Was Abraham Lincoln, as most Americans believe, a defender of individual rights, a foe of slavery, and a savior of the American republic—one of history’s great heroes of liberty? Or was he a tyrant who turned his back on essential founding principles of America, cynically instigated the bloody Civil War to expand federal power, and paved the way for the modern regulatory-entitlement state?

In the face of widespread popular support for Lincoln (note, for example, the success of the 2012 Steven Spielberg film about him) and his perennially high reputation among academics, certain libertarians and conservatives have promoted the view that Lincoln was a totalitarian who paved the way for out-of-control government in the 20th century.1 Those critics are wrong. Contrary to their volumes of misinformation and smears—criticisms that are historically inaccurate and morally unjust—Lincoln, despite his flaws, was a heroic defender of liberty and of the essential principles of America’s founding.

Getting Lincoln right matters. It matters that we know what motivated Lincoln—and what motivated his Confederate enemies. It matters that we understand the core principles on which America was founded—and the ways in which Lincoln expanded the application of those principles. It matters that modern advocates of liberty properly understand and articulate Lincoln’s legacy—rather than leave his legacy to be distorted by antigovernment libertarians (and their allies among conservatives), leviathan-supporting “progressives,” and racist neo-Confederates.

My purpose here is not to present a full biographical sketch of Lincoln, nor to detail all types of criticisms made against him. Rather, my goal is to present sufficient information about Lincoln and his historical context to answer a certain brand of his critics, typified by Ron Paul, formerly a congressman from Texas and a contender for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination in 2008 and 2012. Paul and his ilk characterize Lincoln’s engagement of the Civil War as a “senseless” and cynical power grab designed to wipe out the “original intent of the republic.”2 Such claims are untrue and unjust, as we will see by weighing them in relation to historical facts. Toward that end, let us begin with a brief survey of claims by Lincoln’s detractors.

The revision of Lincoln and his legacy began in earnest soon after the Civil War, but, at the time, it was relegated to the intellectual swamp of Confederate memoirs and polemics. What was once the purview of a defeated and demoralized rump and of early anarchists such as Lysander Spooner has picked up steam within the modern libertarian movement.

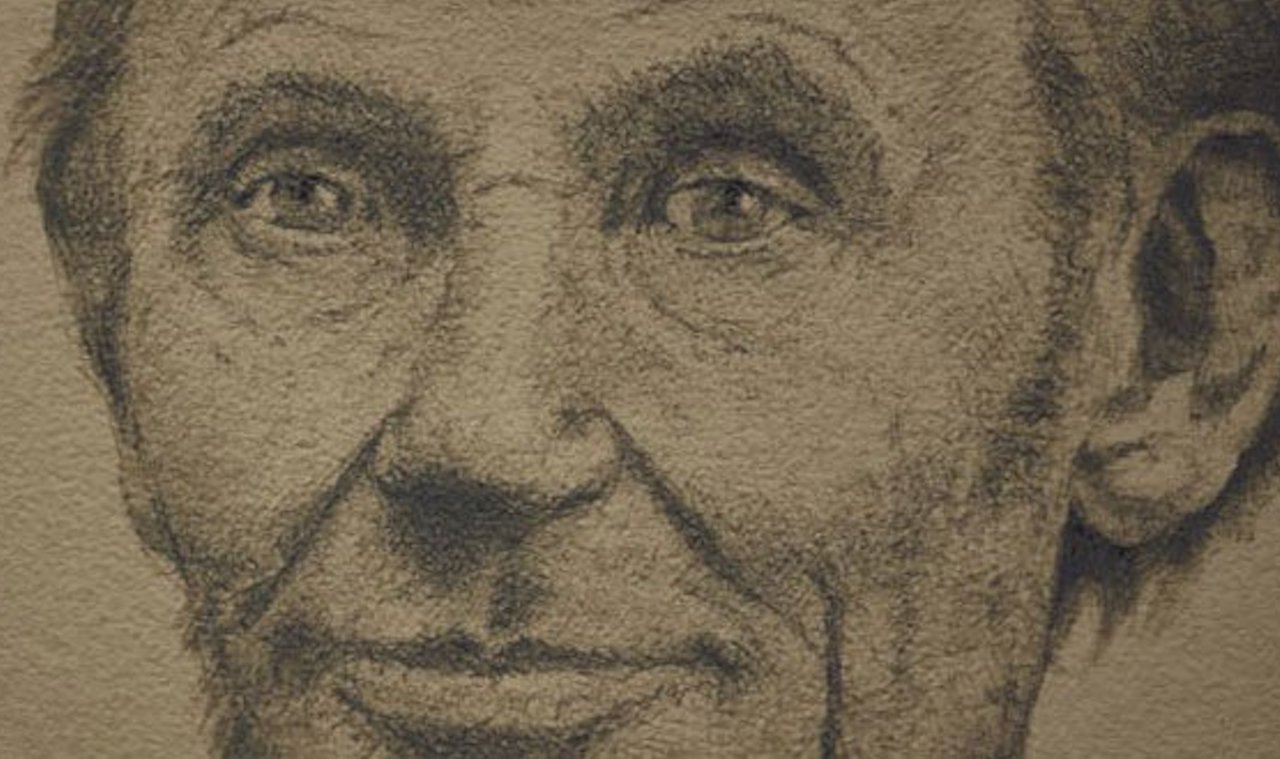

Lincoln, by Daniel Wahl

In the early 20th century, the acerbic newspaperman and social critic H. L. Mencken seriously suggested that the Confederates fought for “self-determination” and “the right of their people to govern themselves.” He claimed that a Confederate victory would have meant refuge from a northern enclave of “Babbitts,” the attainment of a place “to drink the sound red wine . . . and breathe the free air.”3 Mencken’s musings were but a symptom of a broader change in how many Americans came to view the Civil War. The conflict was no longer “the War of the Rebellion,” but “the War between the States.” The Confederate cause was no longer an essentially vile attempt to preserve slavery, but an honorable attempt to preserve autonomous government. Not coincidentally, during this period, Confederate sympathizers built monuments to the Confederacy throughout the South, and D. W. Griffith’s openly racist silent film The Birth of a Nation presented revisionist Civil War history and contributed to the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan.4 Sometimes Confederate sympathizers claimed that the Civil War was not really about slavery; other times they claimed that slavery was a glorious institution the South sought to preserve.

More recently, Murray N. Rothbard—widely regarded as the godfather of the modern libertarian movement (and someone who saw Mencken as an early libertarian)5—characterized the Civil War as the fountainhead of the modern regulatory state:

The Civil War, in addition to its unprecedented bloodshed and devastation, was used by the triumphal and virtually one-party Republican regime to drive through its statist, formerly Whig, program: national governmental power, protective tariff, subsidies to big business, inflationary paper money, resumed control of the federal government over banking, large-scale internal improvements, high excise taxes, and, during the war, conscription and an income tax. Furthermore, the states came to lose their previous right of secession and other states’ powers as opposed to federal governmental powers. The Democratic party resumed its libertarian ways after the war, but it now had to face a far longer and more difficult road to arrive at liberty than it had before.6

Thomas DiLorenzo, a colleague of Rothbard’s until Rothbard’s death in 1995, penned two books responsible for much of today’s libertarian and conservative antagonism toward Lincoln: The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (2002) and Lincoln Unmasked: What You’re Not Supposed to Know About Dishonest Abe (2006). (Both DiLorenzo and Ron Paul are senior fellows of the Ludwig von Mises Institute, an organization that, while bearing the name of the great Austrian economist von Mises, is more closely aligned with Rothbard’s anarchist views.)

Largely through his influence on popular economist Walter E. Williams, who wrote the foreword to DiLorenzo’s 2002 book, DiLorenzo has reached a relatively wide audience of libertarians and conservatives. Williams is known to many as a genial guest host for The Rush Limbaugh Show, a fellow of the Hoover Institute, and a distinguished professor of economics at George Mason University. He gave his imprimatur to DiLorenzo’s work, thereby elevating what might otherwise have been a peculiar book from the depths of Rothbard’s libertarian, paleoconservative, neo-Confederate intellectual backwater to a nationally known and provocative piece of severe Lincoln revisionism.

