Independently published

369 pp, $28

The twentieth century’s most destructive ideology is now the least understood. Across Europe, America, and parts of the Global South, support for socialism and communism is making a comeback. A striking number of young people in the West now view these systems favorably, often attributing their past failures to poor implementation.[1] In many developing countries, too—ironically, those most desperately in need of free markets—socialism is widely regarded as morally superior to capitalism.

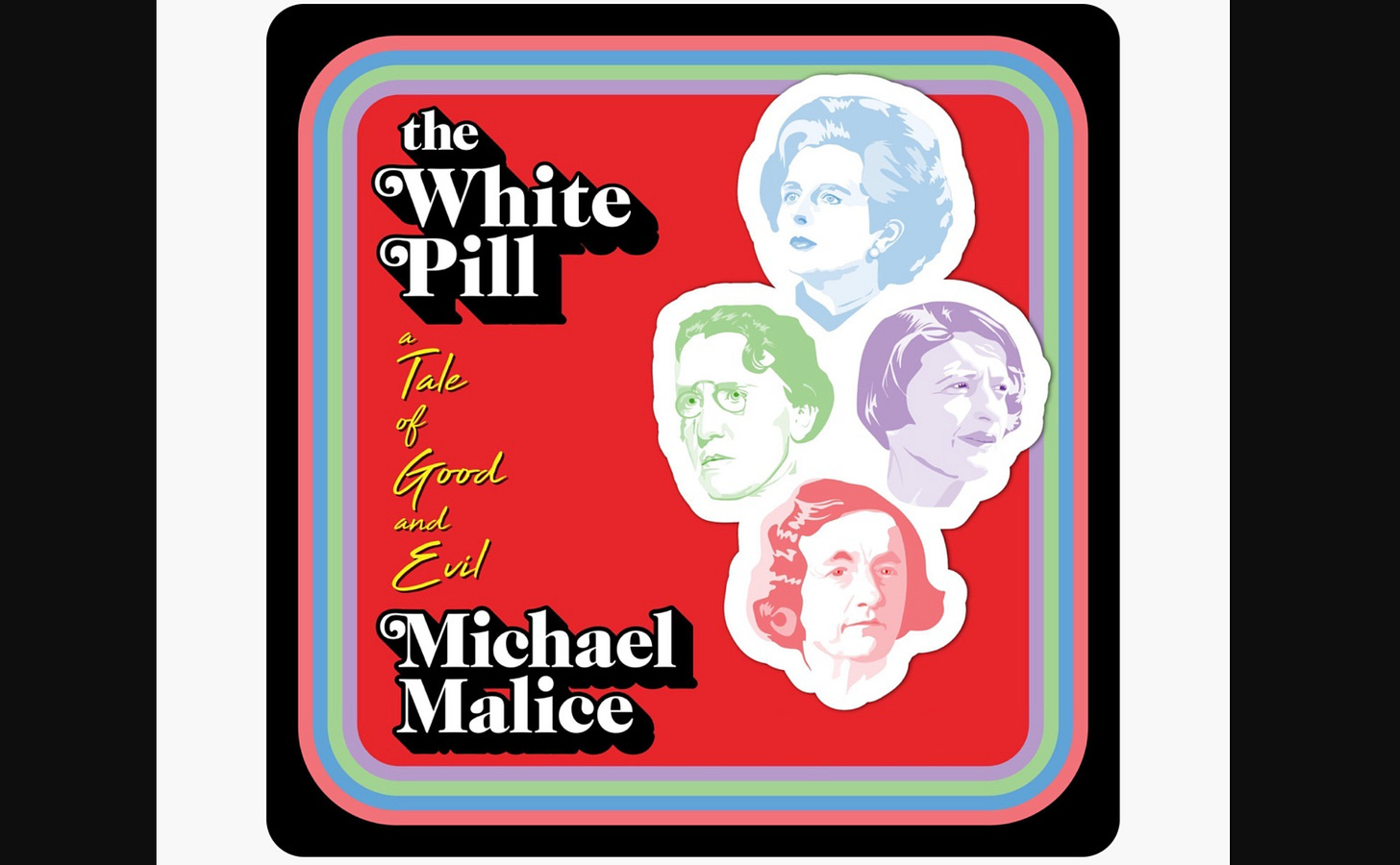

Much of this fascination rests less on conviction than on vague altruistic aspirations held without a grasp of what these systems required or produced. Few of socialism’s defenders can define its principles, much less account for its record. This blind belief persists largely because the history of twentieth-century communism is no longer well understood. Michael Malice’s The White Pill: A Tale of Good and Evil is an accessible introduction to the history of Soviet totalitarianism that addresses this knowledge gap. Malice condenses nearly a century of communist history into an engaging narrative, exposing the logic and policies behind its rule. The book follows the Soviet state from its rise and expansion into central and eastern Europe to its eventual collapse. Through chilling details, Malice clearly shows what it meant to live under that system and how many in the West refused to see that reality.

