In the years 1942–1943, at the height of the Nazi reign of terror, a group of idealistic young Germans rose to challenge Hitler’s regime. They published a series of pamphlets that upheld, in ringing terms, love of freedom and a call to end Nazi brutality. In reference to the moral purity of their cause, they dubbed themselves the “White Rose.”

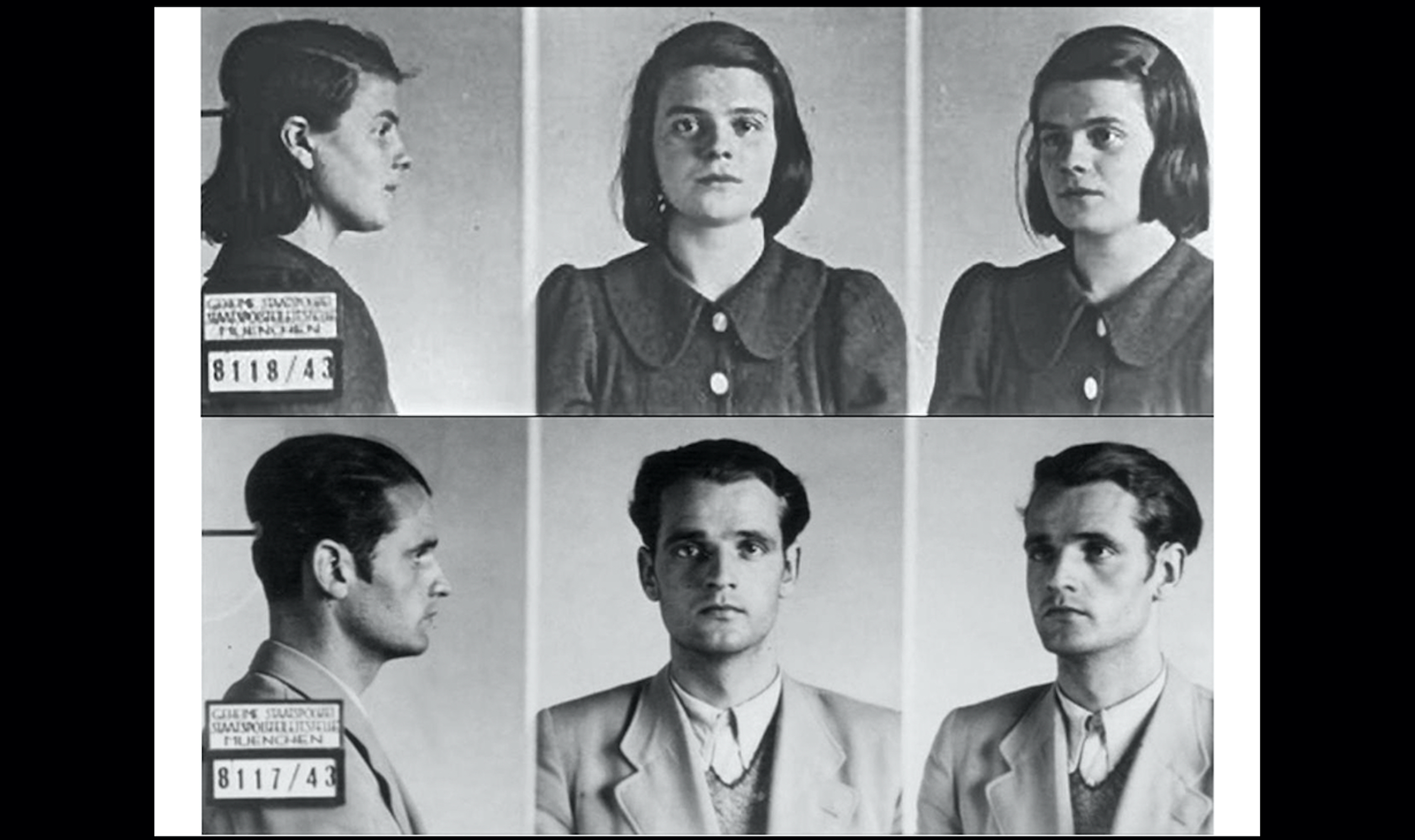

The core members of the White Rose were students at the University of Munich, including medical student and German Army veteran Hans Scholl; his younger sister, Sophie Scholl; Alexander Schmorell; Willi Graf; and Christoph Probst—and a philosophy professor who became their mentor, Kurt Huber. Together, they dedicated themselves to fighting Nazi oppression, come what may.

