Editor’s note: This article is adapted from a live talk and has been lightly edited. It retains the cadence and idiosyncrasies of an oral presentation.

Many of us tend to think of fiction as primarily fun or entertaining. Good stories are fun, and we should enjoy them. However, we can also get other benefits from good stories that are less obvious but no less valuable. The people who create good stories look at the world and at others, and they observe things closely. When they create their stories, they condense what they’ve observed into characters, plotlines, and ideas that run throughout the work. All this contributes to making characters memorable and stories good. But some stories do even more than that. Some stories emphasize character arcs that are deliberately developed by the author for a specific, life-serving purpose. These are especially useful learning opportunities.

A character’s “arc” is the trajectory of the fundamental way in which he changes throughout the story. Many times, we think of this in terms of a good change. If you look up “character arc” on Google Images, you’ll get many different versions of diagrams with steps that look something like this: The protagonist starts off one way, encounters challenges, makes choices, undergoes change, and ends up significantly transformed for the better.[1] That is a positive character arc, but there are also negative character arcs; change does not necessarily have to be for the better. You could have a decay arc, for example. If you think about Anakin Skywalker in the Star Wars prequel trilogy—when he’s becoming Darth Vader—that’s a decay arc. There are also knowledge arcs in which the character is learning something throughout the course of the story; in Atlas Shrugged, Dagny Taggart goes through a knowledge arc. In other cases, the reader learns information throughout the story that recontextualizes the character or his actions in a significant way. In Harry Potter, Professor Snape is an example. He doesn’t significantly change throughout the story, but our view of him does as we learn more about him.

These are all valid types of character arcs. They all have their place in storytelling, but they’re not the kinds of arcs that I will focus on here. I will stick to the kind I first talked about: growth arcs. In a growth arc, a character needs to change to meet a challenge. It’s not just a change for no reason. This has some overlap with Joseph Campbell’s identification of a particular story structure that he dubbed the “hero’s journey,” but it’s not the same thing.[2] A hero’s journey includes the hero facing challenges and overcoming them, but he doesn’t necessarily have to change his fundamental essence to do so; the character may only need to gather certain knowledge or skills. We could think of Harry Potter—he doesn’t change fundamentally as a person. He is emotionally ready to fight Voldemort from the time he is eleven, which we can see at the end of the first movie. He acquires new skills and new knowledge, and he matures a little bit over the course of six years, but his fundamental values don’t change. He goes through a hero’s journey but not a growth character arc.

Why should we study growth character arcs? Why are they so valuable? To answer that, we first need to step back and ask, “What is the purpose of art? What does art do?” Fundamentally, art takes abstract ideas—such as love, courage, justice, or friendship—and concretizes them. To concretize an idea through fiction is to show its nature and consequences through a specific event or series of events—things we can see and/or hear. Done well, this creates a form of the abstraction that is vivid and memorable; we can think of a particular abstraction, and this representative character or story will hop into our minds. If we think about a character with a misguided idea of justice, we might think of Javier from Les Miserables. He and other lifelike, vivid characters are memorable because they show us strongly and clearly that certain ideas and values—if acted on—have certain consequences. No accidents or chance events interfere with the portrayal of ideas and their consequences in a good work of art.

This makes these characters valuable examples for thinking and communication as well as inspiration. As we’ll see, if a character is going through a growth arc, then he becomes an embodiment of the lesson that he learned through that arc. Specifically, in an integrated work of fiction, at least some of the main characters will have arcs that embody the theme of the work or an aspect of the theme. We’ll see how this works as we go through some examples. I’ll give you the theme of each story, and we’ll see what lessons the characters learn as well as how the lessons illustrate their respective themes.

The theme of Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged is “the crucial value of the human mind.” Everything in that book is intended to convey that theme. The book is more than a thousand pages; the story has a lot going on, and all of it is intended to illuminate, illustrate, or show some element of this theme.

Much of what I’m saying will apply to some extent to other forms of art as well. Movies, TV shows, video games, and (to a lesser extent) painting, sculpture, and many other art forms all have a theme. If we look at a work of art and identify its theme—if we try to say what this artwork shows us about the creator’s view of life (or even the universe as a whole)—then we can do a couple things. We can explore whether the artwork bears out its idea and presents it convincingly, and we can evaluate whether the work is life serving or not. Does the theme convey an idea that is good for human life—or bad for it? Here, we’ll focus on growth arcs found in books that have life-serving themes—books in which it’s easy to see how the lessons that the characters learn might help us improve our own lives.