What are the essential criticisms leveled against Lincoln by such writers as Mencken and DiLorenzo? The most important of these criticisms can be grouped into four categories. First, these critics claim, Lincoln eviscerated the right of secession supposedly at the heart of the American Revolution. Second, say the critics, Lincoln did not truly care about slavery; he invoked it only to mask his real reasons for pursuing war—to expand the power of the federal government. Anyway, the critics add, slavery would have ended without a Civil War. Third, argue the critics, Lincoln subverted the free market with his mercantilist policies, thereby laying the groundwork for the big-government Progressives to follow. Fourth, Lincoln supposedly prosecuted the war tyrannically; in DiLorenzo’s absurd hyperbole, Lincoln was a “totalitarian” who constructed an “omnipotent” state.7 Let us look at each of these criticisms in greater detail—and put them to rest—starting with the claim that Lincoln spurned the fundamental principles of the founding by opposing secession.

The “Right” of Secession

To determine whether Lincoln advanced or undermined the basic principles of America’s founding, we must first understand what those principles are. According to DiLorenzo, the American Revolution was fundamentally about the secession and self-determination of “sovereign states”; “In the eyes of the American founding fathers, the most fundamental principle of political philosophy was the right of secession”;8 and the “right” of the states to secede was “self-evident to everyone at the time.”9 In his view, the states retained a “right” to secede at will from the Union, regardless of how heinous their reasons. Following DiLorenzo’s lead, Williams writes that the Civil War “laid to rest the great principle enunciated in the Declaration of Independence that ‘Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.’”10 On its own terms, Williams’s statement appears to be a damning critique of Lincoln, who often spoke of and invoked the Declaration of Independence.

What do the facts of history reveal about such claims?

To characterize the essence of the Revolution as “the right of secession” is ludicrous. The American Revolution encompassed years of colonial protests and imperial punishments, erupting in war in April 1775. Following months of open hostilities, the colonists transformed their cause into a revolutionary conflict for the independence of a new republic. The Declaration of Independence adopted by that new people and submitted to a candid world did not invoke secession as a fundamental political principle; it invoked the natural right of revolution, to alter or abolish a government that has become destructive of the ends for which it was created—to secure unalienable individual rights.

Beyond looking to the text of the Declaration, we can examine how the founders addressed the issue of secession when it actually arose. To fully understand the founders’ views on secession, we must also understand their views on state nullification of federal law. By reviewing the historical evidence, we shall see that, when Lincoln condemned secession as “the essence of anarchy,”11 he echoed rather than defied the founders.

The doctrine of states’ rights to secession is built on a faulty premise that is antithetical to American political theory. The premise is that the states created the federal government and can withdraw at will; that state governments are the constituents in the American polity that are sovereign; that states, as such, have rights. But in American political theory—at least since the constitutional reformation of 1787—not the states but the people are sovereign; only individuals have rights. This proposition is not simply reliant on Gouverneur Morris’s language in the preamble of the Constitution—language that, at Virginia’s ratifying convention, Patrick Henry unsuccessfully tarred as dangerous on the grounds that it changed the nature of the American government. James Madison in Federalist Paper 46 responded directly to the anti-Federalists who found Henry’s worries compelling, explaining where precisely sovereignty resides in the American republic:

The federal and State governments are in fact but different agents and trustees of the people, constituted with different powers and designed for different purposes. The adversaries of the Constitution seem to have lost sight of the people altogether in their reasonings on this subject; and to have viewed these different establishments not only as mutual rivals and enemies, but as uncontrolled by any common superior in their efforts to usurp the authorities of each other. These gentlemen must here be reminded of their error. They must be told that the ultimate authority, wherever the derivative may be found, resides in the people alone, and that it will not depend merely on the comparative ambition or address of the different governments whether either, or which of them, will be able to enlarge its sphere of jurisdiction at the expense of the other.12

Not one Federalist at the ratifying conventions made any claim that state secession would be some sort of check on the federal government. It would have been logical for them to make this argument if secession were so fundamentally important to them, especially in the face of anti-Federalist arguments that the states were being minimized and that the new federal government, which then had no Bill of Rights, was dangerous and too powerful. Yet they failed to appeal to this allegedly obvious trump card.13

Nor did Jefferson place more importance on secession in the years following his drafting of the Declaration, after the federal government had become entrenched. If Jefferson had considered the threat of secession a legitimate check on federal power, we should expect him to have appealed to it in 1798 and 1799, during what he called the “reign of witches,” when the Federalists were preparing for war with France by raising armies, passing taxes, and enacting the infamous Alien and Sedition Acts. Instead, Jefferson explicitly considered secession and firmly rejected it:

Perhaps this party division is necessary to induce each to watch & delate to the people the proceedings of the other. But if on a temporary superiority of the one party, the other is to resort to a scission of the Union, no federal government can ever exist. If to rid ourselves of the present rule of Massachusets & Connecticut we break the Union, will the evil stop there? Suppose the N. England States alone cut off, will our natures be changed? are we not men still to the south of that, & with all the passions of men? Immediately we shall see a Pennsylvania & a Virginia party arise in the residuary confederacy, and the public mind will be distracted with the same party spirit. What a game, too, will the one party have in their hands by eternally threatening the other that unless they do so & so, they will join their Northern neighbors. If we reduce our Union to Virginia & N. Carolina, immediately the conflict will be established between the representatives of these two States, and they will end by breaking into their simple units. Seeing, therefore, that an association of men who will not quarrel with one another is a thing which never yet existed, from the greatest confederacy of nations down to a town meeting or a vestry, seeing that we must have somebody to quarrel with, I had rather keep our New England associates for that purpose than to see our bickerings transferred to others. . . . But who can say what would be the evils of a scission, and when & where they would end? Better keep together as we are.14

Later, when a few New Englanders talked about secession, briefly, during the War of 1812, Jefferson declared, “A barrel of tar to each state South of the Potomac will keep all in order, and that will be freely contributed without troubling government. To the North they will give you more trouble. You may there have to apply the rougher drastics of Govr. Wright, hemp [rope] and confiscation.”15 This last was in reference to Robert Wright’s militia campaign against Maryland loyalists during the Revolutionary War—and it involved the use of execution and expropriation.16 Jefferson’s words hardly give comfort to modern writers who claim Jefferson’s legacy when promoting secession as the core American political ideal.

The overarching attitude toward secession remained negative in the decades following the founding. The next period in which Americans seriously debated secession was during the nullification crisis under the administration of Andrew Jackson. The confrontation was ostensibly over an egregious tariff law that Jackson’s allies had accidentally passed in a misguided attempt to play legislative chicken in an election year.17 South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun used southern outrage over the tariff—the region was emerging from a period of economic depression and relied heavily on imports—to expound a theory of state nullification of national laws. It was a novel idea obviously meant to address the increasing political power of the burgeoning population of the North—a power that could one day be deployed against slavery. Andrew Jackson’s response to nullification—and to the threat of secession it implied—was unequivocal. Neither was legal, both would lead to civil war, and, if necessary, he would meet the crisis in the field with the army. Jackson’s response was rooted neither in hubris nor in personal pique against his rival Calhoun, but in the wisdom of Madison himself, who was still alive in the early 1830s. Alarmed that advocates of nullification cited him and Jefferson as authorities, Madison spent great energy in his final days writing letters, public and private, reminding his forgetful countrymen of their unique constitutional order and of the inestimable value of the Union.18 The octogenarian Madison warned, “Nullification has the effect of putting powder under the Constitution & Union, and a match in the hand of every party, to blow them up at pleasure.”19

Political leaders in South Carolina unsuccessfully appealed to leaders in other states to endorse state nullification of federal authority. At least seventeen states responded to a South Carolina nullification ordinance; none of them endorsed nullification as a constitutional method of protesting or altering federal law. The Virginia legislature adopted the most favorable resolutions, declaring “the doctrines of State Sovereignty and State Rights . . . as a true interpretation of the Constitution of the United States.” But even Virginia could not rationalize nullification on those grounds; the legislature declared it could not sanction “the proceedings of South Carolina.”