In 1933, Hitler and the National Socialist (Nazi) Party came to power in Germany. The Nazis held that “Aryans” (specifically, northern European whites) were a morally superior race; that their moral superiority consisted, in part, of a willingness to sacrifice themselves for the “volk” (people); and that this “master race” had the moral authority to conquer, enslave, or annihilate “inferior races.” The Nazis targeted, as their primary enemies, the Jews, who they held to be arrant egoists, unwilling to sacrifice for the volk. “Deutschland uber alles,” the Nazis proclaimed, meaning “Germany above all.” By this, they meant that Germany had moral authority to conquer and subordinate other nations—and to subjugate all individuals to the German state, which, they held, had absolute power. According to Nazi philosophy, individuals—German or foreign—have no rights; they have only the moral obligation to selflessly serve the German state.1

Hans Scholl, born September 22, 1918, was a teenager when he joined the Hitler Youth in 1933, an organization devoted to indoctrinating young Germans in Nazi beliefs. He quickly became disillusioned and quit.2 The Gestapo—the dreaded Nazi secret police—imprisoned him for two weeks in late 1937 for organizing a (pre-White Rose) youth group dedicated to countering National Socialist principles.3

On September 1, 1939, Hitler’s armies invaded Poland, precipitating World War II. In May 1940, Scholl, then twenty-one, was drafted into the military and deployed as a medical orderly on the French front.4 In April 1941, he was allowed to return to university and continue his medical studies.

In late June or early July 1942, Scholl and several other young dissidents formed the White Rose, determined to fight Nazi “crime[s] against human dignity.” They were disgusted by the fact that so many German civilians simply conformed to the vicious will of the National Socialist Party—and that almost none dared to speak out against its barbarity. They hoped that if the group could reach a broad audience with their message, morally upright Germans would resist the Nazis. So, in June 1942, they began publishing leaflets excoriating the Nazis’ moral atrocities.

Their first leaflet said, in part:

Isn’t it true that every honest German is ashamed of his government these days? Who among us has any conceptions of the dimensions of shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible of crimes—crimes that infinitely outdistance every human measure—reach the light of day.5

Their second leaflet was even more vociferous, saying:

Since the conquest of Poland, 300,000 Jews have been murdered in this country in the most bestial way. . . . The German people slumber on in dull, stupid sleep and encourage the fascist criminals. Each wants to be exonerated of guilt, each one continues on his way with the most placid, calm conscience. But he cannot be exonerated; he is guilty, guilty, guilty!6

They stood up courageously for the rights of Nazi victims: “Here we see the most frightful crime against human dignity, a crime that is unparalleled in the whole of history. For Jews, too, are human beings.”7 Once, while aboard a German train, Scholl saw a young Jewish girl—wearing the yellow Star of David mandated by the Nazis—at hard labor. Running from his slow transport, he gave the girl a chocolate bar from his rations and a daisy for her hair.8

Nor was the White Rose afraid to condemn Hitler directly: “Every word that comes from Hitler’s mouth is a lie.”9 In their third leaflet, they wrote:

Why do you allow these men who are in power to rob you step by step, openly and in secret, of one domain of your rights after another, until one day nothing, nothing at all will be left but a mechanised state system presided over by criminals and drunks. Is your spirit already so crushed by abuse that you forget it is your right . . . to eliminate this system?10

The group also addressed their fellow students. In their fourth leaflet, they wrote, “We will not be silent. . . . We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace!”11

Their sixth leaflet said, “Fellow students . . . the day of reckoning [has come] for the most contemptible tyrant our people has ever endured.”12 In February 1943, Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, and Willi Graf painted in bold letters on the walls of the University of Munich, “Down with Hitler!,” “Freedom!,” and “Hitler the mass murderer!”13 Shortly after, a campus maintenance worker observed them with leaflets and turned them in. On February 18, 1943, they were arrested by the Gestapo.

Unsurprisingly, their trial was a farce. The Nazi judge did not permit the defendants to speak. Nevertheless, Sophie Scholl shouted out at the judge, “You know as well as we do that the war is lost. Why are you so cowardly that you won’t admit it?” The Scholl siblings and Christoph Probst were convicted and sentenced to death. On February 22, 1943, a mere four days after their arrest, they were executed by guillotine. As the blade fell, Hans Scholl’s voice rang out, “Long live freedom!” Alexander Schmorell and Kurt Huber were executed a few months later, in July 1943; Willi Graf, that October.14

But the Nazi murderers could not extinguish the White Rose’s message. Hans Konrad Leipelt and his girlfriend, Marie-Luise Jahn, who were friends with the Scholl siblings, received a copy of the White Rose’s sixth leaflet in late February 1943. They typed up copies—retitled And Their Spirit Lives On—and distributed them throughout Hamburg. In late autumn 1943, they were reported to the Gestapo for raising money for the widow of Kurt Huber. On October 13, 1944, Leipelt was sentenced to death for treason and guillotined on January 29, 1945.15 Jahn was sentenced to twelve years in a labor prison camp.

