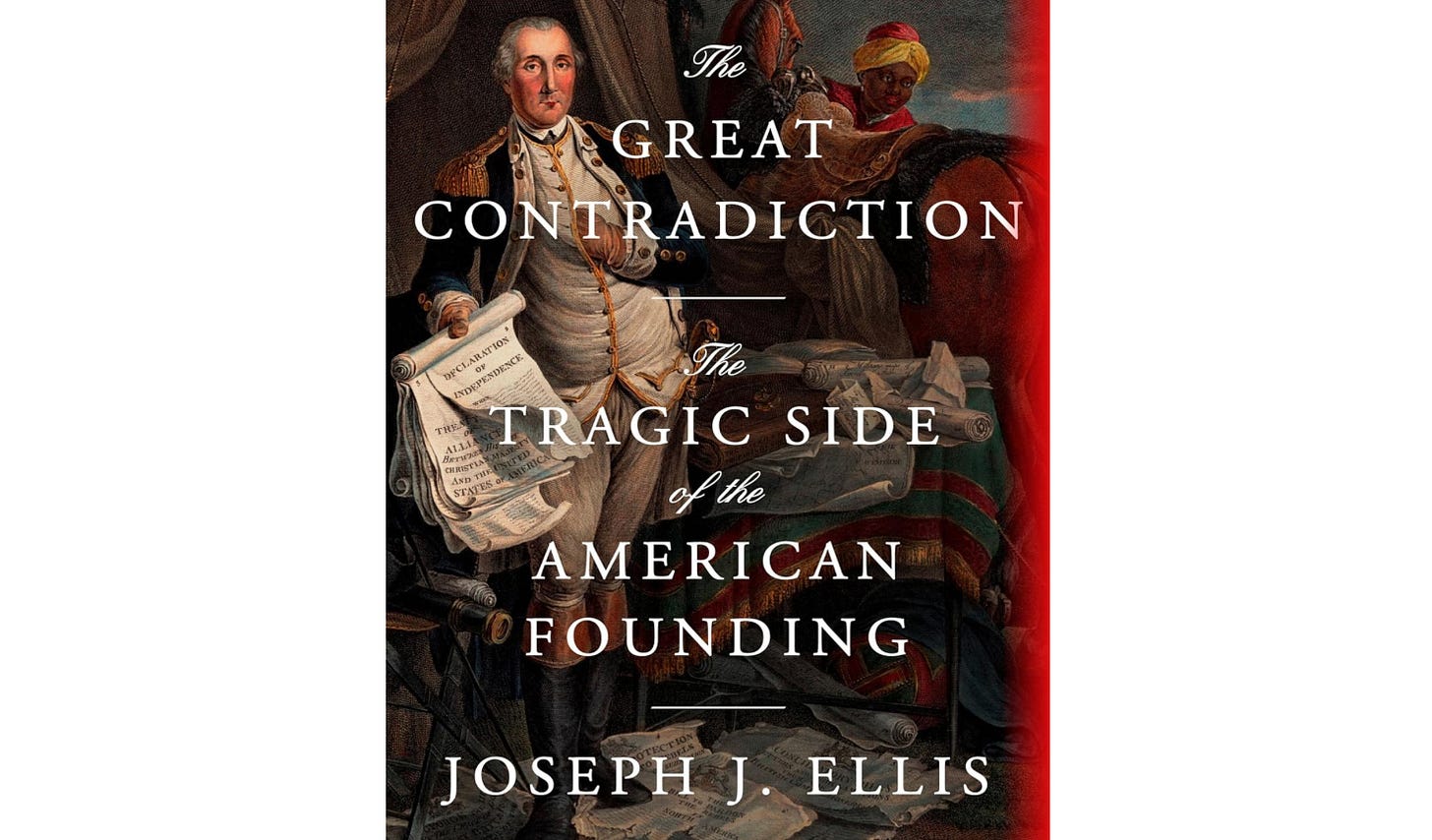

The Great Contradiction: The Tragic Side of the American Founding by Joseph Ellis (Review)