The rest of the state legislatures were far more critical of the “rash and revolutionary measures” of South Carolina: Maine considered nullification as “tending directly to civil commotion, disunion, and anarchy.” Massachusetts thought that the doctrine would, “in practice,” tend “to the subversion of public tranquility, and the complete overthrow of the Government.” New York held that nullification was “wholly unauthorized by the Constitution of the United States, and in its tendency subversive of the Union and the Government thereof.” North Carolina’s statehouse was unsympathetic, calling nullification “revolutionary in its character, subversive of the Constitution of the United States and lead[ing] to a dissolution of the Union.” Ohioans called the ramifications of the doctrine “the most disastrous, and ruinous to the peace, prosperity and happiness of our common country.” Legislators in Indiana scoffed at nullification’s “impracticability, absurdity, and treasonable tendency.” Alabama expected war to ensue if South Carolina persisted in nullification, “which may lead to bloodshed and disunion, and will certainly end in anarchy and civil discord.” Mississippi added to the chorus: “We regard it as a heresy, fatal to the existence of the Union.” Connecticut pointed out that “no State has power to nullify, or the right to resist the execution of the same.” And Maryland declared that “this State does not recognize the power in any State, to nullify a law of Congress, nor to secede from the Union.” At least six states (Illinois, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Tennessee, and Maryland) warned South Carolina in no uncertain terms of their willingness to fight should the crisis be pushed that far: “But should our fellow citizens of South Carolina, contrary to our reasonable expectations, unsheath the sword, it becomes our solemn and imperative duty to declare, that no separate nation ought or can be suffered to intrude into the very centre of our Territory.”20 Obviously, such remarks flatly contradict DiLorenzo’s thesis that American liberty was rooted fundamentally in the “right” of secession.

In 1860, the Democratic president of the United States—James Buchanan—told the nation that secession “is wholly inconsistent with the history as well as the character of the federal Constitution.” He continued, “The truth is, that it was not until many years after the origin of the federal government that such a proposition was first advanced. It was then met and refuted by the conclusive arguments of General Jackson.”21 The very same Andrew Jackson called secession a “revolutionary act” and declared, “Disunion by armed force is treason.”22

A vast and long history—spanning from Jefferson’s prediction that secession would beget secession to Jackson’s nullification proclamation—undergirded what Lincoln said in his first inaugural address. DiLorenzo’s pretense that the founders or their intellectual heirs would have supported secession—especially secession for the primary purpose of constructing a government devoted to institutionalizing human bondage—is both absurd and shameful.

Lincoln Versus the Confederates on Slavery

Let us now turn to the claim that Lincoln did not truly care about ending slavery, that he invoked that cause merely as a pretext to expand federal power.

In his foreword to DiLorenzo’s 2002 book, Williams characterizes Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation as “little more than a political gimmick” and charges that Lincoln actually supported slavery.23 What, then, was Lincoln’s “real” motive for pursuing the Civil War? According to Williams, Lincoln opposed secession mainly to maintain tariffs on the South: “During the 1850s, tariffs amounted to 90 percent of federal revenue. Southern ports paid 75 percent of tariffs in 1859. What ‘responsible’ politician would let that much revenue go?”24

To “prove” that Lincoln cared primarily about Whig “mercantilism,” not slavery, DiLorenzo observes that “Lincoln barely mentioned slavery before 1854.”25 Of course, this could be said of everyone except the abolitionists. Whigs and Democrats were national party coalitions that largely debated the big issues of domestic political economy—the tariff, the bank, and internal improvements. Slavery was a sectional issue that divided North and South and splintered the national parties. Democrats and Whigs knew the issue was a hornets’ nest and studiously avoided poking it. DiLorenzo ignores the reason why Lincoln changed his tune after 1854—a pivotal year for Lincoln, as it brought him out of his political retirement (he had served in Congress from 1847 to 1849). What is that reason?

In 1854, Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, engineered by Lincoln’s archrival Stephen A. Douglas on the pretext of “popular sovereignty.” The measure overturned the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and permitted white settlers to determine by vote whether to allow human bondage in the territories. David M. Potter, one of the great historians of the last century, correctly said of the act that few “events have swung American history away from its charted course so suddenly or so sharply.”26

To the degree that Lincoln was silent about slavery prior to 1854, it was because he (too complacently) thought slavery had been contained and might be on a path to extinction. As Lincoln properly recognized, the notion that majority will could alienate an individual’s rights—could turn men into the property of other men—was antithetical to the essential principles of the founding. What spurred him into eloquence and action was the horrifying realization that many of his fellow Americans might no longer believe that to be true.

Douglas’s legislation led to the implosion of the Whig Party, whose southern members could no longer openly associate with their antislavery northern colleagues and hope to win elections in the South. Lincoln reentered politics and eventually joined the Republican Party, an organization made up of many former northern Whigs as well as former northern Democrats such as Hannibal Hamlin of Maine and Salmon P. Chase of Ohio.27 Lincoln’s chief goal was to restore the understanding and consensus that slavery was morally wrong and should not spread into the territories—and to thwart the career of the man who had upended this understanding: Stephen A. Douglas. From 1854 to 1860, Lincoln wrote privately and spoke publicly and widely to advocate his views. Those who claim that Lincoln’s “real” or primary agenda was something other than to stop the spread of slavery peddle falsehoods (if not willful deception).

From the first moment in 1854 when he had the chance to confront Douglas directly, as he did at a joint appearance in October at Peoria, Illinois, Lincoln hammered repeatedly on a consistent theme:

This declared indifference [Douglas claimed it did not matter to him which way popular sovereignty decided the status of slavery in Kansas], but as I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery, I can not but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites—causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty—criticising the Declaration of Independence. . . .28

A few years later, at the Cooper Institute in New York City, Lincoln—more worried than before because of the pernicious ideas contained in the Supreme Court’s 1857 decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford—reminded his countrymen, again, of the great principles that motivated the founders and the evil of compromising those principles:

Let us be diverted by none of those sophistical contrivances wherewith we are so industriously plied and belabored—contrivances such as groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong, vain as the search for a man who should be neither a living man nor a dead man—such as a policy of “don’t care” on a question about which all true men do care—such as Union appeals beseeching true Union men to yield to Disunionists, reversing the divine rule, and calling, not the sinners, but the righteous to repentance—such as invocations to Washington, imploring men to unsay what Washington said, and undo what Washington did.29

Even when, in 1860, Lincoln sought to convince his former congressional Whig colleague Alexander H. Stephens—the future vice president of the Confederacy—that the North would not interfere with slavery where it existed, he added, “I suppose, however, this does not meet the case. You think slavery is right and ought to be extended; while we think it is wrong and ought to be restricted. That I suppose is the rub. It certainly is the only substantial difference between us.”30

Lincoln knew that he, not Douglas and his cohorts, remained true to the founding vision regarding the question of slavery. Lincoln’s words echoed those of the founders: Washington freed his slaves (posthumously) and wrote, “I wish from my soul that the Legislature of [Virginia] could see the policy of a gradual Abolition of Slavery.”31 In his last public act, Franklin declared to Congress that slavery is “an atrocious debasement of human nature.”32 Jefferson (despite his holding of slaves and his voluminous private and public series of racist musings about African intellectual capacity) wrote in the Notes on the State of Virginia (1787), “The spirit of the master is abating, that of the slave rising from the dust, his condition mollifying, the way I hope preparing, under the auspices of heaven, for a total emancipation.”33 To Douglas and company, these words of the founders—and the principles behind them—were to be ignored or subverted.

Lincoln’s modern critics, of course, do not argue (with Douglas) that slavery should be allowed; rather, they claim that, absent the Civil War, slavery could have been abolished through peaceful compensation and that the Confederates, had they been allowed to dismember the republic, quickly would have ended slavery on their own. Such claims do not withstand scrutiny.

