Author’s Note: This interview is an excerpt from an episode of the Reason for Living podcast.

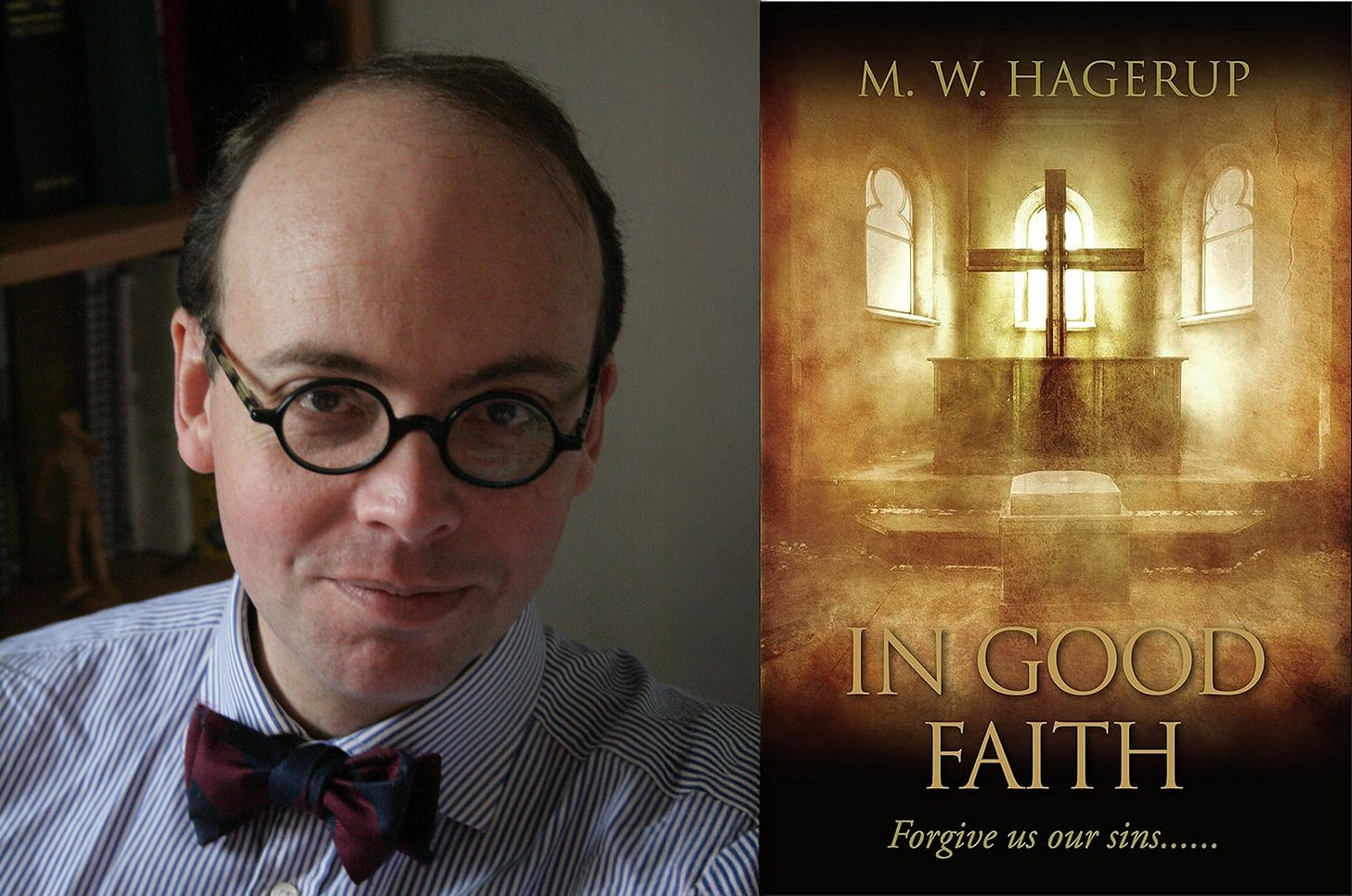

Thomas Walker-Werth: I’m joined today by William Hagerup. He’s the cofounder of Agora Debates, a London-based debating society, and the author of In Good Faith, a novel memoir highlighting many of the dangers of organized religion. William, hi.

William Hagerup: Hello; it’s an honor to be here.

Walker-Werth: You were very religious in the early part of your life, but you later moved away from religion. What led you to that decision?

Hagerup: Well, it was quite a long process, really. But I should perhaps start by saying how I got into religion in the first place, because I grew up in quite a normal middle-class secular Norwegian family. We only went to church if there was a wedding or funeral or christening or that sort of thing. My parents wouldn’t even go at Christmas and Easter. They were just ordinary people, not really particularly religious at all.

