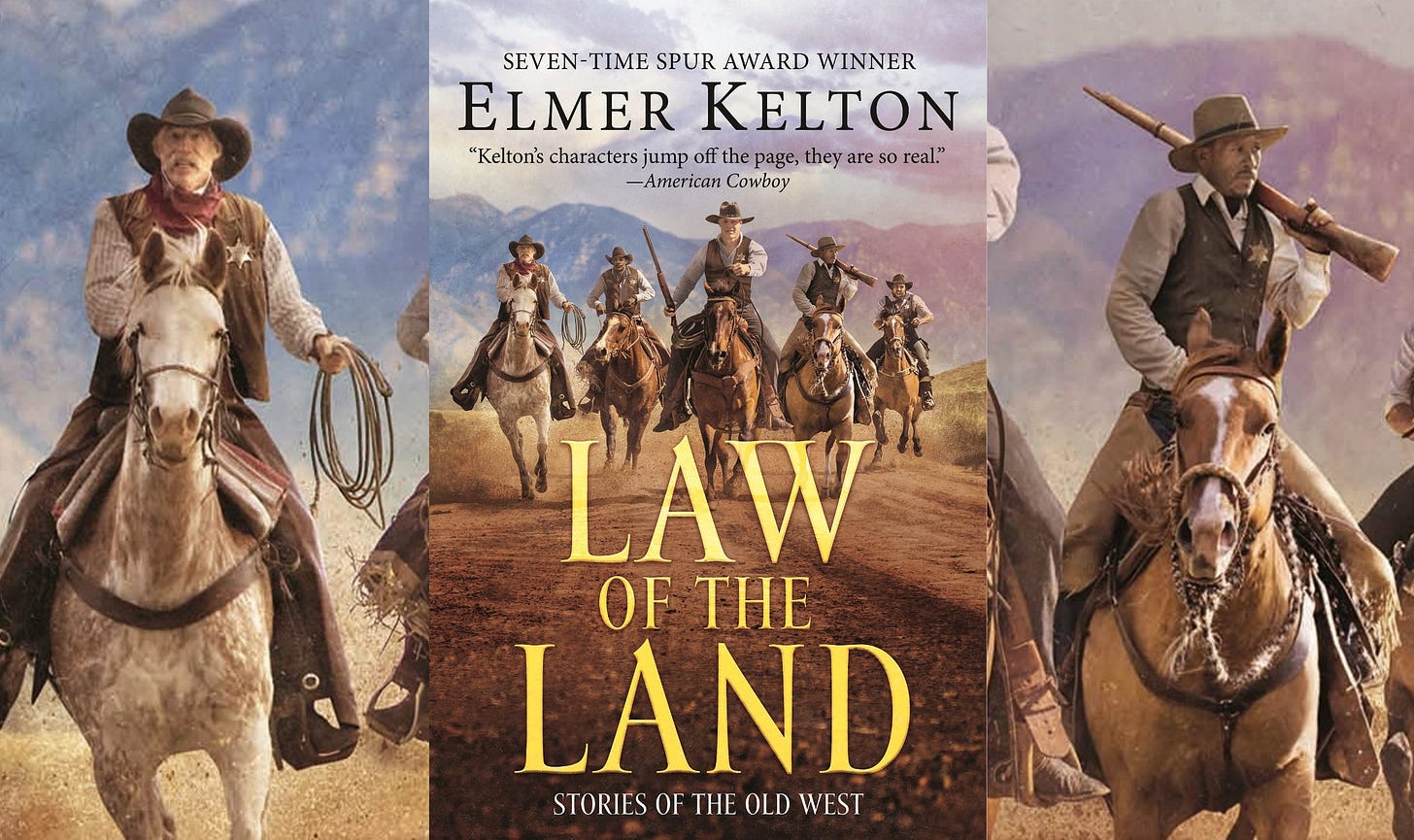

New York: Forge Books, 2021

320 pp. $27.99 (hardcover)

The late Texas writer Elmer Kelton is well known to fans of Westerns. He was even named the “greatest Western writer of all time” by the Western Writers of America. Yet few among the broader reading public have ever heard his name. Whereas the nation’s leading literary critics gave renown to such auth…