Begin with the claim that peaceful compensation might have ended slavery. The results of efforts to, in effect, buy off slaveholders during the Civil War show that an effort to have done so prior to the war almost certainly would have failed.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a military measure, the legitimacy of which flowed from the war and Lincoln’s role as commander in chief—and an idea developed in congressional debates in the 1830s by John Quincy Adams.34 This narrow legal ground is why it could hold legal effect only in the areas still under rebellion at the moment of its issuance. For the areas of the country under Union military control and for the slave states not in a state of insurrection, Lincoln had several options. The first was to do nothing, and, if he were a cynic who did not care about slavery, that is probably what he would have done. The second was to try to encourage a voluntary abolition of the institution by compensating owners and, Lincoln hoped, offering opportunity to the former slaves. Toward this end, Lincoln met with black leaders to present to them a plan that was also favored by Jefferson, Madison, and Henry Clay: to free the slaves and transport them to Africa or Haiti. This public meeting understandably went nowhere: The black Americans Lincoln invited informed the president that they would rather fight for their unalienable rights in their country.35 Lincoln simultaneously attempted to convince leaders of the border states—some of whom had long insisted that emancipation was unthinkable without colonization—to accept federal money to buy their slaves and set them free. The test case was tiny Delaware, inhabited by fewer than two thousand slaves—but Delaware’s legislature rejected the idea.36 If compensated emancipation could not work in a state with relatively few slaves, what hope did it have of working in Kentucky or Maryland, which, combined, had nearly three hundred thousand slaves?37

If compensated emancipation would not have worked, might the pro-slavery Confederates have voluntarily abandoned slavery in the years or decades after they instead fought a bloody war to preserve the institution? Although the question is not of much importance in evaluating Lincoln—he acted in response to the actual actions of the southern states at the time, not in response to the hypothetical actions of those states in the indefinite future—it is worth pondering. The answer is that the Confederate states most likely would not have voluntarily abandoned slavery.

Hereditary, race-based chattel slavery was never simply an economic institution. From the beginning, it necessitated a restructuring of the societies where it existed—legal and cultural institutions changed to deal with its consequences. Jefferson saw this influence as antirepublican and detrimental to everyone:

There must doubtless be an unhappy influence on the manners of our people produced by the existence of slavery among us. The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other.38

A half century later, South Carolinian John C. Calhoun—a man whom some of Lincoln’s critics uphold as a philosopher of liberty—asserted on the floor of the U.S. Senate that slavery “is, instead of an evil, a good—a positive good.” Calhoun also suggested that free institutions actually benefited from the existence of slavery in the South:

I fearlessly assert that the existing relation between the two races in the South, against which these blind fanatics are waging war, forms the most solid and durable foundation on which to rear free and stable political institutions. It is useless to disguise the fact. There is and always has been in an advanced stage of wealth and civilization, a conflict between labor and capital. The condition of society in the South exempts us from the disorders and dangers resulting from this conflict; and which explains why it is that the political condition of the slaveholding States has been so much more stable and quiet than that of the North.39

An important practical effect of this rejection of the Declaration’s

Enlightenment convictions was that Southerners became less devoted to union

and more devoted to slavery as a way of life. Southerners violated treaties by preventing free black sailors of other countries from “corrupting” Southern slaves and free blacks with news and ideas from abroad. At the behest of Southerners, Congress imposed a gag rule to instantly table abolitionist petitions. Southern political leaders censored speech and the press to curtail criticism of slavery. Postmasters general routinely allowed Southern authorities to confiscate “incendiary” publications. Acting on rumors of slave rebellions, white Southerners routinely pursued bloody campaigns of terror against slaves, injuring and slaughtering many. The South not only abandoned the Enlightenment ideals of the founding; it regressed into a closed society infused with tremendous paranoia.40

Pro-slavery Southerners—by DiLorenzo’s reckoning the champions of local sovereignty—made no reference to such sovereignty when they advocated aggressive federal enforcement of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law in reluctant Northern communities sympathetic to people running for their liberty. Northern Whigs and Democrats happily obliged these calls for federal legal supremacy in the 1850s despite massive Northern protest.41 For his part, Lincoln repeatedly assured Southerners that he took his obligations to enforce such laws, although personally distressing, to be a sacred obligation: “[A]ll the protection which, consistently with the Constitution and the laws, can be given, will be cheerfully given to all the States when lawfully demanded, for whatever cause—as cheerfully to one section, as to another.”42

If Confederates were on the verge of realizing that slavery was an economic albatross that they would willingly abandon in two decades, as Mencken suggested they would, they had an odd way of displaying their impending Enlightenment.43 Far from denying Lincoln’s damning charge that they thought slavery was right, they embraced it. When William L. Harris, secession commissioner from Mississippi, made his appeal to the Georgia Assembly, he did so in the most revealingly repugnant way possible: “Our fathers made this a government for the white man, rejecting the negro, as an ignorant, inferior, barbarian race, incapable of self-government, and not, therefore, entitled to be associated with the white man upon terms of civil, political, or social equality.”44 South Carolina, in a statement that today scarcely seems possible, explained its reasons for secession:

[The non-slaveholding states] have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery; they have permitted the open establishment among them of societies, whose avowed object is to disturb the peace and to eloign the property of the citizens of other States. They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes; and those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection.45

Lincoln’s old friend, the southern Whig Alexander Stephens, as the Confederate vice president, plainly said that when the founders argued that slavery “was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically,” they had been “fundamentally wrong.” “Our new government,” Stephens told an audience at the Savannah Atheneum, “is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.”46

Lincoln held that slavery was a moral evil; the Confederates held that it was a moral good. Lincoln prosecuted the Civil War mainly to prevent secession in the name of human bondage; the Confederates fought the war mainly to preserve slavery. The pro-slavery “intellectuals” of the South were prepared neither for compensated emancipation nor for the expeditious phasing out of slavery for economic reasons—the claims of Lincoln’s modern critics notwithstanding. Morally, Lincoln was in the right, and his Confederate enemies were in the wrong—judged by the standards set forth in the Declaration of Independence.

Although the foregoing demonstrates that Lincoln prosecuted the Civil War primarily because of slavery, what are we to make of Lincoln’s economic policies, their role in the war, and their lasting impacts on American politics? We turn next to such questions.

Lincoln’s Economic Policies in Context

Unsurprisingly, after the New Deal and Great Society fundamentally altered the relationship of the state to the individual and brought expansive federal controls into economic life, many people searched for the antecedents of that transformation. Rather than look to ideas as the fundamental cause of this change (specifically, the rise of socialist and Progressive ideas), Rothbard and his libertarian cohorts blamed the Civil War.

According to the fantasy spun by Rothbard, DiLorenzo, and company, Lincoln prosecuted the Civil War mainly to institute his expansionist vision of the federal government. According to this fantasy, Lincoln broke with America’s free-market past and laid the groundwork for the regulatory-entitlement state to follow. The reality is that, although Lincoln promoted a variety of policies ultimately incompatible with a free market, his policies were substantially similar to policies promoted by the founders, and they were substantially different from the policies promoted by Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Lyndon Baines Johnson, and the like. Let us look at relevant aspects of America’s history to put Lincoln’s actions and policies in context.

According to DiLorenzo, the fount of centralized government power is Alexander Hamilton, whom he sees as the political and economic mentor of Henry Clay. Lincoln admired Clay immensely and was a devotee of the Kentuckian’s legislative program known as “the American System.” This program called for the federal government to support the creation of an integrated and national marketplace, to fund national internal improvement projects (roads, canals, etc.), to charter a national bank, to protect vital American manufacturing industries with tariffs, and to prevent the states from interfering with national and international trade. According to DiLorenzo, “Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson, Tyler, and others consistently made constitutional arguments in opposition” to such “mercantilist policies.” Lincoln (DiLorenzo’s story continues) supposedly “seethed in frustration” over these rebuffs, biding his time and waiting for his opportunity—the Civil War as it turned out—to implement Clay’s policies and set the republic on its course, inexorably, to the Sedition Act of 1918, to the National Industrial Recovery Act, to the Patriot Act, to Obamacare.47

For DiLorenzo to claim that Lincoln opposed founding principles because he substantially agreed with Alexander Hamilton on economic matters is curious, to put it mildly. Hamilton, whatever his flaws, is one of the key founders of America’s constitutional order. Hamilton dropped out of King’s College (Columbia) to fight for American independence, served for years as General Washington’s chief adjutant and aide-de-camp, served in the Continental Congress, helped to write and ratify the Constitution, and then entered Washington’s cabinet as the country’s first treasury secretary.