If we study character arcs deliberately in this way, we can do at least two things: (a) We can learn or be reminded of the specific life-serving lessons that the characters are learning; and (b) if we step back and look at the structure of a character arc, we can start to create them in our own lives. We can look at people, situations, and challenges and say, “I’m going to make this part of my growth arc. I’m going to make this an opportunity to improve myself and my life.”

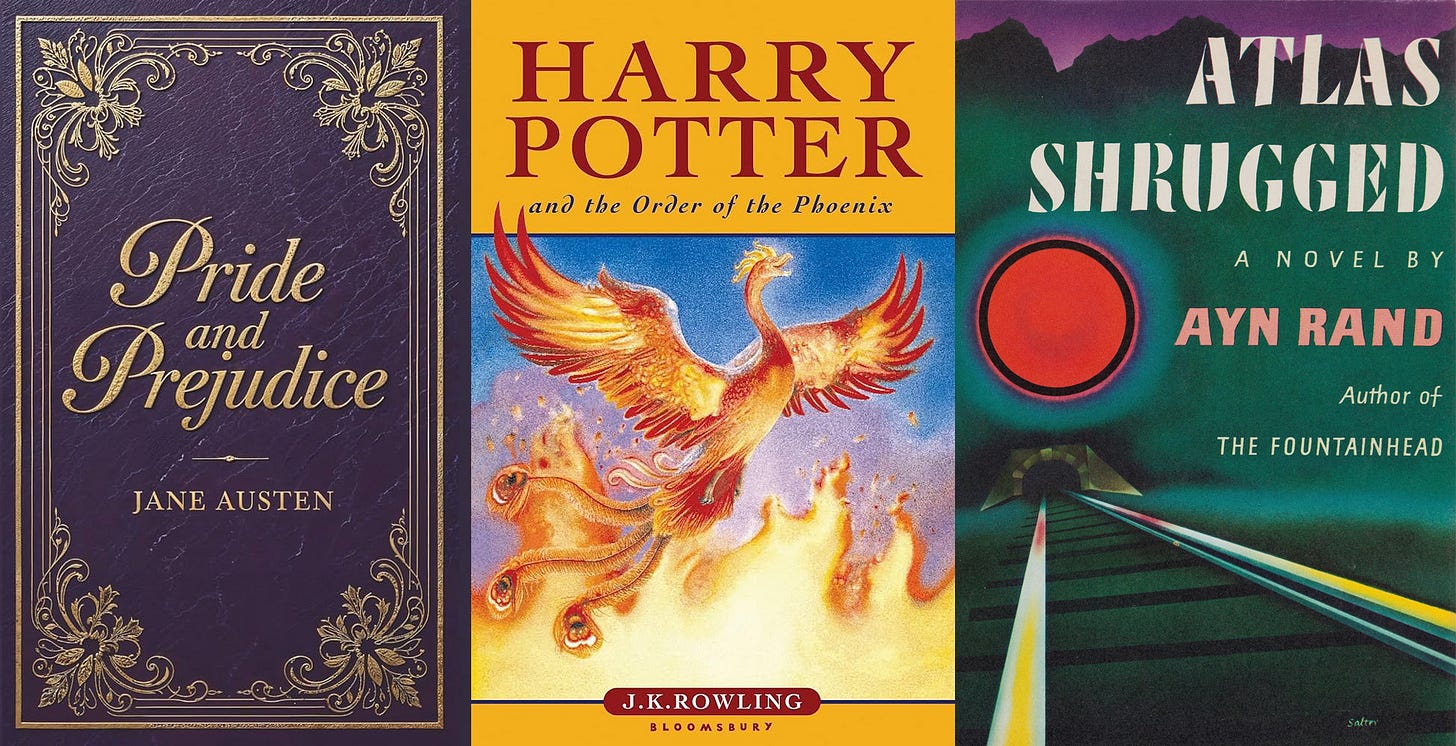

Next, we will look briefly at the stages of a growth arc. Then we will go through them in three examples. From each of those examples, I will pull out the lesson, unpack it within the context of the theme, and highlight a few points that may be useful. The examples will be Lizzy Bennet from Pride and Prejudice, Hank Rearden from Atlas Shrugged, and Neville Longbottom from Harry Potter. In the case of the first two, I will not spoil the endings. In the case of Harry Potter, I will spoil the end of Neville’s arc, but I will only rely on material in the movies, not what is exclusively in the books. I think these three are all phenomenal works of fiction with lots of great ideas and lots of value, but they’re from different eras, different genres, and different authors. You can find great arcs and great themes in the works of many authors, in any genre and any era. Finally, we’ll wrap up with a few takeaways to help you apply this to your life.