But I always had an interest in the mystical and the occult as I was growing up. And when I became a young teen, I was listening to a lot of the sort of music where they use imagery of Satan and all that sort of nonsense—that fascinated me. I think it was a reaction against the sort of Christian morality that still dominates in our secular society. The morality of our society, albeit no longer explicitly Christian, is still based on Christianity, still based on a religious idea that you need to sacrifice your own self-interest for the good of others or for “the good of society.” I think something deep within me rebelled against that. With some of that quasi-Satanism, the notion was that you should just live according to your whims and follow your feelings, and that’s all good and fantastic. And part of me thought, Yeah, actually that’s great because if I follow that, I can’t be held for ransom by that Christian morality of self-sacrifice. But I didn’t have the knowledge to understand why that was the wrong solution to the problem.

But then, because I had such a deep interest in occultism, my sister, who was religious, invited me to a service at an evangelical Pentecostal church. And I got talking to a minister there who was from England, and he said, “If you don’t really believe that God is powerful, why don’t you let me pray for you?” And I thought, Yeah, that shouldn’t hurt. I can prove that he can’t change anything by prayer.

But of course, the real power of prayer is the power of suggestion. And a little while afterwards, I did have a very powerful experience that I guess some people would call a “spiritual experience” or revelation. I had what I thought was a very strong “vision” of God on the one hand, the devil on the other hand, and that the devil was bad and wanted to destroy me and put me through hell ever after. God was the good force in the universe who wanted the best for me. So that was such a powerful experience that I then chose to embrace Christ. And that was really what led me into religion. Then, of course, once that is firmly established in your mind, everything follows from that; if there is a God, and he has revealed himself in the Bible, and the Bible is true and is the word of God, then everything has to be seen through that light. That’s then how I spent the next ten years of my life trying to live according to that. I came to London to study at the Bible Institute of Kensington Temple.

What then led me away was many things but fundamentally two main elements. One was that I could not find honesty with myself in terms of the fact that I’m gay. It’s not something that’s overly important to me as a personal identity, but if you have to constantly deny the reality of yourself because that’s not how you’re “supposed to be,” then that becomes very corrosive—you feel like you have to deny yourself for the sake of the ideology you believe in.

But second, and perhaps more important, was the fact that wherever I looked around me within the church, I could not see the results that God and the power of the Holy Spirit were supposed to produce in people. I saw people who were miserable. I saw people who were not succeeding in life, who were actually worse people than many of the secular people I met outside the church. I did not see the results that we, as a charismatic, Pentecostalist, and eschatologist church preached and believed were supposed to be producing to engender the great revival of the end times, such as healing of sickness and the raising of the dead and all the miraculous things that were promised if you just believe in the power of the Holy Spirit. And at some point, you have to ask yourself, “If we’re not producing the outcome, then there are two possible explanations. One: the God and the Holy Spirit that are supposed to produce this have no power to produce it, which is a contradiction. If they exist, then they must have that power. Or the second explanation is: they just don’t exist. They’re just not there; they’re not producing the outcomes.” And so that was the notion that then eventually led me to think through my fundamental premises and come to embrace that there is no such thing as God and that I have to base my life on the powerful fundamental of reason rather than the shifty ground of faith.

Walker-Werth: You brought up something really interesting there, which is that a lot of people accept this false dichotomy between altruism and hedonism. On the one hand, there’s this Christian idea that you need to serve God, serve others—or a secularized version of that, that you need to serve the nation, serve society, serve the proletariat, whatever that external beneficiary is. Or the alternative supposedly is that you just follow your whims, that hedonistic approach, the distorted version of Nietzscheanism that we see kicking around in society today. And supposedly, there’s no third alternative. I think reason does bring you to a third alternative, and it sounds like you arrived there, too. So, what was that rational philosophy that you ended up adopting, and how did it affect your life?

Hagerup: Well, I got into politics at the age of sixteen, and I started reading Ayn Rand’s political essays and philosophic essays. Most people read her novels first, and then they get interested. Rand’s ideas cohabited in my mind with my religious faith for many years still because you’re able to compartmentalize very well when you’re a strongly believing person. Even the apostle Paul talks about this in one of the letters, where he says, “We see as through a glass darkly”; we don’t see everything clearly. God will make it clear to us at some point, but our reason is so limited. It’s basically the point that other philosophers throughout the ages have echoed that our reason is supposedly limited. So, I thought, Well, Ayn Rand obviously didn’t believe in God because she never had that revelation that I had. I could understand that’s rational if you haven’t had that, but I have had it.

So, I had to hold on to that while at the same time finding her thoughts really interesting. But I think once I started to come to the realization that something is wrong in the ideas of the church because we’re not producing the outcomes, then I came back to Rand’s thought. I think what really led me to understand, like you say, that there is this third way was the fact that she has a really well thought-through ethical philosophy. I think that’s one of the most interesting aspects of Rand’s thinking, her ethical philosophy—that there is a kind of self-interest that’s rational, based on values, and that those values have to be identified, and then you take the logical consequences of that one after the other. And I think that that really helped me on my way to thinking through my values definitely and to rebuild my worldview from the wreckage of my religious faith.

