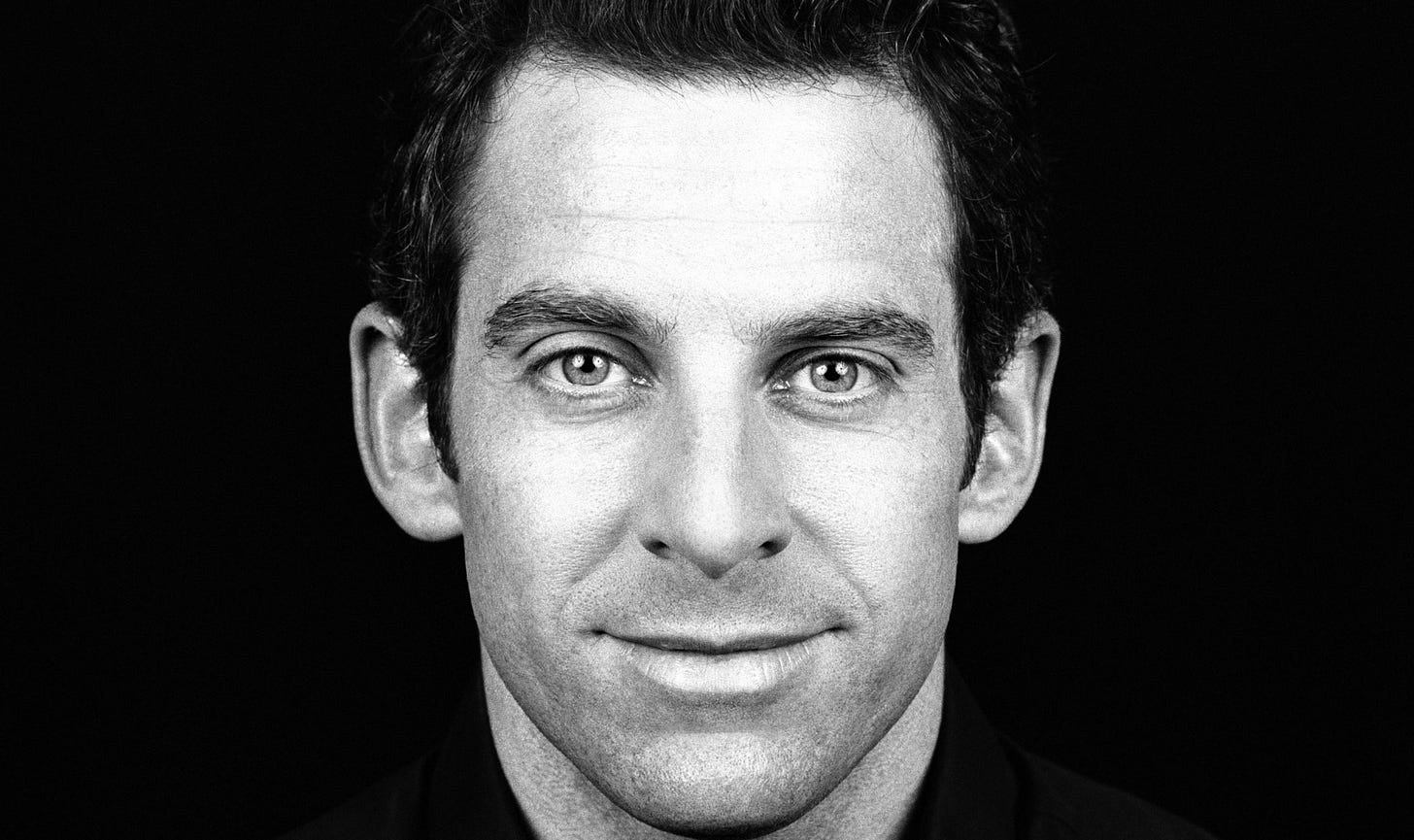

Why is it that Sam Harris, a committed utilitarian, sometimes sounds a bit like an egoist?

In my recently published essay “Sam Harris’s Failure to Formulate a Scientific Morality,” I point out that Harris upholds as his standard of moral value the utilitarian precept of the greatest good (or happiness) for the greatest number.

Harris’s utilitarian ethics …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Objective Standard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.