Author’s note: This review contains spoilers.

If you’re a fan of deep, thoughtful dystopian fiction—or of thoughtful, intense science fiction—then you should check out a little-known 1980s TV phenomenon. Its name is simply V.

Loosely inspired by Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 dystopian novel It Can’t Happen Here, which projected a fascist takeover of America similar to Hitler’s then-recent takeover of Germany, the original 1983 V miniseries begins with the arrival of a fleet of alien spacecraft over Earth’s major cities. The aliens, who call themselves “Visitors,” offer to solve many of humanity’s medical, technological, and ecological challenges in return for our help in producing a chemical compound they can’t produce at home. The United Nations readily agrees, and hordes of Visitors—who look just like us but have distorted voices that hint at their truly alien nature—begin to arrive in cities across the globe. Some people welcome the Visitors, some reject them, and some don’t know what to think.

Across the original miniseries and the 1984 follow-up, V: The Final Battle, we see how several dozen key human and Visitor characters resist, enable, and execute the Visitors’ plans. We follow human rebels and collaborators, and their family members, as well as various factions within the Visitors. As the story unfolds, we gradually learn the truth about the Visitors’ nature and intentions. And we discover, along with the characters, how precious freedom is as the Visitors and their human collaborators begin to take control of businesses, airwaves, governments, and police forces.

The way the Visitors impose their dystopian rule on Earth has many parallels with the Third Reich, in part thanks to the influence of It Can’t Happen Here. For example, soon after their arrival, the Visitors set up a “Friends of the Visitors” youth organization clearly modeled on the Hitler Youth. Even the Visitors’ flag more than passingly resembles a swastika. Later in the miniseries, the Visitors begin to demonize and round up Earth’s scientists, the people most able to identify and resist their plans. When a scientist and his family come to his friend Stanley Bernstein’s house looking for a place to hide, Stanley’s father, Abraham—an elderly Jewish man who had escaped the Holocaust—passionately advocates to his son that they should take in the runaway scientist and his family:

Abraham: We had to put you in a suitcase. In a suitcase! You were eight months old. That’s how we smuggled you out.

Stanley: I know the story!

Abraham: No, you don’t! You don’t. Your mother, auv shalom . . . your mother didn’t have a heart attack in the boxcar. She made it with me to the camp. I can still see her, standing naked in the freezing cold. Her beautiful black hair was gone. They’d shaved her head. I can still see her waving to me, as they marched her off with the others to the showers—the showers with no water. Perhaps, if somebody had given us a place to hide . . . don’t you see, Stanley? They have to stay. Or else, we haven’t learned a thing!