Walker-Werth: Yes, I found that grounding your values in the rational requirements of your life and using evidence to form your values and the principles you live by is really beneficial for your self-esteem as well. It gives you the knowledge that the values you’re upholding and living by in your life are actually correct and based on fact. Do you find that moving to a rational worldview has increased your well-being?

Hagerup: Possibly. I was never a morose, miserable person generally, even in my religious years, because even during my religious time I still identified certain things that gave me meaning and fulfillment in life. For example, I was very into music and singing. So, I made the musical part of my religious ministry a big part of how I expressed my faith. I tried to integrate my personal interests into my religious service. But I remember very clearly that when I finally came to that point when I could step away from religion, it was as if I stepped from the darkness into the light, and this burden just fell off. I’m almost using religious language here to describe my unconversion. Because it really was that. It was like I don’t have to now take all those precepts, those teachings, all those prefabricated conclusions—which is what religion is a lot of the time, a whole host of prefabricated conclusions, which you have to carry with you at all times. And it limits how you can think about anything. So, to be able to just get rid of those and to say, “Right, I can now start with a clean slate,” but the slate of reason and the discipline of logic.

It meant that I also didn’t have to accept the notion that my reason somehow is not good enough—that I have to humble myself before God and just do away with what I think is obviously true because some higher power tells me that that’s what I must think. So, that gives you a sense of self-esteem and self-worth. Not one that’s just based on “believe in yourself, and everything will be fine”—that sort of quasi-self-help notion that you find a lot out there. No, you need a reason to hold yourself in high regard. You need to base that on something. And that is what I was able to then identify—that I had a reason to believe in myself because I do have a rational mind and I am able to think through things logically based on fact, but also based on values, which I think are so important. If you don’t identify those things, then what happens to some people who lose their religious faith is that they fall into that hedonistic lifestyle. Because, like you said, in our society you have this false alternative between either you fulfill religious duties or you live like an Emperor Nero, just following your whims in every crazy way. No, there is certainly another way, and that’s the way of reason and values, which of course includes enjoying yourself but within a framework that enhances your long-term happiness.

Walker-Werth: When people leave religion, some, as you say, fall into that hedonistic lifestyle. But a lot just retain their Christian ethics and treat it like a floating system without any integration with the rational part of their worldview. I see that in a lot of the “new atheists”—people like Richard Dawkins. They’re generally very rational when it comes to arguments about God and his existence. But they’re still importing the whole of Christian ethics, treating that as an unquestioned floating axiom, and never integrating ethics into a rational worldview. You’ve written a book, In Good Faith, which is about leaving religion, a sort of fictionalized version of the story you’ve just told. Can you tell me a bit about why you decided to write that and why people might want to read it?

Hagerup: Well, it’s very much based on my own experiences in that time when I first moved to London. In the real world, I came with my then-wife. I’d just married her, which may sound strange because previously I said I’m gay, but that was part of how, in the world of religion, you have to suppress your true self and live according to the rules and regulations of that religion. So, I married a woman. But in the book, I don’t tell that full story because that would just be too complicated. So, in the story, it’s a young man who comes on his own to London to study the Bible at this great big church where everything is happening; there’s a big revival going on. And in the process, he finds out that a lot of things are not quite as they’re cracked up to be. So many of the stories that I tell in this book are absolutely based on real stories, to the point where I’ve had people contact me in the intervening years to say, “I just saw myself on every page.” A lot of people have experienced the same, and a lot of people have felt that they were going crazy trying to live according to what they believed was right. And of course, it’s a system ripe for abuse because you are supposed to be obedient to your leader. You are supposed to believe that even if he has faults and errors, he’s trying to serve God; he’s trying to do his best. So, in the overall interest of the church, you cover up, cover over the cracks, and you just turn a blind eye to terrible abuses of power and of people’s minds.

So, all of that I tried to tell about in this book. Although the book finishes on a somber note, it is, I think, one that has the promise of intellectual honesty. It’s a point where you notice that the protagonist has come to realize something about the world and that he can start from a more realistic point of view to reassess his life and his faith. For me, writing it was a process of catharsis. I had all these experiences weighing down on me since leaving the church and the faith. And it was almost like a cork in my mind that I just had to pull out to release creativity in other areas. I wrote it longhand using my fountain pen. I worked in London at the time, and every morning on the train, I would write, and coming back, I would write. And then over the weekend, I would get up early and type it all into my computer. So, it took quite a while to put it all together, but I had to get this off my chest; and in the process, I’m glad to say it has also helped other people.

Walker-Werth: Wonderful. William, that’s been really interesting. Thank you so much.

Hagerup: Thank you very much.

You can listen to the rest of this interview on YouTube.

This article appears in the Fall 2025 issue of The Objective Standard.

Support our work by upgrading your TOS subscription to Standard Bearer:

I saw Julia Sweeney’s one-person play, “Letting Go of God” years ago. Towards the end of the play, she finally is comfortable with no longer believing in God and is delighted that God is not monitoring her thoughts.