Reviewed by Timothy Sandefur

New York: Knopf, 2025

226 pp., $31

It’s clear from The Great Contradiction: The Tragic Side of the American Founding that Joseph Ellis is bothered by the scorn recently heaped upon the American founding fathers by writers such as those affiliated with The New York Times’s “1619 Project.” The Pulitzer Prize-winning historian opens his new book with a condemnation of those who treat the founders as little more than “trophies in the ongoing culture wars” and an appeal to readers to seek instead what he calls “historical truth in its most disarming configurations” (18, 19). The first step in that pursuit, as he sees it, is to avoid the “sin” of “presentism”—which means the tendency to look at the past with the condescending assumption “that our political and moral values now are wholly reliable standards of truth and justice for the assessment of our predecessors then” (18). Instead of damning the revolutionary generation as “a cast of despicable villains who collectively comprise the deadest, whitest males in American history,” or lionizing them as “demigods who were permitted to glimpse the eternal truths,” Ellis thinks we should see them as real, fallible people, confronted by complicated challenges (18, 15).

That may sound like a welcome respite from the activist, revisionist attitude that now dominates the history profession. It certainly seems more objective. But in reality, the picture Ellis offers—in which the founding is an “epic” that “defies all moralistic categories”—turns out to be a cure worse than the disease (14). That’s because beneath his pose of detachment, one finds a moral cynicism every bit as “presentist”—and as indefensible—as the assumptions of those he sets out to refute.

Consider his 1996 book American Sphinx, in which he wrote that the “mental universe” of the American founding “has changed so dramatically, [and] modern science has so unmoored all the ‘fixed principles’ that [the founders] took for granted, that any direct connection between then and now must be regarded as a highly questionable enterprise.”[1] In other words, the “self-evident truths” for which the revolutionary generation pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor aren’t really true—note the scare quotes around “fixed principles”—and cannot be, because there are no “eternal truths.” According to Ellis, when Thomas Jefferson and others said there were, they were just expressing a now-obsolete superstition—or dishonestly concealing their true motivations, which were more mercenary.

So, too, in his 2004 biography of George Washington, Ellis scoffed at the founders’ classical liberalism as “the grand illusion of the age” and maintained that the father of his country was guided not by principles of freedom but by more “elemental”—that is, materialistic and appetitive—drives. In fact, the word “elemental” appeared eighteen times in that book, as Ellis strove to prove that Washington’s true lodestar was not a belief in liberty and equality but an almost instinctual desire for financial and political power. “Economic rather than moral considerations,” he wrote, “seemed to weigh more heavily on [Washington’s] mind.”[2]

Not only is this false, but Ellis’s refusal to take the American revolutionaries’ moral assertions seriously is itself a modern conceit—a form of “presentism” that cripples any effort to understand the founders, let alone defend their integrity. Any objective evaluation of the Revolution must begin by asking whether the Declaration’s “self-evident truths” actually are true. Instead, Ellis offers a sort of implicit relativism that is itself an advent of the early twentieth century. It was then that scholars of history for the first time decided that their profession is (in the words of the influential philosopher of history Herbert Butterfield) “interested in the way in which ideals move men and give a turn to events rather than in the ultimate validity of the ideals themselves.”[3] It’s no coincidence that academic historians’ embrace of this allegedly “scientific” moral neutrality coincided with the academic philosophers’ rejection of the Aristotelian-Lockean principles underlying the American Revolution and their embrace of the Hegelian-Marxist view that morality and politics are functions of history, culture, and class struggle. In short, dismissing the Revolution’s moral and political premises as outdated irrelevancies—and viewing the founders as motivated by “elemental” economic considerations—is every bit as “presentist” as the critiques offered by the “1619 Project” and leftist academics.