It was during his time at treasury, by DiLorenzo’s account, that Hamilton showed his true, un-American colors. But DiLorenzo’s reading of the historical record is lazy and clumsy. Hamilton’s formative experience as a young man was the eight-year war for independence—particularly from the point of view of the Continental Army. He witnessed eight years of disunity of purpose, the inability of the Continental Congress to adequately fund the army and navy, and the countless ways that the centrifugal tendencies of the new union under the Articles of Confederation (drafted in 1777 and ratified in 1781) hampered the ability of Americans to break free of the British Empire. The political picture appeared little rosier to Hamilton during peace in the 1780s. The states—including his own state of New York—violated the peace treaty with the British and could not be brought in line by a weak and broke national government. That same government could not expel the British from northwestern forts within the boundaries of the United States, could not stop Barbary privateers from attacking American merchants in the Mediterranean and taking American sailors hostage, could not punish the Spanish for closing the port of New Orleans, could not raise an army to protect settlers from Indian attack, and could not pay the debts incurred by the Revolutionary War. A government incapable of accomplishing such basic tasks, Hamilton believed, could hardly hope to succeed in its broader purpose of upholding individual rights.

All of Hamilton’s suggestions as treasury secretary were meant to make the republic powerful enough to protect itself in an exceedingly dangerous world.48 Compiling all the debts of the Revolution under the new federal government—and successfully financing it—would mean an enhanced credit and reputation at home and abroad. A federally chartered national bank would offer “important aid” in “dangerous and distressing emergencies,” as smaller but similar “public banks” had “in some of the most critical conjunctures of the late war.” And government support for America’s manufacturing sector, now detached from Britain’s mercantilist empire, would prevent a recurrence of the “extreme embarrassments of the United States during the late War, from an incapacity of supplying themselves.”49 Calling Hamilton a “mercantilist,” as DiLorenzo does because of these policy prescriptions for the serious problems facing the republic, is like calling Adam Smith a Marxist because he believed value was derived from labor. DiLorenzo’s attack on Hamilton also indicts everyone who supported Hamilton’s proposals, including George Washington, John Adams, John Marshall, Henry Knox, and numerous other honored heroes of America’s founding.

Henry Clay is an even more peculiar target in the revisionist campaign against Lincoln. Clay was no supporter of Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists; he was a Jeffersonian through and through. He was a key supporter of President Madison before and during the War of 1812; speaker of the Jeffersonian-dominated House of Representatives for more than a decade; and a devoted Union man who dissolved the Missouri Crisis in a compromise that allowed Missouri into the country as a slave state but prohibited the institution in almost the entirety of the remaining Louisiana Purchase. Like James Madison, John Marshall, John Quincy Adams, and numerous others, Clay saw an ineffective federal government as the cause of the problems the country experienced during the War of 1812 and a threat to national peace in the aftermath of the Missouri Compromise. His response was to actively counteract the centrifugal tendencies of the sprawling and diverse “extended republic” through the agency of the only national institution that existed—the federal government. The disintegration of the republic was not an attractive idea to Clay or other nationalists—as it likely meant the creation of a European-style, balance-of-power system among the states, along with the perpetual taxation and standing armies that went with it.50

Clay’s own sobering war experience—the War of 1812—surely informed his appeals in Congress to embrace road and canal construction:

Is there not a direct and intimate relation between the power to make war, and military roads and canals? . . . We have recently had a war raging on all the four quarters of the union. . . . I do not desire to see military roads established for the purpose of conquest, but of defence; and as a part of that preparation which should be made in a season of peace for a season of war. . . . No man, who has paid the least attention to the operations of modern war, can have failed to remark, how essential good roads and canals are to the success of those operations.51

Clay also appealed to national defense regarding the protective tariff at the heart of his plan to create a vital and integrated home marketplace:

Its importance, in connection with the general defence in time of war, cannot fail to be duly estimated. Need I recall to our painful recollections the sufferings, for the want of an adequate supply of absolute necessaries, to which the defenders of their country’s rights and our entire population, were subjected during the late war?52

Although James Madison vetoed Clay’s initial attempts to promote “internal improvements,” Madison—himself disturbed by the harrowing experience of the second war with Britain—also fought to establish the Second Bank of the United States and the first truly protective tariff in American history, both of which passed into law under his signature in 1816.

While DiLorenzo and others pretend that Hamilton’s “mercantilism” clashed with the practices of other founders, such critics fail to account for why the Jeffersonians in power, from Albert Gallatin and James Madison to Thomas Jefferson himself, adopted nearly all of Hamilton’s suggestions for how to protect the republic in a dangerous and war-torn world dominated by powerful empires hostile to the United States. In fact, it was Hamilton’s great political foe, Jefferson, who used the federal government in peacetime to impose autarky on the American marketplace and who employed the army and navy of the United States in domestic law enforcement because local and state authorities were incapable of enforcing his regionally unpopular Embargo Act of 1807. Jefferson’s treasury secretary, Albert Gallatin, warned his chief what their yearlong experiment meant: embracing powers that were “arbitrary,” “dangerous,” and “odious.”53 Few more-sweeping exercises of government power were ever employed in the 19th century.54

Regarding Clay, there is no doubt that Lincoln followed him. Clay was, as Lincoln proudly admitted, “my beau ideal of a statesman, the man for whom I fought all my humble life.”55 But hundreds of thousands of other Americans

also identified with “Harry of the West” (as many called Clay) and with the

anti-Andrew Jackson Whig Party.

The point of all of this is not to defend the (limited) interventionist policies of the early federal government. Rather, the point is to show that Lincoln’s views and policies were consistent with those of many founders. The charge against Lincoln that, in his economic policies, he somehow broke with the founders and prepared the way for FDR and the like is a fantastic misrepresentation of history.

We must judge the economic policies of Lincoln and the founders in their historical context. Questions of political economy were not so clearly delineated, nor as well understood, then as now. Lincoln’s writings on these issues—matters at the heart of the debate between the Jacksonian Democrats and the Whigs of America’s second party system—are not among his finest or most enduring compositions. They betray the same fallacies of economic reasoning that bedeviled many intellectuals in the Western world at that time—but they hardly mean Lincoln was basically an antiliberal progenitor of a “totalitarian” state. (Notably, many Southerners—including Southern Whigs—happily supported the sort of economic policies Lincoln favored; such policies are not what drove them to secession.)

In important ways, Lincoln was a better spokesman for an open marketplace than was Jefferson, who elevated the agrarian life above all others. Lincoln’s Whigs and later Republicans (the latter taking their name from Jefferson’s earlier party, which had since morphed into Jackson’s Democrats) may have been “snobs and elitists, the moralists and the do-gooders” (in the words of Rich Lowry), but they made clear their vision for the republic was open to everyone, including urban workers.56 Whereas Jefferson regarded working for others, especially in cities for wages, as a sign of lost independence, Lincoln regarded such work as perfectly legitimate and as a means to improve one’s life—including his own.

I am not ashamed to confess that twenty five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat—just what might happen to any poor man’s son! I want every man to have the chance—and I believe a black man is entitled to it—in which he can better his condition—when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him! That is the true system.57

The (classical) liberal consensus for laissez-faire and free trade lay much further ahead in the 19th century. All American statesmen, Hamilton and Clay included, claimed free trade was the ideal to which they should aim. Even so, almost everyone held that opening America to fully free trade while Britain, France, and others continued with mercantilism would place the United States and its enterprising businessmen at a severe disadvantage. Although the fallacies of that argument may be clear today to those of us who have benefited from the work of political economists little known or understood during the antebellum period (e.g., Jean-Baptiste Say, David Ricardo, Frédéric Bastiat, and Carl Menger), such fallacies were not generally recognized by statesmen of earlier eras.

