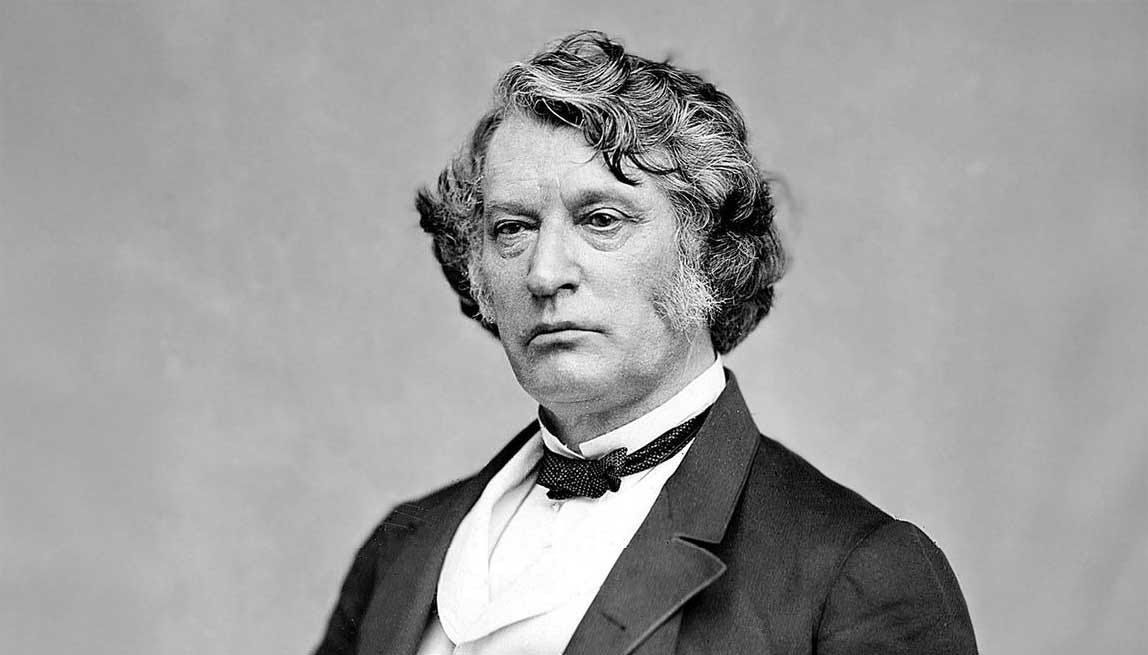

Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner was that rarest of political creatures: a deeply principled man who nevertheless rose to the highest levels of government power. Best remembered today as one of slavery’s most vocal enemies, he was also a leading scholar of international law whose achievements included overseeing the annexation of Alaska.

Despite his heroic status, however, his story has been strangely neglected. David Herbert Donald’s two-volume biography (consisting of Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War [1960] and Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man [1970]), appeared a half century ago and remains the most thorough examination of Sumner’s extraordinary career. Between then and now, only two books about him have been published: an obscure biography by history professor Frederick Blue and the superb Young Charles Sumner by Anne-Marie Taylor, which, however, only covered his pre-Senate life.

Even more regrettably, Donald’s books were tainted by an undercurrent of disapproval. Viewing politics as an art of negotiation and compromise, not rigid adherence to principle, Donald considered his subject insufferably dogmatic and pompous—and consequently a failure as a legislator; “hardly,” Donald concluded, “among the greatest of statesmen.”[1] Yet Sumner’s attitude toward politics was almost exactly the reverse. He thought it his job to speak the voice of conscience—to attack the evil and promote the good while leaving the technical details of legislation to others.

Now, at last, Stephen Puleo and Zaakir Tameez have set out to make up the historians’ shortfall. That’s certainly welcome at a time when many Americans are hungry for stories about the nation’s heroic champions of equal rights. Unfortunately, however, their books—while making important progress toward presenting Sumner to a new generation—suffer from significant flaws of their own. The definitive life story of this nemesis of slavery remains to be written.

Sumner was born in 1811 into an emotionally cold family. His relationship with his father was especially loveless, which may have inflicted lasting consequences on the son, whose life was haunted by solitude. Although he developed some passionate friendships with men, notably including poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and abolitionist Samuel Gridley Howe (whose wife, Julia, wrote “America the Beautiful”), he never felt comfortable around women. His brief attempt at marriage—in 1866 to an ill-tempered woman nearly half his age—ended within months in a scandalous divorce, the highlights of which included his ex-wife publicly accusing him of impotence. (Some biographers, including Tameez, have speculated that Sumner was gay, but there’s no evidence of this, either.) In his later life, Sumner often openly wept over his bitter sense of personal loneliness.