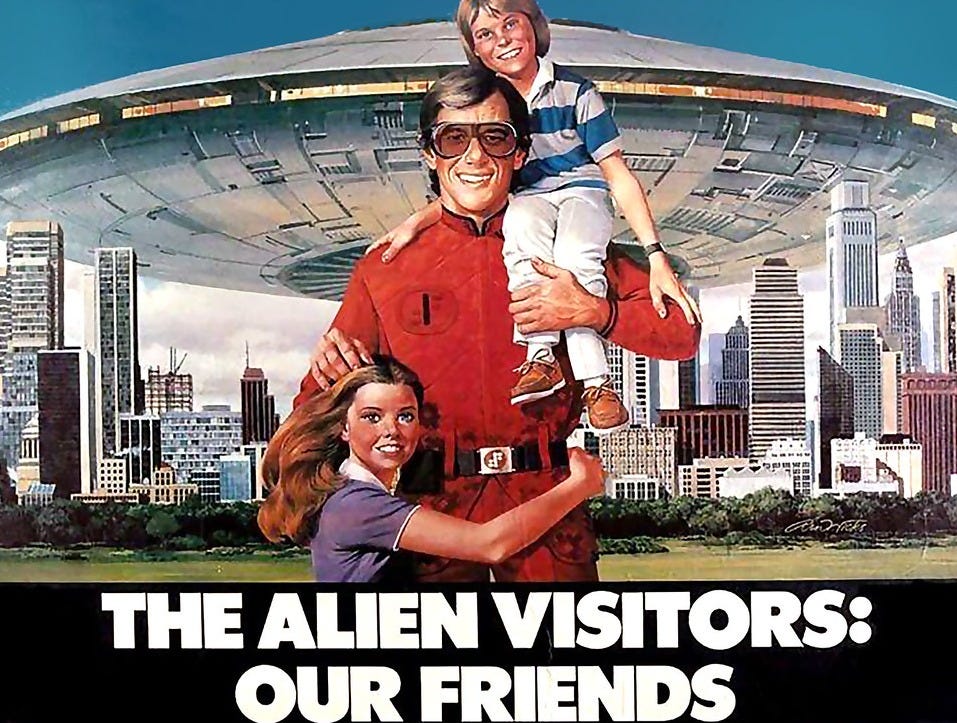

The propaganda that the Visitors use is also heavily reminiscent of Nazi propaganda. They force governments and businesses to put up posters everywhere that prominently feature the heroic-looking Visitors helping the people of Earth in a fatherly manner (which the rebels deface with a red “V” symbolizing the victory sign that Winston Churchill popularized during World War II). They also distribute their propaganda over the airwaves with the help of Kristine Walsh, a journalist who voluntarily becomes the Visitors’ primary public face.

The second miniseries also features a powerful exchange between Mike Donovan, a leader of the rebellion, and his mother, Eleanor, a status-chasing collaborator with the Visitors. She dismisses his claims that the Visitors are suppressing human freedom, telling him, “Those of us who respect law and order are free. It’s criminals like you that cry fascist.” In response, he argues, “You’re just as free as the leash you’re on. You tug it too hard—they’ll strangle you with it.”

Much of both miniseries’ storytelling power comes from the rich character dynamics that tie directly into the broader conflict, such as the relationship between Mike and Eleanor. Another heart-wrenching example is the story of Robin, a teenage girl who gets into a romantic relationship with one of the Visitors, despite already having a human boyfriend and despite her family being involved with the resistance. Robin becomes the center of a web of manipulation stretching from the Visitors’ commanders to the heads of the resistance.

Throughout the story, we see characters who stand firmly for freedom, others who wilfully collaborate in pursuit of status and power, and still others who try to evade the reality of the situation until it leaves them with no choice. All those decisions come with consequences, something V’s creators were never afraid to show explicitly; although the series isn’t especially graphic, it’s frequently shocking in the effect the people’s actions have on the lives of others.

At its core, V is a series about rebellion against tyranny. Both episodes of the 1983 miniseries open with the message, “To the heroism of the Resistance Fighters—past, present and future—this film is dedicated.” The show spends a great deal of time probing the question of what actions are and are not appropriate to take in the cause of overthrowing tyranny. Many of the rebels readily suggest sacrificing innocent people for the cause or testing new weapons on captured Visitors (including one who is helping the resistance), while others argue passionately for the value of each life and the importance of clear moral principles.

Although both V miniseries are outstanding works of dystopian fiction, the final moments of V: The Final Battle include a scene that falls well short of the standards of the prior episodes. In it, an imminent threat is resolved by deus ex machina—the sudden intervention of a super-powerful character with virtually no prior setup or explanation of how she got her power. This was unfortunately a sign of things to come, as original V writer and producer Kenneth Johnson had left the series during production of The Final Battle following conflicts with the studio and was not involved in the subsequent short-lived weekly V series, which doubled down on this story line. Had this scene been changed to make the resolution the result of the rebels’ and Visitors’ choices and actions, as is the case with the rest of the story, the two miniseries would be close to perfect. Nonetheless, they remain one of the strongest works of dystopian sci-fi TV I’ve seen.

V has influenced many subsequent works. Fans of Independence Day (1996) will find the visuals of gigantic alien saucers hovering over major world landmarks suspiciously familiar. (The visual effects in V vary in quality—many shots of Visitor ships hovering over major cities are breathtaking, but many of the scenes involving moving spacecraft are poorly superimposed and have aged badly.) Likewise, fans of John Carpenter’s 1987 classic They Live will identify several points of commonality between V and that movie. And well-versed sci-fi fans will see how V directly inspired elements of several later science-fiction series, including The X-Files, Babylon 5, and Earth: Final Conflict.

V and V: The Final Battle are arguably essential watching for any fan of dystopian fiction or science fiction. They are a sadly under-recognized landmark in science-fiction history, and they demonstrate that the American spirit of freedom and individualism was alive and well in Hollywood in the early 1980s. It’s a spirit that’s extremely rare and often actively undermined in modern cinema, so if you’re ever looking for a show that conveys the importance of fighting for freedom in a principled and captivating way, this is the show for you.

This article appears in the Fall 2025 issue of The Objective Standard.