Malice begins his story in 1947—not in Petrograd or Moscow but in a congressional hearing room in Washington, D.C. He opens with the testimony of Russian-born writer and philosopher Ayn Rand, who had fled the Soviet Union two decades earlier. She was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee to comment on Song of Russia, a wartime film that portrayed Stalin’s Soviet Union as a cheerful paradise.

Rand dismissed the film as irrelevant. Her concern, she explained, was not with one piece of propaganda but with a broader failure to grasp the nature of totalitarianism. She addressed the casual willingness to promote falsehoods about a regime that she had witnessed personally to be radically antithetical to human life. Her account of life in Soviet Russia—the fear, the isolation, the routine of brutality—captured the essence of life under that system but was met with skepticism. Treating her testimony as no more than a personal impression, Congressman John McDowell asked what appeared to be a sincere question: “That is a great change from the Russians I have always known, and I have known a lot of them. Don’t they do things at all like Americans? Don’t they walk across town to visit their mother-in-law or somebody?” (loc. 238). Malice places Rand’s response at the center of his narrative:

“It is almost impossible to convey to a free people what it is like to live in a totalitarian dictatorship. I can tell you a lot of details. I can never completely convince you, because you are free” (loc. 248).

Rand’s answer, as Malice shows, anticipated the pattern of skepticism that followed even the clearest warnings about Soviet brutality. Through facts, personal stories, and the logic of the policies carried out over decades, he illustrates the immense human suffering under the brutal rule of that system.

Beginning with the Bolshevik rise to power under Lenin, he clearly describes the sweeping decrees, institutions, and rise of terror as a deliberate policy, executed exactly as intended. The earliest of Lenin’s decrees nationalized private property, placed production under state control, and outlawed dissent. Though Marx had envisioned a state that would eventually “wither away,” Malice notes that Lenin envisaged his “dictatorship of the proletariat” as “one ‘maintained through violence’ and ‘a power unbound by laws’” (loc. 725).[2]

Malice thus effectively challenges the historical revisionism that survives today: the notion that Lenin’s violence was justified, unlike Stalin’s arbitrary excesses—that Lenin was a principled revolutionary and Stalin the dictator who corrupted his legacy. Years before 1917, Lenin endorsed torture and political repression as tools of control, legitimizing force in the eyes of the party as the future regime’s central mode of governance.

In Stalin’s hands, the ideological foundation that Lenin laid became the basis of mass repression on an unprecedented scale. Malice shows how Stalin continued to weaponize the “logic” of class warfare through relentless propaganda. Kulaks—the relatively rich farmers—were vilified as saboteurs and parasites, blamed for famine. The same “logic”—that socialism would work without “selfish” exploiters—was applied to explain away every policy failure. According to the Soviets, Malice explains,

As the Kulaks were to blame for issues with food and agriculture, so too emerged a class of invisible foes responsible for problems of industry: the wreckers. Because the Soviet system was a perfect one and the ideology not just correct but scientifically correct, it logically followed that all industrial mistakes must be the result of sabotage by invisible, omnipotent wreckers. (loc. 1726)

Malice recounts the consequent horrors in relentless succession—mass starvation, torture, show trials, prison camps—capturing the scale of brutality under Stalin. He consistently ties this violence to crucial facts that expose the myths shaping today’s enthusiasm for socialism, such as Stalin’s antisemitic purges and his collusion with Hitler in suppressing the Nazi extermination of Jews in Soviet territory. Claims that Stalin’s crimes were less evil than Hitler’s—because they were motivated by “noble” egalitarian principles rather than hatred—collapse under the facts Malice presents, to say nothing of the implication that mass persecution in the name of class inequality is any less evil.[3]

One of the book’s most interesting takeaways is the extent to which Western intellectuals were complicit in furthering Soviet propaganda and sanctioning its power. Respected journalists, academics, and public thinkers rushed to deflect any serious criticism of the regime at every stage. Malice captures the disturbing attitude that considered no amount of horror too great a cost for the Soviet dream. Figures as prominent as Jean-Paul Sartre, Theodore Dreiser, George Bernard Shaw, and even American Vice President Henry Wallace—who personally toured the Siberian gulag town of Magadan—rushed to defend or excuse the regime. Malice’s shocking accounts of these defenses provide crucial insight into why the romantic reputation of these ideologies persists today: It has been shaped by decades of intellectual evasion.