We may bemoan the fact that free-market ideas did not come earlier or more clearly to men such as Hamilton, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Gallatin, and Clay—but their “failure” in economic matters hardly compares to the failures of many Americans regarding another crucially important issue. Many American political leaders, both in the time of the founders and in the time of Lincoln, utterly failed to come to grips with what all reflective men knew to be a great moral evil and something that flatly contradicted the American principles of liberty and self-government: slavery.

Slavery, not economic policy, is the fundamental issue on which Lincoln’s legacy rests; and, on that issue, Lincoln was essentially right, whereas his Confederate enemies were horrifically wrong.

The final task before us is to evaluate the manner in which Lincoln prosecuted the Civil War.

Lincoln’s War Actions in Context

The last peg in the assault on Lincoln involves Lincoln’s handling of the war itself. One can agree that Lincoln understood and respected America’s founding principles, properly condemned the pro-slavery secession movement, and genuinely cared about the injustice of slavery and its potential spread, yet reasonably criticize Lincoln’s handling of the war.

During the Civil War, the federal government engaged in and oversaw conscription; income taxes; a resurrection of centralized government finance and banking; the emission of paper money; the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus; military arrests, trials, and imprisonments; temporary nationalizations; mass wealth confiscations; government closing of newspapers; and declarations of martial law. Surely, these measures are cause for alarm.

Not long after Lincoln’s assassination, the Supreme Court rebuked Lincoln for invoking the wartime emergency in support of his actions:

The Constitution of the United States is a law for rulers and people, equally in war and in peace, and covers with the shield of its protection all classes of men, at all times and under all circumstances. No doctrine involving more pernicious consequences was ever invented by the wit of man than that any of its provisions can be suspended during any of the great exigencies of government. Such a doctrine leads directly to anarchy or despotism, but the theory of necessity on which it is based is false, for the government, within the Constitution, has all the powers granted to it which are necessary to preserve its existence, as has been happily proved by the result of the great effort to throw off its just authority.58

Yet in these matters, too, Lincoln deserves to be judged in the light of historical context. Few presidents have been confronted with disasters and emergencies during their times in office as monumental as those Lincoln faced. Fewer still have reacted to such crises as conscientiously as Lincoln did when the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter in April 1861.59

There is little question that the Confederate attack on a federal military installation required a response. Lincoln immediately issued a call for volunteers in the same language and form used by George Washington when he confronted the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. But Lincoln’s limited action of calling for volunteers, for seventy-five thousand three-month soldiers to put down the rebellion in South Carolina, prompted Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Arkansas to join the rebels. Then Lincoln’s immediate crisis became holding on to the remaining slave border states—Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. Nearly all the suspensions of habeas corpus, arrests, newspaper closings, and the like occurred in these states—where local skirmishes between Union and Confederate factions dominated the first year or two of the war on the border.60 “I think to lose Kentucky,” Lincoln wrote to an ally, “is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor, as I think, Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us.”61

Ponder the moment in 1861 when Virginia was lost: The capital of the country shared a border with rebel-held territory; in Baltimore, pro-Confederate mobs attacked the soldiers responding to Lincoln’s call for volunteers; Confederate sympathizers sabotaged bridges and telegraph lines leading into Washington; and Congress was out of session until July. The only part of the government capable of action in this emergency of emergencies was the executive branch.

In a comparable moment, with a British army moving north to cut off American access to one of the country’s most important ports, Andrew Jackson had imposed military law on the people of New Orleans, made “arbitrary” arrests, ignored a judge’s rulings countermanding him, and eventually ordered the arrest of the judge. After he defeated the British and ended the crisis, Jackson was fined for his actions—he paid the fine, and Congress subsequently refunded it.62 Lincoln was well aware of Jackson’s actions and pointed out that they imposed no lingering harms:

It may be remarked: First, that we had the same Constitution then as now; secondly, that we then had a case of invasion, and now we have a case of rebellion; and, thirdly, that the permanent right of the People to Public Discussion, the Liberty of Speech and the Press, the Trial by Jury, the Law of Evidence, and the Habeas Corpus, suffered no detriment whatever by that conduct of Gen. Jackson, or its subsequent approval by the American Congress.63

Lincoln reasonably thought of his wartime actions as consonant with those of previous leaders. When a delegation from Baltimore pleaded with Lincoln to compromise in April 1861, he replied sternly: “[Y]ou would have me break my oath and surrender the Government without a blow. There is no Washington in that—no Jackson in that—no manhood nor honor in that.”64 Lincoln was aware of the ways previous presidents from George Washington to Andrew Jackson to Zachary Taylor had handled crises, and that awareness informed his own actions.

What of the civilian arrests? During the first ten months of the war, Secretary of State William H. Seward of New York handled the internal security of the Union and oversaw 864 civilian arrests. Historian Mark E. Neely Jr. conducted the most extensive research to date of the numbers of arrests during the Civil War and the identities of the prisoners. He finds that some 85 percent of those arrested under Seward were from the Confederacy, the border states, the District of Columbia, or a foreign country—people from or very near Confederate-controlled parts of the country. Neely concludes that the military justice system—particularly in a war-ravaged border state such as Missouri—was a civil liberties nightmare. But most of the fourteen thousand or so total civilian arrests during the Civil War were “caused by the mere incidents or friction of war, which produced refugees, informers, guides, Confederate defectors, carriers of contraband goods, and other such persons as came between or in the wake of large armies.”65 The government’s actions toward these Americans—a great many of whom aided the rebellion—do not necessarily offer a good precedent for others to follow; however, they fall far short of the horrors American slaves faced in the Confederacy or that Union soldiers faced as they starved in abominations such as the Andersonville prison camp.66

Next, consider conscription. If we criticize Lincoln for imposing a wartime draft, then we must also criticize the Confederacy on the same grounds, as it beat Lincoln to the punch by more than a year. In April 1862, the Confederates “enacted the first conscription law in American history” and boosted their manpower in the campaigns of that year by about two hundred thousand men, as James McPherson reports. The Union resisted following suit for more than a year, and the law it eventually passed was “a clumsy carrot and stick device to stimulate volunteering”; only 7 percent of the people called up were ever actually pressed into service.67

Although the federal government had been unblemished by conscription up to this point, state governments sometimes pressed their militias into service during the Revolution and the War of 1812. Had the War of 1812 dragged into 1815, there is almost no doubt the Madison administration would have secured a conscription act already put before Congress by Secretary of State and War James Monroe.68 Importantly, Lincoln’s conscription was a wartime emergency measure, not a permanent institution; conscription did not reemerge until Woodrow Wilson steered the republic into World War I. Although such history does not justify Lincoln’s conscription, it does provide important context in judging it.

As for financing the war effort, the two sides engaged in all the usual ways of financing a titanic struggle:

Unlike the Confederacy, which relied on loans for less than two-fifths of its war finances, the Union raised two-thirds of its revenues by this means. And while the South ultimately obtained only 5 or 6 percent of its funds by actual taxation, the northern government raised 21 percent in this manner.69

Lincoln saw the income tax—3 percent on all annual incomes over $800—as a wartime expedient; he never spoke of it as anything else. In 1895, the Supreme Court declared the income tax unconstitutional, but the Civil War era income tax law had expired in the 1870s, as it was designed to do.

Both sides resorted to issuing inflationary paper currency. But whereas the Union’s use of greenbacks eventually caused a wartime inflation of 80 percent, the Confederacy’s reckless war finance policies and inflationary money printing caused an inflation of 9,000 percent.70

For DiLorenzo and others to assail Lincoln as some sort of Machiavellian tyrant who ruled as no one ever ruled before and who established the basis for an “omnipotent” state is absurd, especially considering that the Confederacy (except in its tariff schedule) imposed even more severe economic measures. General Ulysses S. Grant, a lifelong Democrat before the rebellion, was characteristically blunt in his assessment of the South at war: “The South had rebelled against the National government. It was not bound by any constitutional restrictions. The whole South was a military camp.”71

Whatever criticisms one might make of Lincoln’s prosecution of the war, they do not, by any reasonable standard, taint his broader legacy as the savior of the American republic and of the American ideal of equal liberty for all.