There are many different ways to break down character arcs, some with as few as three steps and some with as many as twelve. Here, I will use seven steps because most fleshed-out character arcs have at least these seven elements.[3]

These stages refer to events in both the characters’ external world and to some extent the characters’ internal worlds. What are they thinking? What are they feeling? What are they going through? This is important because we all live this way, too. We have people we talk to, things we doing, stuff that’s happening in the outside world around us. We also have our thoughts and our feelings. We experience life as both external events and actions and as internal ones—so it’s helpful to use a character arc structure in which we can see both of those.

The first step is the initial state. What’s happening with the character when we start the story? Internally, he has limited awareness. Whatever his or her core problem is, the character is either not at all aware of it or has only limited awareness.

Step two is the catalyst. Something happens that sets the main conflict in motion or draws the character into it. Perhaps he meets somebody, or something changes in his situation. This leads to increased awareness; he is now, to some extent, aware of the problem or aware of whatever the challenge will be.

But change is hard, so next comes step three: resistance and struggle. Depending on the nature of the challenge, there may be external problems or mostly internal struggles. In a really well-integrated work of fiction, you have some of both. Depending on the length and complexity of the work, the character will face one or more tests that he must work hard to get through. At some point in that process, he commits to change; at some point he says, “I need to do something differently.”

This is step four: transformation. To get there, the character must undergo some self-reflection and learning, which can be instructive for readers as well.

Then comes step five: trial by fire. In sci-fi or fantasy, this might be a big battle. In other genres, it might be more subtle. But there’s a big, high-stakes challenge through which we see that the character has changed or transformed. He’s putting his new character traits to work.

Then there’s the follow-up from that in step six. Because we’re talking about growth arcs, these will be mostly positive things; there may be external rewards and/or emotional rewards, such as pride.

In real life, even if we actively work on ourselves and we make a change, that’s not the end; it’s not like we reach virtue, and we’re done growing. We must keep doing it over and over. Over time, it becomes easier because it becomes part of us. But, often, there are still struggles wherein we will have to prove that the lesson truly stuck. This is the seventh step of a growth arc: a resurrection or a final attempt. The character must be tested one more time before the author concludes, “OK, now he has it.” At that point, he is finally and fully a new, better version of himself. In summary:

Initial state | limited awareness

Catalyst | increased awareness

Resistance | struggle

Test(s) and committing | self-reflection and learning

Action | transformation

Consequences/resurrection | reward/final attempt

New state | new state

Elizabeth Bennet: Reality Orientation

Lizzy Bennet from Pride and Prejudice is the second oldest of five daughters. Her father is a gentleman, so she and her sisters have a certain social status, but they’re not very wealthy. The daughters will not inherit the estate, which leaves them with a problem because this is early-19th-century England—it’s not socially acceptable for them to work, and they don’t have any skills that they could make money with anyway. Their only option to avoid poverty is to marry men who are at least moderately wealthy. Lizzy does not want to marry for money; she wants to marry for love and have a happy life. But she’s not in a rush, even though they live in a small town with few eligible bachelors. Her mom wants her daughters to have good, comfortable, stable lives, but she’s overbearing in how she tries to achieve that. Mrs. Bennet is very direct, over-the-top in her emotional reactions, and sometimes even rude in social contexts. Despite these pressures, Lizzy finds things to enjoy in her life. She’s close to her older sister, she likes to read, and she likes to go for walks. She’s generally pretty content at the beginning of the story.

Then the catalyst happens: Two eligible bachelors arrive in their small town. They’re both very wealthy and handsome, and they show up to a ball. One is friendly and starts to fall in love with Lizzy’s older sister, Jane, right away. The other one is Mr. Darcy, who is standoffish and kind of arrogant. His friend encourages him to dance with people and have a good time, but Mr. Darcy says he doesn’t want to dance and that it would be intolerable to dance with any of the ladies there. His friend replies that there are many pretty girls there, but Mr. Darcy disagrees. He looks at Lizzy and says, “She is tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me.”[4] Lizzy heard him. She is quite offended, though she laughs it off because that’s her character; she’s fun and playful and she likes to laugh at people being stupid or silly. Lizzy is not yet aware of the problem, but this is the incident through which she will become aware of it. She must meet Mr. Darcy to start her journey.