This fatal philosophic defect in Ellis’s approach is dramatically worsened by what the jacket copy on The Great Contradiction calls his “flair for irony and paradox” but would be more accurately described as exaggerations, inaccuracies, self-contradictions, and downright falsehoods, as well as plain laziness. (Many paragraphs of this book, and even whole pages, are copied verbatim, without acknowledgment, from his previous volumes.)[4]

As for errors, they range from the relatively minor to the important and even shocking. Among the minor ones is his misquotation of a 1776 letter in which John Adams denounced provincial legislatures for attempting “ridiculous projects.”[5] Ellis misquotes this as “radical projects” and uses it to substantiate his claim that Adams was so devoutly conservative that he thought the revolution “meant nothing less than American Independence, but also nothing more” (35). That isn’t true, though. Adams was conservative in some ways—and became more so during George Washington’s presidency—but he was perhaps the most radical member of the Second Continental Congress. It was he, for example, who drafted the resolution calling on colonial legislatures to overthrow their governments and start from scratch.

A more important error occurs in a passage in which Ellis says the revolutionaries “ignored altogether” the Declaration’s famous “we hold these truths” paragraph (43–44). That’s nonsense. As Pauline Maier and other historians have shown, those truths were both articulated and embraced throughout the colonies; they were anticipated and reiterated in documents as grandiose as the Virginia Declaration of Rights and as humble as the resolutions adopted by members of trade unions.[6] Far from being ignored, they were printed and reprinted across America, and they led—as Gordon Wood proved in The Radicalism of the American Revolution—to a total transformation of American society after independence was established.[7]

As for shocking errors, perhaps the worst comes in the midst of Ellis’s discussion of white people’s attitudes toward blacks in the mid-1770s. He quotes a newspaper article that said blacks “are not fully human” and that God created them “for the benefit of the White people” just like “Horses, oxen, [and] dogs” (31). Such racism is mortifying indeed and would fit right in among the ravings of nineteenth century “fire-eater” secessionists—but it was startling and unusual in the mid-1770s, before the pseudoscience of racism took off in America. What explains this anomaly? It turns out that the article Ellis is quoting is well known to have been a hoax—a satire that some scholars have even attributed to Benjamin Franklin, who often mocked the institution of slavery.[8]

The reason Ellis fails to recognize it as a satire is simple: He cannot bring himself to believe that the founding generation could truly have thought that all men are created equal and that slavery was wrong. This also leads him to dismiss efforts by Virginia lawmakers in the 1770s to restrict the slave trade (as well as the 1775 resolution by the Continental Congress to forbid it) as motivated “by realistic political calculations” as opposed to “moral considerations,” which, he says, “had no role to play in [their] deliberations” (34). That, too, is false. In reality, many Virginia leaders considered slavery a colossal evil long before the Revolution and sought to shut down slave importation as a first step toward destroying the practice itself. That may have been naive, but it was motivated by genuine principle—as Ellis himself admits only pages later when, in one of his characteristic self-contradictions, he quotes contemporaneous Virginians who denounced slavery as “incompatible with the glorious struggle America is making for her own Liberty” and acknowledges that the revolutionary leaders “stigmatized any and all institutions based on coercion rather than consent” (37).

An even more glaring example of Ellis’s confused and confusing approach to these issues comes in his discussion of the famous paragraph Jefferson wrote for the Declaration of Independence denouncing King George for promoting slavery (which Jefferson called a “cruel war against human nature itself”). Jefferson was frustrated for the rest of his life by his colleagues’ decision to remove this from his draft before adopting the Declaration.

The passage referred to efforts by several colonies (including Virginia in 1710, 1727, 1766, and 1770) to ban or limit slave importation—efforts King George and his predecessors had blocked. After nixing the last of these, George ordered all colonial governors to veto “any [future] laws whatever . . . by which the importation of slaves shall be in any respect prohibited or obstructed.”[9] Then, when the war broke out, his deputy in Virginia, Governor Dunmore, sought to suppress the revolution by proclaiming that slaves owned by rebels, and who were “able and willing to bear arms” against the Americans, could join the British army and be freed. This was plainly no abolitionist undertaking—anybody enslaved by a Loyalist was ineligible, as were women or others unable to “bear arms.” Instead, it was an attempt to terrorize white Virginia Patriots with the very real specter of race massacre.