Sumner’s father was the sheriff of Suffolk County, Massachusetts, and, as Tameez notes, situated his household in one of Boston’s black neighborhoods. He appears to have been remarkably advanced in his views about race and passed those views to his son, along with a rare educational opportunity: The elder Sumner persuaded U.S. Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, a friend of his, to take the boy under his wing. Thus began a legal education that fashioned Charles Sumner into one of the most important scholars of American constitutional law. Along with former president John Quincy Adams, Story taught him that the Constitution should be interpreted in light of the Declaration of Independence, meaning that whenever possible it should be construed as affirming the classical liberal principles of equality and individual liberty.

Armed with these ideas, Sumner would spend his career working with other abolitionists, such as future Chief Justice Salmon Chase and former slave Frederick Douglass, to fashion an antislavery constitutional theory that, after the catastrophe of the Civil War, was vindicated in part by the ratification of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments.

Sumner’s legal career never flourished because matters of principle interested him far more than the mundane practice of law. But he did make history in 1850 when, joining forces with a black attorney named Robert Morris, he sued the city of Boston for maintaining segregated schools. Anticipating the arguments that would prevail in Brown v. Board of Education almost exactly a century later, the pair charged that segregation violated the state constitution’s acknowledgment of the fact that “all men are born free and equal.” The Massachusetts Supreme Court rejected their argument, but the publicity helped gain Sumner a seat in the U.S. Senate a year later.

Once there, he unleashed a torrent of elaborately constructed antislavery speeches, some lasting five or six hours and—amazingly—delivered from memory. The most famous came in May 1856, when he excoriated slavery’s defenders for their violent efforts to expand that practice into the territory destined to become Kansas. He employed the whole range of classical oratory, including, in one remarkable metaphor, likening slavery to the prostitute Dulcinea from Don Quixote and its defenders to the delusional main character of that novel. Speaking specifically of pro-slavery Senator Pierce Butler, Sumner said:

The Senator from South Carolina has read many books of chivalry, and believes himself a chivalrous knight, with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean the harlot, Slavery. . . . The frenzy of Don Quixote, in behalf of his wench Dulcinea del Toboso, is all surpassed. . . . Heroic knight! Exalted Senator![2]

These were fighting words at a time when dueling was common, and Southerners were increasingly insisting that slavery was not just a legal or economic institution but part of their cultural identity; criticizing it meant attacking their honor. Two days after the speech, Butler’s cousin, Congressman Preston Brooks, approached Sumner in the Senate chamber and clubbed him on the head repeatedly with a cane made of gutta-percha, a kind of wood that has the same density as lead. Sumner barely escaped with his life. He spent two years absent from the Senate, recuperating in European hospitals.

Butler was cheered as a hero in the South, but the grotesque incident also helped rally antislavery forces. As Puleo notes, “His vacant chair [in the Senate] spoke volumes about the evils of slavery and the Southern Democrats who supported it. . . . If the caning had unified the South, must not the North also unify to protect its interests and its constitutional rights?” (172–73).

When Sumner returned at last, his colleagues found him only more impassioned. In another hours-long speech titled “The Barbarism of Slavery,” he covered the entire history of human bondage, describing it as the enemy of civilization and Christianity. “Slavery must be resisted not only on political grounds, but on all other grounds,” he exclaimed. “Ours is no holiday contest . . . but it is a solemn battle between Right and Wrong; between Good and Evil.”[3]

Union victory in the Civil War five years later gave antislavery leaders the chance to rescue the Constitution from misinterpretations foisted upon it by pro-slavery lawyers and judges. Sumner was among those most eager to seize that opportunity. Not only did he back the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended the practice, but he also argued that the amendment gave Congress power to outlaw even private discrimination in theaters, restaurants, and streetcars. In his view, the amendment forbade not only compelled labor but all “badges and incidents” of slavery, too, including racial discrimination—a view the U.S. Supreme Court endorsed in 1976.[4] Sumner went even further than that. Citing a clause of the Constitution that guarantees a “republican form of government” in each state, he proposed seizing former slave plantations and redistributing the land to the freedmen on the theory that this would better secure “republicanism.”

Even Sumner’s allies thought that was going too far; republicanism, argued Frederick Douglass, depends more firmly on guaranteeing private property rights. The proposal never came to pass. In fact, most of Sumner’s ideas never became law. His greatest legislative achievement, the 1875 Civil Rights Act, was heavily watered down before Congress adopted it—and it only did that after his death. Still, he did prove an effective leader as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He spearheaded the effort to acquire Alaska from Russia, for example—an idea many considered folly at the time. As Tameez notes, he even appears to have given it the name “Alaska.” Before that, it was largely known as “Russian America.”

This list of accomplishments richly deserves the attention of historians, and Tameez and Puleo do a fine job of mustering the details to portray a man who, despite the significant failures of his personal life, was a noble voice of principle in an era when the nation’s values were tested in unprecedented ways.