Throughout the next third or so of the book, Lizzy grows to dislike Mr. Darcy more and more. Different things happen, the most dramatic being that she hears a lie about Mr. Darcy. She believes it even though she doesn’t know the person telling it well. If it were true, it would mean he is an immoral person. The next time they’re at a dance together, Mr. Darcy asks Lizzy to dance, and she says no. She’s hesitant and doesn’t want to get involved with him. Later, he convinces the friend who is falling in love with Lizzy’s older sister to leave town because he doesn’t think that it would be a good match. This obviously leaves her sister heartbroken; and Lizzy, being close to her sister, is very upset about this. So, throughout the course of several chapters, Lizzy comes to dislike Mr. Darcy more and more. Mr. Darcy is trying to make amends for the initial offense in his own way, but Lizzy is completely oblivious to this. He corrects other people’s rudeness to her, asks her to dance, and so on. She wonders what this could possibly mean but makes no effort to find out; she goes right on with her life.

Then comes her big test after Mr. Darcy proposes to Lizzy, who has been completely unaware of the fact that Mr. Darcy is interested in her. He proposes in a rude way, saying, in effect, “Your family is way beneath me, but for whatever reason, I still love you. So, will you marry me?” Unsurprisingly, she refuses in no uncertain terms. When he asks why she doesn’t like him, she explains the things that she thought problematic about his behavior and reveals the lie that she had heard about him. Mr. Darcy leaves but then writes her a letter in which he tries to explain the two big problems: why he convinced his friend to leave town and the lie about his previous behavior.

This is Lizzy’s big test. She has the evidence on the table—what will she do with it? She thinks it over seriously. At first, she doesn’t want to believe it. Then, she realizes that it could be true; if she rethinks the behavior of the people involved, it’s possible. She realizes that she didn’t have enough evidence to evaluate the damning claim about Mr. Darcy. She was completely flattered by the liar and offended by Mr. Darcy, so she was inclined to believe the one who had flattered her even without evidence. She says, “Pleased with the preference of one, and offended by the neglect of the other, on the very beginning of our acquaintance, I have courted prepossession and ignorance, and driven reason away, where either were concerned.”[5] In this moment she commits to change. Jane Austen writes lovely scenes for several of her heroines wherein they realize they’ve erred and need to do better; the scenes include a thorough, thoughtful understanding of the heroine’s mistakes and what she needs to change. This is Lizzy’s moment of change.

She has the chance to put it into action when she meets Mr. Darcy again by accident after the failed proposal. Lizzy is determined to be nicer to him and to be more objective about his behavior. She takes seriously the fact that the people closest to him, such as his sister and the housekeeper who’s known him since he was four years old, have a very high regard for him that does not match what she had thought about him before. Mr. Darcy, too, goes through a bit of an arc and is behaving differently by this stage. I won’t spoil the ending, but the theme of the work is that you need to be focused on reality; you need to keep your mind connected to what is going on if you want to be happy, live a good life, find the right partner, and make the right decisions. Lizzy learns that if you want to be happy, you cannot let prejudice blind you to the facts.

These growth arcs often include push and pull factors—something that’s nudging the character gently (or not so gently) toward doing better and something else that’s enticing him or some kind of reward if he succeeds. In Lizzy’s case, the push is the evidence of Mr. Darcy and the pull is the romance—the facts that a potential relationship is there as well as something about Mr. Darcy that appeals to her despite her initial dislike of him. Her key opportunity for change is Mr. Darcy’s letter; if she had disregarded that, she would never have gone through the change that she did.

Hank Rearden: Integrity

Next, we have Hank Rearden from Atlas Shrugged. Hank is not the main character, but he’s an important character. He is a successful businessman who owns many steel-related businesses. When we first meet him, he has just invented a new alloy: Rearden Metal. It’s cheaper, lighter, and stronger than steel; and it’s now real rather than theoretical, so he should be ecstatic. And he is—at first, when he’s at work seeing this metal being poured—but then he goes home. Then we realize that he is, in fact, very lonely. He reflects on the fact that he feels loneliest when he’s happy or has achieved something. This is because of his family (but he doesn’t know that yet). He lives with his wife, mother, and brother, all of whom expect him to sacrifice for them because they are his family—even though they don’t care about him. They don’t care about the things that he cares about. In fact, they tell him sometimes that he is a terrible person, a terrible brother, a terrible husband. He thinks that they must be right. He knows what he’s doing at work, but when it comes to his emotions and his people skills, he doesn’t feel confident.