Malice then turns to the fate of the Soviet regime after Stalin. He reveals how the ideology of control persisted even as Stalin’s “cult of personality” began to dissolve. “Stalin’s veneration began to be reversed. . . . In Prague there stood a gigantic fifty-foot-tall statue of Stalin leading a group of workers, one that took over five years to build. It was dynamited into nothing. Statue after statue, honor after honor, monument after monument—all began to fall” (loc. 3478).

The dismantling of Stalin’s cult, however, was purely political. Malice shows how the regime vilified Stalin as a “reactionary” to protect the system itself—the same argument we hear today from its defenders, who dismiss its brutality as a distortion of true socialism. The collapse of symbols did not mean the collapse of the system; Malice shows how its terror endured throughout its sphere of influence, most starkly visible in the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Escape attempts, surveillance tactics, and the Stasi’s atrocities defined life for more than a generation. For many readers, the crimes of the Nazi regime are rightly familiar. But the brutality of the communist GDR remains largely unacknowledged. What strikes deeply here is Malice’s emphasis that the Berlin Wall was not some relic of a distant past but a barrier that stood for decades in a European capital, dividing families, imprisoning a population, and spelling death for those who tried to flee; yet, like much else in the history of communism, it is treated as distant, if it is seen at all.

Malice honors two figures who played a decisive role in challenging the Soviet power: Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. In contrast to the evasions of earlier Western leaders who sought détente or accommodation with communist rule, Reagan and Thatcher treated communism as a moral evil. Malice presents their unapologetic stance as a crucial change from decades of Western compromise. Their clarity and conviction, Malice shows, hastened the collapse of what Reagan termed the “evil empire” (loc. 4528).

The White Pill makes for a compelling history and serves as an excellent introduction for readers unfamiliar with communism’s past. Malice’s style, however, dulls the narrative clarity and momentum at times. His casual, sarcastic tone, which is often amusing, is overdone. He expands on topics of personal interest that do little to advance the narrative. His entire chapter on the history of anarchism in America, biographical tangents, and detours into Thatcher and Reagan’s personal lives and careers are distracting—though some are interesting in themselves.

These choices could reflect Malice’s own intellectual background. He describes himself as an “anarchist without adjectives” and often speaks about his interest in Objectivism, anarchist thought, and history of totalitarianism. Although his grounding in history and philosophy gives The White Pill much of its moral clarity, his frequent tangents about these influences make the book difficult to take in as a whole. Nevertheless, The White Pill still succeeds as an engaging introduction to the history of Soviet communism.

Malice’s central point is that the Soviet empire, for all its power and reach, was defeated. That outcome represents the White Pill: a rejection of nihilism, not in the sentimental sense of being optimistic but as a conclusion from facts of history that evil is not inevitable and that it can be overcome.[4] Malice writes,

Within ten years, the Soviet Union went from being a perpetual world-dominating superpower to literal non-existence and is now becoming a forgotten chapter of world history. . . . But Ayn Rand was right: this was no laughing matter. Millions of people were trapped for decades in countries where human life was nothing, less than nothing, and they knew it. (loc. 5921)

But the defeat of that system did not bring the moral clarity it should have. The horrors of the Soviet regime are now treated as distant history, unconnected to the ideology that made them possible. The White Pill brings that history back into view and shows us why it is important to remember it.

This article appears in the Winter 2025 issue of The Objective Standard.

[1] Michael Chapman, “Young Americans Like Socialism Too Much—That’s a Problem Libertarians Must Fix,” Cato at Liberty, May 15, 2025, https://www.cato.org/blog/young-americans-socialism-too-much-thats-problem-libertarians-must-fix; Institute of Economic Affairs, “67 Per cent of Young Brits Want a Socialist Economic System, Finds New Poll,” July 6, 2021, https://iea.org.uk/media/67-per-cent-of-young-brits-want-a-socialist-economic-system-finds-new-poll.

[2] “Withering Away of the State,” Wikipedia, last modified September 20, 2025, accessed September 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Withering_away_of_the_state.

[3] Julie Burchill, “Fascism Bad, Communism Good(ish),” The Guardian, October 30, 1999, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/1999/oct/30/weekend.julieburchill?u;

Kenny Conor, “A False Equivalency—Comparing Stalin to Hitler,” University Times, March 8, 2012, https://universitytimes.ie/2012/03/a-false-equivalency-comparing-stalin-to-hitler.

[4] John Stossel , “Capitalism Is the Antidote to ‘Black-Pilled’ Internet Pessimists,” Reason, December 18, 2024, https://reason.com/2024/12/18/capitalism-is-the-antidote-to-black-pilled-internet-pessimists.