Conclusion

The Civil War was unlike every American war preceding it in scope, carnage, and bitterness. The fragile American nation risked following the example of a long line of republican experiments that had collapsed in internal tumult. Lincoln, whatever his faults, pursued the right overall course of action for the right reasons. Far from laying the foundation for the next century’s Progressives, he became one of history’s most inspirational champions of freedom and emancipation from bondage.

Faced with a rebellion fought to preserve slavery—the repugnant institution fundamentally at odds with the ideals of America’s founding—Lincoln sought to preserve the republic and its essential ideals.

Lincoln phrased the problems of republicanism and war in perhaps their most succinct and classic form when, at Gettysburg, he whittled down the problem to its core. Discussing the republic “conceived in liberty,” Lincoln said, “Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.”72 A central matter on Lincoln’s mind, as he told a crowd of well-wishers after his reelection, was the “grave question” of “whether any government, not too strong [to endanger] the liberties of its people, can be strong enough to maintain its own existence, in great emergencies.”73 Phillip Shaw Paludan observes, “Without the president’s devotion to and mastery of the political-constitutional institutions of his time, in all probability the Union would have lacked the capacity to focus its will and its resources on defeating [the] Confederacy.”74

Lincoln pointed out the relationship of his two great achievements—freeing the slaves and maintaining the freedom of the republic more broadly—in observing:

We know how to save the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it. We—even we here—hold the power, and bear the responsibility. In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free—honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best, hope of earth.75

Lincoln finally laid to rest the greatest contradiction of the republic’s founding as well as the great fear that republics were incapable of overcoming intestinal strife without ultimately sacrificing the liberties of the people. That legacy deserves posterity’s praise and admiration.

Despite the claims of Mencken, Rothbard, DiLorenzo, Williams, Paul, and others, the United States emerged from the Civil War with liberty not only intact, but enhanced. That achievement is due mostly to the caution, prudence, and principles of Abraham Lincoln, a man deeply impressed with the essential meaning of the founding and the revolutionary principles of Locke, Paine, and Jefferson.

As Lincoln fully realized, his conflict with Douglas was but an instance of a much broader struggle:

It is the eternal struggle between these two principles—right and wrong—throughout the world. They are the two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time; and will ever continue to struggle. The one is the common right of humanity and the other the divine right of kings. It is the same principle in whatever shape it develops itself. It is the same spirit that says, “You work and toil and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.” No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle.76

Those who tarnish the legacy of Lincoln—whether libertarian anarchists, Confederate apologists, or simply confused historians—do more than a grave injustice to this great man. They also, and consequently, aid and abet modern advocates of statism by enabling them to invoke Lincoln’s name in their efforts to promote political programs fundamentally at odds with the principles for which Lincoln fought.

If we care about historical truth and the “eternal struggle” for liberty, we must get Lincoln right—and we must speak up when others get him wrong.

You might also like

Endnotes

1. “List of Presidential Rankings: Historians Rank the 42 Men Who Have Held the Office,” Associated Press, February 16, 2009, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/29216774/.

2. Tim Russert, Meet the Press, NBC, December 23, 2007, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/22342301/ns/meet_the_press/t/meet-press-transcript-dec/.

3. H. L. Mencken, “Abraham Lincoln” (1922) and “The Calamity of Appomattox” (September 1930), A Mencken Chrestomathy: His Own Selection of His Choicest Writings (New York: Vintage, 1982), pp. 197–98, 223.

4. David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 241–42, 280–83; David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 15–16.

5. See, for example, Murray N. Rothbard, “H. L. Mencken: The Joyous Libertarian,” New Individualist Review, vol. 2, no. 2 (Summer 1962), pp. 15–27, reproduced at http://www.lewrockwell.com/1970/01/murray-n-rothbard/the-joyous-libertarian/.

6. Murray N. Rothbard, For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto, rev. ed. (San Francisco: Fox & Wilkes, 1978), p. 8.

7. Thomas J. DiLorenzo, Lincoln Unmasked: What You’re Not Supposed to Know About Dishonest Abe (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2006), pp. 149–60.

[groups_can capability="access_html"]

8. Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2002), 85.

9. DiLorenzo, Real Lincoln, pp. 90–91.

10. DiLorenzo, Real Lincoln, pp. xii–xiii.

11. Abraham Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address,” in Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher (New York: Library of America, 1989), p. 220.

12. James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, The Federalist Papers, ed. Isaac Kramnick (New York: Penguin, 1987), p. 297.

13. Akhil Reed Amar, America’s Constitution: A Biography (New York: Random House, 2005), pp. 29–39.

14. Thomas Jefferson, “Letter to John Taylor,” Philadelphia (June 4, 1798), in Writings, ed. Merrill D. Peterson (New York: Library of America, 1984), pp. 1049–50. Of course, Jefferson’s history on the topic of secession is complicated, to say the least. Later in the crisis over the Alien and Sedition Acts, he penned a draft of what became the Kentucky Resolutions that included phrasing eventually excised from the actual resolutions by the Kentucky legislature: “[E]very State has a natural right in cases not within the compact . . . to nullify of their own authority all assumptions of power by others within their limits: that without this right, they would be under the dominion, absolute and unlimited, of whosoever might exercise this right of judgment for them.” Jefferson spoke of the possibility of disunion during the Missouri Crisis, but he referred to that possibility as “deplorable” and a “prospect of evil.” Even in that situation, Jefferson hoped the whole affair might bring “the necessity of some plan of general emancipation & deportation [colonization] more home to the minds of our people than it has ever been before.” See Jefferson, “Draft of the Kentucky Resolutions,” (October 1798), and “Letter to Albert Gallatin,” Monticello (December 26, 1820), in Writings, pp. 453 and 1450; and Liberty and Order: The First American Party Struggle, ed. Lance Banning (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2004), pp. 233–43. Madison would later write that “allowances . . . ought to be made for a habit in Mr. Jefferson as in others of great genius of expressing in strong and round terms, impressions of the moment,” but, Madison added, Jefferson believed the general government had had the power to “coerce delinquent States” even under the old and much weaker Articles of Confederation. Madison further offered that it was “high time that the claim to secede at will should be put down by the public opinion.” See Madison, “Letter to Nicholas P. Trist,” Montpelier (May 1832), and “Letter to Nicholas P. Trist,” Montpelier (December 23, 1832), in Writings, ed. Jack N. Rakove (New York: Library of New York, 1999), pp. 860 and 862–63. As for how Jefferson dealt with the controversies over the Marshall Court’s nationalist opinions in the late 1810s and early 1820s, the Missouri Crisis, debates over “internal improvements” of the mid- and late-1820s, and the budding doctrine of “states rights,” see Dumas Malone, Jefferson and His Time, Volume Six: The Sage of Monticello (Norwalk: Easton Press, 1981), pp. 345–61 and 437–43; and William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), pp. 154–57.

15. Thomas Jefferson, “Letter to James Madison,” Monticello (June 29, 1812), in The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison 1776–1826, vol. 3, ed. James Morton Smith (New York: W. W. Norton, 1995), p. 1699.

16. Irving Brant, James Madison: Commander in Chief, 1812–1836 (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1961), pp. 24–25, 32.

17. Thomas L. Krannawitter, Vindicating Lincoln: Defending the Politics of Our Greatest President (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008), pp. 208–13.

18. Drew R. McCoy, The Last of the Fathers: James Madison and the Republican Legacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), pp. 119–170.

19. James Madison to Edward Coles (August 29, 1834), in The Writings of James Madison, vol. 9, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1910), p. 540.

20. All of these quotes can be found in State Papers on Nullification (Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, 1834) and are taken from Alexander V. Marriott, “It Has Long Been a Grave Question: The Republican War Dilemma in American History, 1776–1861” (Ph.D. dissertation, Clark University, 2013), pp. 439–41.

21. James Buchanan, “Fourth Annual Address” (December 3, 1860), The Works of James Buchanan, vol. 11: 1860–1868, ed. John Bassett Moore (New York: Antiquarian Press, 1960), p. 13.

22. Andrew Jackson, “Nullification Proclamation” (December 10, 1832), in Andrew Jackson vs. Henry Clay: Democracy and Development in Antebellum America, ed. Harry L. Watson (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1998), pp. 206–8.