His arc has a double catalyst. The first is meeting Francisco d’Anconia at a party. Francisco is a wealthy businessman from an aristocratic family. Early in life, he was very productive, but then he turned into a playboy who doesn’t work, wastes his money, and is promiscuous. Hank has a pretty low opinion of him, but when they meet, Francisco thanks Hank for his achievements. He offers Hank gratitude and encourages him to think about who is benefiting from his work. At first, the honesty and the gratitude completely shock Hank, and he’s startled into a vulnerable position. Then, he remembers what he thinks he knows about Francisco and rejects the aristocrat’s friendship.

Next comes Hank’s relationship with Dagny Taggart, the heroine of the story and herself a capable businesswoman. They work together on a joint project after knowing each other professionally for some time. Then, after a massively successful first test, they begin an affair. It’s a celebration of their victory, but at the same time, Hank feels that it’s wrong. He’s cheating on his wife, so in a sense it is wrong, and he condemns both himself and Dagny for it. He has an intense emotional struggle because, on one hand, he knows that she is the kind of person he wants in his life. On the other hand, he feels a sense of duty to his wife despite her almost total lack of positive qualities.

Then comes a series of tests for Hank, a number of things in his personal and professional life that directly threaten or undermine what he cares about most. For instance, the government tries to stop him from selling Rearden Metal to the people he wants to sell it to. They blackmail him a few times. Also, his wife learns about his affair and demands that he stop it. When she learns with whom Hank is sleeping, she demands even more insistently—and he refuses.

Later, Dagny goes missing. This really distresses Hank because it disrupts what is, at this point, a strong bond between the two of them. He had been seeing how she loves her life fully and without guilt. She’s an integrated person who has inner peace no matter what’s happening around her because she knows what she stands for—and why. She knows what she wants and what she will do about it. Being able to absorb those lessons from Dagny—especially about having the same standards and fundamental approach to her personal life and her work—leads Hank to realize that he deserves better and that he can, if he behaves in a more integrated and principled way throughout his life, be happier, though it will take a lot of effort. He also realizes that he had been thinking about love and sex in the wrong way—as though they were separate things. He starts to realize that that’s not true at all—his attraction to Dagny is rooted not primarily in her beauty but in her character.

The climax of their relationship comes when, as a result of government blackmail, Hank is about to give up the rights to Rearden Metal. If he refuses, the government will make the affair public. The story takes place in the 1950s, so Dagny’s reputation would be completely destroyed. Dagny says that she doesn’t care, and she makes it public without Hank’s knowledge. Afterward, he realizes that Dagny has met someone else, so he has a conversation with her in which he lets her go and integrates all the lessons he’s been learning from her, from Francisco, from his battles with the government, and from thinking through his values. Around the same time, he also cuts off his family, realizing that they are completely in the wrong for hating him and for abusing him—while also depending on him, no less. After integrating these lessons about love and justice, he is content and proud. He has a long conversation with Dagny about it, of which this is a representative sample:I love you. As the same value, as the same expression, with the same pride and the same meaning as I love my work. . . as a shape of my world, as my best mirror. . . . I, who took pride in my ability to achieve the satisfaction of my desires, let them prescribe the code of values by which I judged my desires.[6]

He’s applying what he’d been applying in one field (work) where he hadn’t been applying it before (his personal life), and by integrating those he becomes one full person who consistently acts on his values. Hank starts appreciating that you can cherish the same fundamental, core values in a situation at work, in a challenge, in an opportunity, and in a person. He also realizes that he shouldn’t be letting other people prescribe his values—he must think for himself in ethics just as he does in steelmaking.

Hank’s resurrection comes when armed government agents attack his most important steel mill. He’s oddly calm during this attack because he realizes that although the government can take specific things from him—a mill or a particular person—they can’t take the values that those things and those people embody. They can’t take his mind or his values—the most important elements of his self.