However, the White Rose’s sixth leaflet also was smuggled through Scandinavia to Britain by German jurist Helmuth James Graf von Moltke. In mid-1943, Allied planes dropped millions of copies of the leaflet, now retitled The Manifesto of the Students of Germany, on German towns and cities.16

Thus, the White Rose lived on.

Despite their extraordinary heroism, the White Rose has remained largely unknown in the United States, mentioned only in a few admiring articles. One was published on February 22, 1993, the fiftieth anniversary of the execution of Probst and the Scholl siblings. In the Long Island newspaper Newsday, Lillian Garrett-Groag memorialized these brave souls, saying,

It is possibly the most spectacular moment of resistance that I can think of in the twentieth century. . . . The fact that five little kids, in the mouth of the wolf, where it really counted, had the tremendous courage to do what they did, is spectacular to me.17

In the same Newsday article, Holocaust scholar Jud Newborn said, “You cannot really measure the effect of this kind of resistance in whether or not x number of bridges were blown up or a regime fell. . . . The White Rose really has a more symbolic value, but that’s a very important value.”18

The members of the White Rose were mostly students. They were young. They knew that death at the hands of the Gestapo was the most likely outcome for all of them. They fought for freedom anyway. At their trials and executions, they did not cower in the face of a brutal death. They were truly the bravest of the brave, going way beyond what virtually all of their countrymen did in support of human life and liberty. To say they deserve our greatest admiration is to speak in pale approximations. Such stories cause me, a principled atheist, to hope that there exists a glorious afterlife for such fallen heroes.

Philosopher and novelist Ayn Rand, escapee from an equally murderous regime, called upon men of reason to never sanction—in words, actions, or placid silence—any such brutal dictatorship. She spoke of young Soviet dissidents incarcerated for speaking out. One such, Vadim Delone, told his judge, “For three minutes on Red Square I felt free. I am glad to take your three years for that.”19 Rand said that if the protests against Soviet atrocities were sufficiently widespread, they could possibly save the condemned. She concluded that “one can never tell in what way or form some feedback from such a protest might reach the lonely children in Red Square.”20

In the aforementioned Newsday article, Lillian Garrett-Groag, perhaps unable to fully comprehend what the White Rose accomplished, said of the group, “I know that the world is better for them having been there, but I do not know why.”21 As Rand illumines, it is because they are heroes. In addition to their life-promoting accomplishments, such heroes show us the elevated moral stature possible and appropriate to human beings. They show us that human beings can choose not to be Nazis, monsters, murderers. We can choose instead to be moral exemplars in the cause of freedom and human life. Such heroes inspire us to be the best versions of ourselves. And, as Newborn glimpsed, this is the symbolic value of the lives—and deaths—of the White Rose.

Click To Tweet

You might also like

Endnotes

1. Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, translated by Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1943), 290, 297, 298, 301, 302.

2. “Hans Scholl,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Scholl (accessed May 1, 2020).

3. “Hans Scholl,” German Resistance Memorial Center, https://www.gdw-berlin.de/en/recess/biographies/index_of_persons/biographie/view-bio/hans-scholl/ (accessed May 4, 2020).

4. “Hans Scholl,” German Resistance Memorial Center.

5. “White Rose,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_Rose (accessed April 22, 2020).

6. “White Rose,” Wikipedia.

7. Richard Hurowitz, “Remembering the White Rose,” New York Times, February 21, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/21/opinion/white-rose-hitler-protest.html.

8. Hurowitz, “Remembering the White Rose.”

9. Hurowitz, “Remembering the White Rose.”

10. “White Rose,” Wikipedia.

11. Lawrence Ludlow, “We Are Your Bad Conscience,” Future of Freedom Foundation, February 1, 2007, https://www.fff.org/explore-freedom/article/bad-conscience/.

12. “White Rose,” Wikipedia.

13. Erin Blakemore, “The Secret Student Group That Stood up to the Nazis,” Smithsonian Magazine, February 22, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/the-secret-student-group-stood-up-nazis-180962250/.

14. “White Rose,” Wikipedia.

15. “White Rose,” Wikipedia.

16. “Hans Scholl,” Wikipedia.

17. “Hans Scholl,” Wikipedia.

18. “Hans Scholl,” Wikipedia.

19. Henry Kamm, New York Times, 1968, reprinted in Ayn Rand, “The Inexplicable Personal Alchemy,” in The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution (New York: New American Library, 1971), 117.

20. Rand, “Inexplicable Personal Alchemy,” 126.

21. “Hans Scholl,” Wikipedia.