23. DiLorenzo, Real Lincoln, p. x.

24. Walter E. Williams, “Abraham Lincoln,” Townhall.com, February 20, 2013, http://townhall.com/columnists/walterewilliams/2013/02/20/abraham-lincoln-n1513751/page/full.

25. DiLorenzo, Real Lincoln, pp. 54–55.

26. David M. Potter, The Impending Crisis: 1848–1861, completed and ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher (New York: Harper & Row, 1976), p. 167.

27. Jean H. Baker, Affairs of Party: The Political Culture of Northern Democrats in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (New York: Fordham University Press, 1998), pp. 52–63.

28. Abraham Lincoln, “Speech on Kansas-Nebraska Act,” Peoria, Illinois (October 16, 1854), in Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1832–1858, ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher (New York: Library of America, 1989), p. 315.

29. Lincoln, Address at Cooper Institute, New York City (February 27, 1860), in Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, p. 130.

30. Lincoln, “Letter to Alexander H. Stephens,” Springfield (December 22, 1860), in Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, p. 194.

31. George Washington, “Letter to Lawrence Lewis” (Mount Vernon, August 4, 1797), in Writings, ed. John H. Rhodehamel (New York: Library of America, 1997), p. 1002.

32. Benjamin Franklin, “An Address to the Public from the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage,” Philadelphia (November 9, 1789), in Benjamin Franklin: Writings, ed. J. A. Leo Lemay (New York: Library of America, 1987), p. 1154.

33. Thomas Jefferson, “Notes on the State of Virginia,” in Writings, p. 289. For the best discussion of Jefferson’s “central dilemma” of hating slavery while believing in black inferiority, see Winthrop D. Jordan’s magisterial White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968), pp. 429–81. There is no doubt that Jefferson’s “suspicion only” that blacks were naturally inferior to whites went much deeper than his pseudoscientific musings in the Notes. Regardless of the amount of ink Jefferson spilled calumniating Alexander Hamilton’s character and commitment to republican principles—and that has been spilled in the same cause by modern-day “neo-Jeffersonians” such as DiLorenzo—Hamilton had no such “dilemma,” and he was a central figure in the successful campaign to gradually abolish slavery in the state of New York. See Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (New York: Penguin, 2004), pp. 210–18, 580–81.

34. Daniel Farber, Lincoln’s Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), pp. 152–57.

35. Phillip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1994), pp. 130–35.

36. Krannawitter, Vindicating Lincoln, pp. 277–78.

37. Joseph C. G. Kennedy, Population of the United States in 1860; Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census, under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1864), pp. iv–xvii.

38. Jefferson, “Notes,” in Writings, p. 288.

39. John C. Calhoun, “Speech in the U.S. Senate, 1837,” in Defending Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Old South, A Brief History with Documents, ed. Paul Finkelman (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003), p. 59.

40. See David Robertson, Denmark Vesey: The Buried Story of America’s Largest Slave Rebellion and the Man Who Led It (New York: Vintage, 1999), pp. 111–23; “Letter from Virginia Governor John Floyd to South Carolina Governor James Hamilton, Jr.” (November 19, 1831), in The Confessions of Nat Turner and Related Documents, ed. Kenneth S. Greenberg (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1996), pp. 109–11; William Lee Miller, Arguing About Slavery: John Quincy Adams and the Great Battle in the United States Congress (New York: Vintage, 1995), pp. 115–49; James H. Dorman, “The Persistent Specter: Slave Rebellion in Territorial Louisiana,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 18, no. 4 (Fall 1977), pp. 389–404; Edwin A. Miles, “The Mississippi Slave Insurrection Scare of 1835,” Journal of Negro History, vol. 42, no. 1 (January 1957), pp. 48–60; Harvey Wish, “The Slave Insurrection Panic of 1856,” The Journal of Southern History, vol. 5, no. 2 (May 1939), pp. 206–22; and William W. White, “The Texas Slave Insurrection of 1860,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 52, no. 3 (January 1949), pp. 259–85.

41. See Michael F. Holt, The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 598–605; Paul Finkelman, Millard Fillmore (New York: Times Books, 2011), pp. 107–25; and Jean H. Baker, James Buchanan (New York: Times Books, 2004), pp. 83–94.

42. Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address,” Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, p. 216.

43. Mencken, “Calamity of Appomattox,” in Chrestomathy, p. 199.

44. “Address of William L. Harris to the Georgia General Assembly” (December 17, 1860), in Charles B. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001), p. 85.

45. “South Carolina Declaration of the Causes of Secession” (December 24, 1860), in The Civil War: The First Year Told by Those Who Lived It, ed. Brooks D. Simpson, Stephen W. Sears, and Aaron Sheehan-Dean (New York: Library of America, 2011), pp. 153–54.

46. Alexander H. Stephens, “Corner-Stone Speech” (March 21, 1861), in Civil War: The First Year, p. 226.

47. DiLorenzo, Real Lincoln, p. 234.

48. For more on this, see Karl-Friedrich Walling’s exceptional and brilliant study Republican Empire: Alexander Hamilton on War and Free Government (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1999).

49. Alexander Hamilton, “Report on a National Bank” (December 13, 1790); Alexander Hamilton: Writings, ed. Joanne B. Freeman (New York: Library of America, 2001), p. 576; and Hamilton, “Report on Manufactures” (December 5, 1791), in Writings, p. 692.

50. David C. Hendrickson, Union, Nation, or Empire: The American Debate over International Relations, 1789–1941 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009), pp. 132–39.

51. Henry Clay, “On Internal Improvement, in the House of Representatives” (March 13, 1818), in The Life and Speeches of the Hon. Henry Clay, vol. 1, ed. Daniel Mallory (New York: A. S. Barnes & Co., 1857), pp. 365–66.

52. Clay, “On American Industry, in the House of Representatives” (March 30 and 31, 1824), in Life and Speeches of Clay, p. 535.

53. Albert Gallatin, “Letter to Thomas Jefferson,” New York (July 29, 1808), in The Writings of Albert Gallatin, vol. 1, ed. Henry Adams (New York: Antiquarian Press, 1960), p. 398.

54. Forrest McDonald, The Presidency of Thomas Jefferson (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1976), pp. 139–59.

55. Abraham Lincoln, “First Lincoln-Douglas Debate,” Ottawa, Illinois (August 21, 1858), in Speeches and Writings, 1832–1858, p. 526.

56. Rich Lowry, Lincoln Unbound: How an Ambitious Young Railsplitter Saved the American Dream—and How We Can Do It Again (New York: Broadside Books, 2013), p. 64. See also Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln as a Man of Ideas (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009), p. 18.

57. Lowry, Lincoln Unbound, p. 116.

58. Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2 (1866).

59. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln as a Man of Ideas, pp. 119–20.

60. Albert D. Kirwan, John J. Crittenden: The Struggle for the Union (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1962), pp. 470–80.

61. Lincoln, “Letter to Orville H. Browning,” Washington, D.C. (September 22, 1861), in Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, p. 269.

62. J. C. A. Stagg, The War of 1812: Conflict for a Continent (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 152–54.

63. Lincoln, “Letter to Erastus Corning and Others,” Washington, D.C. (June 12, 1863), in Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, pp. 461–62.

64. Gerald J. Prokopowicz, “Military Fantasies,” in The Lincoln Enigma, ed. Gabor Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 64.

65. Mark E. Neely Jr., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), pp. 26–27, 233.

66. The Andersonville, Georgia, prisoner of war camp only was an atrocity because the Confederate government refused to treat captured Union soldiers who were black with the rights their uniforms demanded, subjecting them to beatings, summary executions, and reenslavement. See James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 791–802.

67. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, pp. 428–37, 600–611.

68. Stagg, War of 1812, pp. 134–38.

69. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 443.

70. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 447.

71. Ulysses S. Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters, ed. Mary Drake McFeely and William S. McFeely (New York: Library of America, 1990), p. 746.

72. Lincoln, “Address at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania” (November 19, 1863), in Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, p. 536.

73. Lincoln, “Response to Serenade,” Washington, D.C. (November 10, 1864), in Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, p. 641.