Thus, Jefferson sought to indict George and his deputies for prohibiting Virginians from clamping down on slavery while at the same time encouraging enslaved Virginians to rise up and slaughter colonists—a horrific tactic that well deserved Jefferson’s eloquent rebuke: “[The king is] paying off former crimes against the liberties of one people with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.”[10]

But Ellis characterizes Jefferson’s paragraph on slavery as “incoherent” and “preposterous” (41–42). He claims that it was self-contradictory to condemn Dunmore for “offering freedom . . . to all runaway slaves” while simultaneously denouncing slavery as a “cruel war on human nature,” and he ridicules the idea that the British government had “impose[d]” slavery on “unwilling colonists” (49, 43). “None of [Jefferson’s wording] made rational sense,” he concludes (42).

That gets it backward. First, Dunmore’s proclamation did not offer freedom to all runaways—only to those belonging to rebels who were able to bear arms. Second, although some colonists were blameworthy for buying and keeping slaves, the British government certainly did “impose” the practice on them by forbidding them from taking steps to limit it. Finally—and most importantly—there’s nothing at all inconsistent in condemning both the institution of slavery and the British government’s cynical effort to manipulate the enslaved by offering freedom as an incentive to murder their masters. If anything, it was Dunmore who acted inconsistently, by liberating a particular group of slaves in an effort to perpetuate the institution of slavery in America.

Still, the book’s most extraordinary—and revealing—flaw is probably Ellis’s astounding claim that the revolutionaries “ignored altogether” the Declaration’s paragraph about self-evident truths, and that this enabled Jefferson to “smuggle, in plain sight, the core principles of the natural rights philosophy into the [Declaration]” (41). Not only is this false, but it’s hard to imagine how such “smuggling” could even occur. To begin with, the “core principles of the natural rights philosophy” were common currency among American Patriots, who quoted and cited them in hundreds of declarations, resolutions, petitions, and pronouncements dating back at least to 1772, when the “Boston Pamphlet” (a lengthy publication overseen by Samuel Adams) opened with an eight-page disquisition on natural rights philosophy that even cited John Locke by name. Two years later, the First Continental Congress debated for days whether to base their argument for American self-rule on natural rights philosophy—and concluded in the affirmative. So, by 1776, no “smuggling” was necessary.

Nor was it possible. The Declaration was one of the most meticulously edited documents in American history. Jefferson’s wording was reviewed and edited by Benjamin Franklin (one of the country’s most celebrated writers), John Adams (among its most prolific), and fifty-three other delegates at the Continental Congress—many of them skilled lawyers—who spent two days correcting even Jefferson’s grammar. The idea that the Virginian somehow “smuggled” into the Declaration a concept as profound as “all men are created equal” is laughable.

Equally ridiculous is Ellis’s claim that this “smuggling” succeeded because “most delegates were fixated on . . . their rights as Englishmen” rather than the principles of natural law (43). Actually, although the traditional “rights of Englishmen” played a central role in the controversy between colonists and the mother country, by July 1776 Americans had abandoned their efforts to lay claim to those rights. Parliament, after all, had spent more than a decade refusing even to read petitions asserting their “English rights,” and in the 1775 Prohibitory Act, it declared Americans to be outside the King’s protection. The whole point of the Declaration, therefore, was to assert that the colonists were no longer Englishmen and consequently, were no longer asserting “English” rights. Instead, they regarded themselves as a separate nation and asserted their human rights.

Even aside from these profound flaws, however, The Great Contradiction fails to offer any meaningful answer to the contemporary critique of the founding. The reason is Ellis’s refusal to grapple with the Revolution’s philosophic core. This leaves him unable to offer any reply to the “1619 Project” except for a self-defeating refusal to apply what he calls a “morally correct approach” to the history of America’s founding (94). “No [Constitution] that met our modern-day standard of social justice,” he claims, “could ever have been passed or ratified” (94). Whether that’s true or false, it’s simply no answer to those who say that the Constitution that did get ratified was a “white supremacist” document.

