Religion vs. Free Speech

The Incompatibility of Faith and Freedom: Understanding the Threat to Free Speech

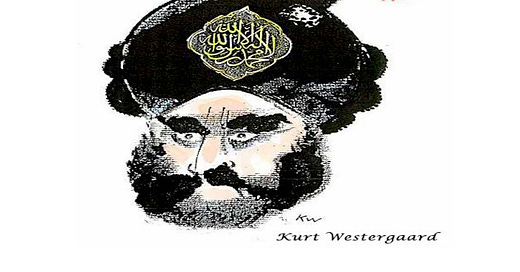

In the midst of the Cartoon Jihad, much has been said in defense of the right to free speech, especially by those on the religious right (such as Jeff Jacoby and Michelle Malkin). This effort is remarkable because, on the premises of religion, the Islamic militants are correct: There is no right to free speech.

Rights are principles specifying the kinds …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Objective Standard to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.