietzsche, 127.

94. Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra, quoted in Morgan, What Nietzsche Means, 183.

95. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 27

96. Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, 542.

97. Nietzsche, Will to Power, 513.

98. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 215.

99. Nietzsche, “Notes for Thus Spake Zarathustra,” quoted in Lea, The Tragic Philosopher, 202.

100. Nietzsche, Will to Power, 287, 162.

101. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 24.

102. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 13.

103. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 17–18.

104. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 27.

105. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, x.

106. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 34.

107. Nietzsche, Will to Power, 199.

108. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 34.

109. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, vii.

110. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, xi.

111. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 28.

112. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 29.

113. Rand, New Intellectual, 130–31.

114. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 28.

115. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 28.

116. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 28.

117. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 28.

118. Nietzsche, Genealogy, Second essay, 59–60.

119. Nietzsche, Will to Power, 403.

120. Nietzsche, Complete, quoted in Morgan, What Nietzsche Means, 363.

121. Nietzsche, “Notebooks,” quoted in Morgan, What Nietzsche Means, 360.

122. Nietzsche, Will to Power, 495–96.

123. Nietzsche, Will to Power, quoted in Morgan, What Nietzsche Means, 182.

124. Nietzsche, “The Greek State,” quoted in Lea, The Tragic Philosopher, 63.

125. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 201.

126. Nietzsche, Genealogy, Second essay, 78.

127. Nietzsche, quoted in Morgan, What Nietzsche Means, 192.

128. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 118.

129. Nietzsche, Will to Power, 467.

130. Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, 118. These are merely different translations from the German.

131. Nietzsche, “Notes for Zarathustra,” quoted in Solomon, Nietzsche: A Collection of Critical Essays, 150.

132. Nietzsche, Genealogy, Second essay, 65.

133. Ayn Rand, Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal (New York: New American Library, 1967), vii.

134. Rand, New Intellectual, 78.

135. Rand, Capitalism, 311–12.

136. Rand, Voice of Reason, 234.

137. Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It, 31.

138. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 150.

139. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 36.

140. Rand, Capitalism, 17.

141. Rand, New Intellectual, 134.

142. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 110.

143. Rand, Virtue of Selfishness, 113.

144. Ayn Rand, Return of the Primitive (New York: Penguin, 1999), 84.

145. Rand, Philosophy: Who Needs It, 146.

146. Ayn Rand, “Textbook of Americanism,” in The Ayn Rand Column, 2nd ed., edited by Peter Schwartz (New Milford, CT: Second Renaissance Books, 1998), 84.

147. Rand, Romantic Manifesto, 163.

148. Ayn Rand, “About the Author,” in Atlas Shrugged (New York: Penguin, 1992), 1075.

149. Rand, Letters, 236.

150. Rand, Atlas Shrugged, 725.

151. Rand, New Intellectual, 36.