In fact, it’s a kind of concession. After all, the moral and political issues at stake in historiography of the American Revolution are critical precisely because the Declaration speaks of truths, not myths; of principles that, if true at all, are always and everywhere true. And the reason the debate over America’s founding preoccupies us so much is because that debate isn’t really about whether the founders did the right thing in their day. It’s about whether they deserve our admiration in ours—and whether their legacy remains worthy of being preserved, protected, and defended. The answer is “yes” but for the very reason Ellis rejects: Far from “defy[ing] moralistic categories,” America’s founders made unprecedented progress toward the liberation of the human race from the tyranny and ignorance in which it had languished for so long (14). This is an objectively good thing, and the founders accomplished it because they did, however imperfectly, “glimpse the eternal truths” (15). To defend or even to comprehend that feat, however, requires abandoning the “presentist” pretense of moral neutrality.

This article appears in the Winter 2025 issue of The Objective Standard.

[1] Joseph J. Ellis, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Vintage, 1998), 353.

[2] Joseph J. Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (New York: Vintage, 2004), 258.

[3] Herbert Butterfield, The Whig Interpretation of History (New York: Norton, 1965), 67.

[4] To cite just a few examples, compare page 15 with page 17 of American Creation (New York: Knopf, 2007), page 135 with pages 214–15 of American Creation, page 148 with page 238 of American Creation, page 164 with page 147 of American Creation, page 129 with page 119 of Founding Brothers (New York: Vintage, 2000), or page 185 with page 42 of American Dialogue (New York: Knopf, 2018). Ellis claims that The Great Contradiction “was written in longhand with a five-point rollerball pen in my study,” but if so, he must have a photographic memory (193).

[5] Robert J. Taylor, ed., The Adams Papers, vol. 4 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), 332.

[6] Pauline Maier, American Scripture (New York: Knopf, 1997).

[7] Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Knopf, 1991).

[8] Winthrop D. Jordan, “An Antislavery Proslavery Document?,” Journal of Negro History 47, no. 1 (January 1962): 54–56; Kendra Asher, “Interpretations of Hume’s Footnote on Race” (October 17, 2020), 35–36, available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3713919 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3713919.

[9] Leonard Woods Labaree, ed., Royal Instructions to British Colonial Governors 1670–1776, vol. 2 (Octagon Books, 1967), 679.

[10] Merrill Peterson, ed., Jefferson: Writings (New York: Library of America, 1984), 22.

Ellis didn’t start as a disappointment, but he has become one.

At the conclusion of the Constitutional Convention on September 17, 1787, this arrogant contemporary (me!!) imagines himself - in addition to the fifty-six representatives invited from the colonies, present as well. This imagined fifty-seventh Representative has been recognized by the Chair to address the collection of delegates. Delegates who perhaps represent the greatest gathering of enlightened political thinkers of the time. He would argue, at any time, in history.

He has been inspired by their intelligence, sobered by their intellect - and has developed a reverence for their resolute determination as they resolved issue upon issue impeding their progress toward their goal.

As he is recognized and rises to speak, his manner is somber and reserved – unusual for such an arrogance.

“Gentlemen (there were no women present. Additionally, it would be quite a while before the ideals expressed in Mr. Jefferson’s profound Declaration would politically include women, black Africans, and Native Americans): The political institutions you envision and have remarkably fashioned, do not have the moral foundation to secure the ideals stated in Mr. Jefferson’s unprecedented Declaration.

Specifically, one cannot argue on behalf of a human being’s political right to their own life, creating political institutions designed, debated, and adopted to then secure same, while at the same time accepting of a morality that a human being has a universal higher moral obligation. One that demands they live their life in service to some other purpose not of their choice - either to other human beings, or an imagined greater entity or abstraction.

Those for whom you wish to politically-secure such a right, and from whom its recognition and respect must be understood and defended, will disagree with it, while they maintain that each among us has a “higher” moral duty to fulfill, one that makes the “right” to one’s own life subordinate.

This tirelessly repeated moral prescription has destroyed whatever expression of an individual’s right to their own life (individual responsibility and the rights required for its exercise!) as may have been temporarily recognized in past societies, without exception. In the absence of a proper moral defense of them, this body’s unprecedented attempt at their political consecration shall become doomed as well.” – David Walden, August 12, 2005.

Dave