Yet both books are hindered by stylistic and substantive faults that undermine their efforts to celebrate the great senator. Tameez’s Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation in particular is incompetently edited; riddled with misspellings, grammar errors, and even mistakes of fact, such as when he repeatedly gets General William Sherman’s name wrong (calling him Tecumseh, which was his middle name [398, 426, 519]) and claims that the 2011 earthquake in Virginia “nearly caused [the Washington Monument] to collapse,” which it did not (533). He employs jarringly modern turns of phrase such as “top of mind” (345, 443) and “the N-word” (535), and many of his word choices are bizarre or inappropriately colloquial—for example, referring to two Confederate agents who were captured as having been “abducted” (262), calling the Battle of Gettysburg a “morbid calamity” (298), claiming the Union naval blockade was intended “to squeeze the Confederate economy by crushing any commercial southern vessels” (293), describing the “republican form of government” clause as a “wiggly phrase” (300), referring to a person’s “notorious reputation” (294) (all notoriety is a form of “reputation”?), and saying someone sought to “avoid paparazzi” (a strange term for an age before portable cameras). Tameez often simply uses the wrong word, such as when he describes a consolation prize as a “conciliation prize” (457), refers to a person’s “falling health” (failing?) (454), says Sumner wore a “nightgown” to bed (434) (presumably, he wore a nightshirt), and remarks that he indicated “his vicious opposition” to the arrest of fugitive slaves—when surely it was virtuous (249). Other times, Tameez commits accidental puns, as when he says Sumner was “heartened” to receive a visit when ill with a cardiac condition (512).

In one especially disconcerting moment, Tameez feels it necessary to explain in detail that Don Quixote is “a famous Spanish novel [about a man] who deluded himself into thinking he was a chivalrous knight . . . [and who] picked out a prostitute as his maiden and recruited his neighbor as his squire” (191). One would hope readers willing to conquer a 629-page book about a Civil War senator have heard of Don Quixote. Worse still, he employs distracting “woke” concepts: capitalizing “Black” but not “white,” condemning as “specious” the idea that the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections for “persons” extends to corporations—when this is not specious and was not controversial in Sumner’s day (531)—and baselessly asserting that Sumner’s coining of the name Alaska was “a land acknowledgment” intended to “atone” for the “legacy of enslavement, slaughter, and exploitation that Native people had endured” (379). He absurdly claims that Sumner’s support for the post–Civil War Freedmen’s Bureau was based on “a logic similar to that for many modern arguments for reparations” (325), and most astoundingly, even accuses Sumner of “racism and Western supremacism” for saying slavery was barbaric (235).

Puleo’s The Great Abolitionist: Charles Sumner and the Fight for a More Perfect Union suffers from none of these flaws, but it’s not written in chronological order, and each chapter is made up of small subsections, most less than a page long, separated from one another by asterisks—a technique typically only used in fiction. That, combined with frequent single-sentence paragraphs, gives the book an uncomfortably histrionic quality. Worse is his choice to relegate the entire post–Civil War decade to a mere sixty-four pages. He never mentions Alaska.

This is unfortunate to say the least. At a time when incidents such as the “1619 Project” have attempted to rewrite history with stunning audacity, Sumner and other American heroes deserve first-rate biographies. He was an eloquent, unbending man of integrity—the opposite of what is generally considered a “practical politician,” willing to sacrifice principle for temporary advantages. Yet today we can see that what he demanded—a nation true to its founding principle of equal liberty—was more practical than the temporizing, compromising, and rationalizing that so long delayed the death of slavery and segregation, and increased the cost—in blood and money—of the eventual triumph.

“Men ordinarily find in the Constitution what is in themselves,” Sumner once said, meaning that people often read their own pet notions into the nation’s fundamental law (Tameez, 411). If that was true of Sumner himself, then it was for the better—because what he found in his own soul was a commitment to freedom for all.

This article appears in the Winter 2025 issue of The Objective Standard.

[1] David Herbert Donald, Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man (New York: Knopf, 1970), 8.

[2] Charles Sumner, The Crime against Kansas (Washington, DC: Duell & Blanchard, 1856), 5.

[3] Charles Sumner: His Complete Works, vol. 5 (Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1873), 10.

[4] Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976).

You have an interesting take. The source of the problem is many writers try claiming slavery as the cause of the Civil War (protective tariffs were the cause as they were in the Republican platform in 1860). President Lincoln actively worked against abolitionists again, and again. He invaded the South and nearly lost the war. His Emancipation Declaration was supposed to cause an insurrection among the slaves and it did not happen, but it did change how the rest of the world viewed the conflict.

No one ever bothers to cover the conflict between Lincoln and the Abolitionists. What was accomplished with the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendment is the result of the persistence of Abolitionists to confront adversary after adversary to obtain results for freedom which last to this very day.