As I mentioned before, the theme of Atlas Shrugged is the crucial value of the human mind; Hank learns to apply his mind fully and in all areas of his life. He’d been applying it at work, and that’s why he’d been so successful. He hadn’t been applying it with his family or romantic relationships. He finally learns that he is capable of doing so and that he must do so if he wants to be an integrated person. He learns that morality is not a duty forced upon him but the means by which he can live and thrive.

The “pushing” forces in Hank’s story are the politicians and the people who are morally aligned with them, including his wife and his brother. The “pulling” forces are his mentors, Francisco and Dagny, who were showing him another way. They weren’t preaching at him—they were appreciating him, connecting with him, and being role models. His main opportunities were meeting Francisco and having the relationship with Dagny—in short, getting to observe and interact with these people and connect with them in a way he had never really connected with people before.

Neville Longbottom: Courage

When we meet Neville, he’s a shy, pitiable, clumsy little boy. He has been raised by a strict grandmother who has high expectations of him and who scares him a little bit. His family members worry that he is not magical, which would carry a major stigma in the story’s world. He comes to Hogwarts (the school for wizards) nervous, unconfident, and afraid that he doesn’t belong there—but he tries anyway. For the first few years, we see him trying: standing up for himself; sticking to his values in small, quiet ways; and doing OK despite having many problems.

The core of his growth arc kicks off in the fourth book and movie. In this story, a new, intense, and suspicious teacher arrives to teach defense against the dark arts. This teacher, Professor Moody, shows them the torture curse. This is significant because Neville’s parents were tortured to insanity by that very curse, which is why he lives with his grandparents. Seeing what happened to his parents in the form of a classroom demonstration absolutely terrifies Neville, but it also makes him realize that he currently has no way to stop the people who inflict such pain on others. This is the catalyst that sets him on the path to realizing that being good at magic isn’t just about being accepted or having friends—it’s a way to defend the things and people he cares about.

Neville really puts that into action in the next movie when Bellatrix Lestrange, the lead torturer of his parents and a follower of the Dark Lord, escapes from prison. Now he is really focused, really determined, and a little bit angry. Her escape gives him a sense of purpose. He’d already joined a group that was studying defense against the dark arts to prepare to defend themselves against the Dark Lord (Voldemort) and his followers, but now Neville really commits to the cause. He works harder than anyone has ever seen him work. Before, he had been driven by fear; he’d been afraid of making mistakes. Now, he’s driven by purpose. He has something he cares about that he’s working toward, and he starts to succeed. As he does, Harry and his other allies cheer him on and give him advice.

Neville finally has an opportunity to use his training at the end of the fifth movie. Initially, Harry doesn’t want to bring him along because he still thinks of Neville as a clumsy, forgetful boy who’s not that good at magic and lacks courage. But Neville points out that all their training was supposed to be about fighting the Dark Lord, and this is the first chance he’ll have to do something real. He doesn’t want to just have the skills—he wants to use them. So, he goes, he fights the followers of the Dark Lord, and defends his friends. He’s scared; he’s never faced these kinds of people—brutal torturers and murderers. But he does what he has to do to keep his friends safe.

Neville becomes a hero. He knows that he has the right to be in the wizarding world and that he belongs at Hogwarts. Later in the series, when the Dark Lord has taken over Hogwarts, Neville leads the student rebellion. He’s now putting his courage and skills to work against the people who are torturing and hurting him and his fellow students. He stands up for those who cannot stand up for themselves, as well as mentoring them and teaching them some of what he’s learned. Finally, Neville has the chance to kill Voldemort’s snake, which is essential to the villain’s defeat. He stands up to Voldemort in front of everyone. This is his transformed state; he is now brave, courageous, and standing up for what he loves. He is no longer just a citizen of the wizarding world but a hero of it.

Overall, the theme of Harry Potter is the power of love. We see different kinds of love throughout the series, including familial love, romantic love, and love between friends. Neville learns to defend what he loves. It’s not enough to feel that you love things or people—loving them means standing up for them. His “push” is wanting to be prepared to defend himself and his friends against Voldemort’s followers and perhaps wanting to avenge his parents. His “pull” is the support of his friends. His opportunities for becoming the kind of person he wanted to be and the kind of wizard he wanted to be were the study group in the first case and the student rebellion in the second case, and he seized those opportunities with both hands.

***

Now that we understand what a growth arc looks like, how can we apply this to our own lives? Most obviously: The specific lessons the characters learn could be things that would help you in your own life, whether they’re areas you need to work on or simply principles worth remembering or thinking about. We can train ourselves to view challenges not only as obstacles but as opportunities to develop new skills or to change a mindset that might be holding us back.

