The phrase in vogue today with advocates of minimum wage laws—laws forcing employers to pay employees more than they otherwise would—is “living wage.” But, apart from laws mandating a minimum wage, this phrase has no referent in reality. And laws dictating minimum wages are immoral.

The phrase in vogue today with advocates of minimum wage laws—laws forcing employers to pay employees more than they otherwise would—is “living wage.” But, apart from laws mandating a minimum wage, this phrase has no referent in reality. And laws dictating minimum wages are immoral.

To get a sense of how widespread are calls for a so-called “living wage,” consider some recent news stories:

- Some fast-food workers are “demanding $15.00 per hour” for their work, and recently many such workers walked off the job to show they’re serious. Some call that rate a “living wage.”

- California legislators recently passed a bill raising the state’s minimum wage from $8 per hour to $10 per hour by 2016. In this case, that is the so-called “living wage.”

- “The Milwaukee County Board will take up a living-wage ordinance this fall”—the rate in this case would fluctuate according to “federal poverty guidelines.”

- The District of Columbia considered (and rejected) a bill to force “Wal-Mart and other large retailers . . . to pay their employees a ‘living wage’ of at least $12.50 an hour.”

The fact that no one can agree on what a “living wage” is—is it $10, $12.50, $15, or some other number plucked from the air?—indicates that the phrase is totally arbitrary.

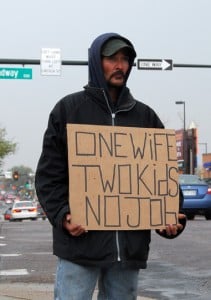

If the phrase means anything in literal terms, it would have to mean a subsistence wage. But no advocate of the so-called “living wage” wants to forcibly reduce wages to that required for mere subsistence. Instead, everyone who advocates a “living wage” wants to force employers to pay workers more than they currently do. (Although minimum wage laws would be immoral in any case, the fact is that most people who earn the minimum wage don’t supply the sole income on which their household is living, anyway.)

What advocates of a “living wage” are really after is an arbitrarily set wage floor—a legally mandated minimum that employers must pay employees regardless of all relevant facts pertaining to their businesses.

The economic case against the minimum wage is well known and easy to grasp (see, for example, recent articles by David Boaz and Thomas Sowell). If the government forces employers to pay employees more than their work is worth to employers, then employers will either refrain from hiring the potential employees or fire those who don’t provide value in excess of the legally mandated minimum wage. Thus, one consequence of minimum wage laws is that many people—particularly the young and inexperienced—end up out of work completely and, of course, are therefore unable to gain work experience and earn higher wages in the future.

Moreover, when the government forces up the costs of doing business, affected businesses must either scale back their operations or pass along the costs to their customers. This means, among other things, that wage controls force people (including the poor) to pay more for the food, clothes, medications, and other goods and services they consume.

But the economic harms that minimum wages impose do not stop advocates of such laws or even give them pause. Why? People who advocate minimum wage laws do so not because of their economic beliefs but because of their moral beliefs.

The (allegedly) moral premise behind minimum wage laws is altruism, the notion that being moral consists in sacrificing for others. On this premise, employers have a duty to sacrifice their own interests for the benefit of their employees—and government has a responsibility to force employers to act in accordance with this duty. According to altruism, business owners who act to maximize their profits thereby act immorally and must be forced to operate their businesses (at least in part) in accordance with the duty to sacrifice.

But, as a matter of demonstrable moral fact, business owners do not have a duty to sacrifice their interests for the sake of their employees, and they should not be forced to do so. The owner of a business, having built it or bought it, owns the business; he has a moral right to run it in accordance with his own judgment; and he has a moral right to hire employees on voluntary terms that make sense to both parties, given their needs, goals, and circumstances.

But, as a matter of demonstrable moral fact, business owners do not have a duty to sacrifice their interests for the sake of their employees, and they should not be forced to do so. The owner of a business, having built it or bought it, owns the business; he has a moral right to run it in accordance with his own judgment; and he has a moral right to hire employees on voluntary terms that make sense to both parties, given their needs, goals, and circumstances.

Of course, to run their businesses successfully, employers must offer competitive wages that attract, keep, and motivate quality workers. Likewise, to keep their jobs and earn higher wages over time, employees must provide their employers with value for value received. Thus, voluntarily agreed upon wages create a win-win, virtuous cycle in which both employer and employee can profit more and more over time. If at any time either the employer or the employee thinks that the relationship is no longer in his best interest, he is properly free to terminate it (in accordance with the terms of their agreements).

If an employee wants to earn a higher wage, it is his responsibility to gain the skills required to negotiate a higher wage in a competitive market. An employee should not seek a higher wage through government force; he should seek it by earning it, by trading value for value.

The main thing standing in the way of an unskilled employee gaining the work experience necessary to earn an entry-level wage, and then a mid-level wage—and so on, as high as his skills can carry him—are the clearly crippling minimum wage laws. Far from being raised, all minimum wage laws should be condemned as immoral and abolished.

Like this post? Join our mailing list to receive our weekly digest. And for in-depth commentary from an Objectivist perspective, subscribe to our quarterly journal, The Objective Standard.

Related:

- The Creed of Sacrifice vs. The Land of Liberty

- Atlas Shrugged and Ayn Rand's Morality of Egoism

- Minimum Wage Laws: Economically Harmful Because Immoral