We can build our own growth arcs by setting a standing order always to be on the lookout for allies and mentors who share our deepest values. Notice how much of a role other people played in Lizzy’s, Hank’s, and Neville’s journeys. It wasn’t the teachers, parents, or authority figures who had the biggest impact (although such people certainly can be role models and allies)—it was the friends who were supporting them or the romantic partner who inspired them. We can try looking for “push” and “pull” factors in our own lives—forces that nudge us away from behaviors that may not be good for us and toward better alternatives. Applying this reframes challenges and lets you see struggles not as just something inevitably there that you get through as best you can but as opportunities for you to decide that you will become the kind of person who can deal with it.

If we recognize the power of real-life growth arcs and consistently pursue them in our own lives, we find that we really can become the heroes of our own lives.

This article appears in the Spring 2026 issue of The Objective Standard.

[1] Yen Cabag, “How to Write Character Arcs: Adding Depth to Your Story’s Players,” TCK Publishing, accessed January 15, 2026, https://www.tckpublishing.com/how-to-write-character-arcs/.

[2] The term “hero’s journey” originated with Joseph Campbell, who wrote a book called The Hero with a Thousand Faces, in which he looked back at mythology and old stories and asked “What do these heroes have in common? What is the structure that all of these stories share?” What he articulated has since served as a blueprint for many fiction writers.

[3] Amy Jones, Character Arcs & Archetypes, (Glastonbury, England: Wooden Books Ltd., 2023), 33.

[4] Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (Ware, England: Wordsworth Classics, 2007), 13.

[5] Austen, Pride and Prejudice, 177.

[6] Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged, (New York: Signet, Kindle edition), 804-05.

Thank you for the article. I think that as they grow up, most people, almost regardless of their core values, have a sense that they get one life (of this kind if they believe in an after life. Who knows what goes on in the thoughts of those who believe in reincarnation.) and when the big decisions and challenges come up, they want to get them right/meet them well. So in a sense, well written stories are manuals for a good life and we all want as much of that as we can get.

RAND’S ACADEMY

I first read Atlas Shrugged in 1965. As I have argued in previous articles, the scene near its conclusion in which Ayn Rand creates the greatest integration of subject, plot, theme, and characterizations I have ever read, leads to the satisfying culmination of the story. A story that continually displays examples of both Rand's philosophical genius and literary skill.

There are many examples in Atlas Shrugged that illustrate Rand's educational "academy" -i.e., the profound philosophical education that IS Atlas Shrugged. In the context of this article, her philosophical moral academy.

The more-obvious one, such as the incredible artistic integration I reference above, wherein Taggart actually loses "touch" with his mind, imposes itself on the reader much as does uncomfortable heat from being too close to fire, or the comforting warmth of sunlight on the skin. Dramatically alarming, stimulating, rationally satisfying.

Another example, though perhaps more subtle - yet shocking, occurs just prior to Taggart's forced "escape" from reality. It is when Dagny confronts the guard preventing her access to where Galt is being tortured. She asks this image of a human being to make a decision? I chose the word "image" because this creature was absent the "political" authority to do so. No one had "authorized" him to act as Dagney had requested, a request in conflict with his existing "authorizations." Dagney was, therefore, only calling on what might remain of his inherent moral authority. An authority "normally" present in each of us, an aspect of our nature that contributes to our natural "humanity!"

He remains fearfully-unable - even in the face of the threat of imminent death, to regain this distinctly human moral authority. A long-since suppressed capacity, surrendered to who knows what for what knows why..........

When, in this state of now-inescapable fear, confusion, and bewilderment, he cannot make the decision that will save his life, Dagny, without a second thought, kills him and relieves him of his terror at being held "responsible!"

Rand demonstrates that her heroine had become keenly aware of that which she was confronting and had little qualms in dealing with it!

Here, in addition to literary skill, Rand dramatically illustrates profoundly-abstract moral and psychological principles - principles woven throughout the entire novel. Principles using simple concrete illustrations! In this case, the illustration of the potential consequences to a human being from surrendering their inherent moral authority. Made to contrast with Dagney's demonstration of moral authority which is rationally understood and accepted. Subsequently, leading to it being confidently acted upon!

Rand's genius continually amazes me! Continues through this moment in my 81st year. Continues, after subsequently reading Atlas Shrugged four additional times since 1965!

Dave