Author’s note: This is the second of three articles for The Objective Standard dealing with military history and its (in this case implicit) lessons for the modern day. The third article will consider the lessons of the American victory over Japan in World War II. These articles draw from my forthcoming book, Nothing Less than Victory: Military Offense and the Lessons of History from the Greco-Persian Wars to World War II (Princeton University Press).

Imagine that an asteroid is heading toward the earth at thousands of miles per hour. While it is still far away, a small force can change its direction a few degrees and avert a catastrophic collision. But as it moves closer to the earth, the force needed to divert it multiplies exponentially, until only a massive explosion can prevent disaster. It would be one thing if men did not know of the asteroid, or saw it coming and were impotent to act. But suppose they had the bombs and the rockets needed to deflect it—but refused to do so because of “international opinion,” a desire to spend the money on “social programs,” or a claim that we must not interfere in the comet’s own “natural” movements? This describes, in essence, Europe’s drift into World War II.

During the 1930s, men stood at a cusp in time, a point of momentous decision, watching the growing power of Germany under its screaming, malevolent leader. Their failure to confront Germany—and the devastating consequences of that failure—demonstrate the power of ideas, both to motivate aggressors and to undercut defenders from taking the actions needed to protect freedom.

On September 1, 1939, twenty years and nine months after the armistice of November 11, 1918, that had ended World War I, millions of Germans obeyed their Leader’s call for a war of national aggrandizement and launched a new slaughter across Europe. The attack on Poland was the climax of five years of military buildup by Germany, which had followed fifteen years of feverish international diplomacy, economic transfers, and political agreements. Most European leaders had worked fervently to avoid a new carnage. They fell prostrate before Hitler’s “Lightning War.” The deepest reasons why so many Germans joined the armies of the Nazis, hailed their leader, followed their orders, and drank to their war cannot be found in reasons as shallow as economic stagnation, political dissatisfaction, or bad feelings about the last war. These factors were present in many nations that did not attack. In essence, the Germans were in the grip of a philosophic pathology, a set of ideas that told them it was morally good to sacrifice themselves and others to the all-powerful State, the Race, and the Leader. The power of these ideas in German culture was expressed in the mass support that the Nazis enjoyed among “Hitler’s Willing Executioners.”1

But another force, outside of Germany, also pushed the world toward blitzkrieg and Auschwitz. This force too was a set of ideas—ideas in the minds of Germany’s opponents—which prevented England and France from confronting Hitler when they could. In the mid-1930s, British politicians in particular were restrained from action, not by an incapacity to act, but by a lack of will. Certain moral ideals—which rose to the cultural forefront after the horrendous experience of World War I—conditioned British politicians and their constituents to become virtual allies of Germany in its drive to regain its status as a powerful nation. The result was a paralysis in the western European nations, which disarmed them as surely as any bomb and allowed Hitler to build up his forces to the point where his ability to fight exceeded that of his enemies.

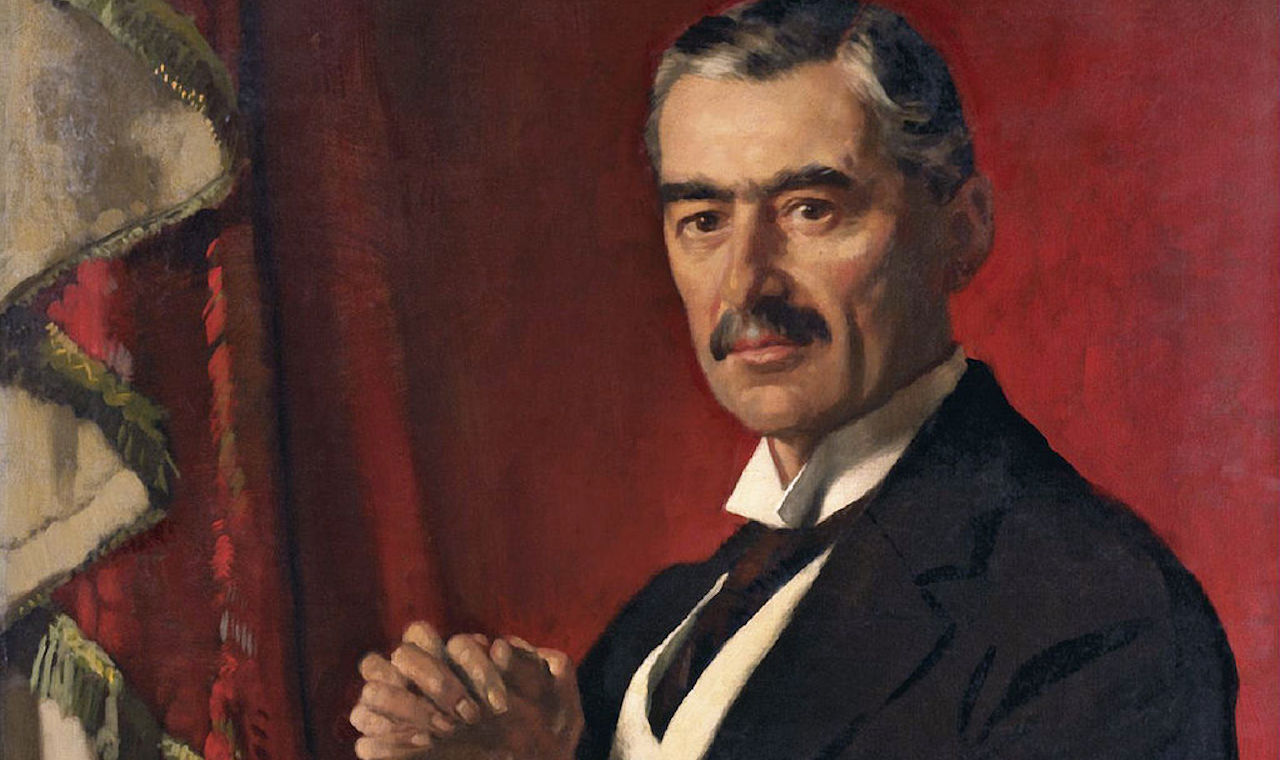

The appeasement of Germany by Britain in the late 1930s has become a synonym for weakness, focused on a single man: Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who claimed “peace in our time” by handing over Czechoslovakia to Hitler in September 1938. But Chamberlain’s appeasement, far from being a new, short-term plan by a weak man to deal with an emergency, was the culmination of a long policy that stretched back to World War I. The British desire for peace was conditioned by a set of moral ideas that hamstrung British leaders from recognizing the fundamental differences between their own nation and the German state, and the fundamental contradiction between the goals and policies promoted by leaders of the two nations. Those moral ideas gained cultural power in the aftermath of World War I. They sapped the will of the British people to oppose Germany when it was possible to do so, and left their leaders unable to take the steps needed to stop Germany from rearming. To understand how and why European leaders empowered Germany to rekindle the fires of war, we must unpack those moral ideas. . . .

You might also like

Endnotes

1 Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Hitler’s Willing Executioners (New York: Vintage, 1997). For fundamental ideas as the crucial factors in history, see Leonard Peikoff, The Ominous Parallels: The End of Freedom in America (New York: Meridian, 1993). (Robert Waite, The Psychopathic God: Adolf Hitler [New York: Basic Books, 1977] fails to explain why the Germans put a psychopath into power.)

[groups_can capability="access_html"]

2 Donald Kagan, On the Origins of War and the Preservation of the Peace (New York: Anchor, 1995), pp. 282–83.

3 For an overview of the conference, see William R. Keylor, editor, The Legacy of the Great War: Peacemaking, 1919 (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1998).

4 Woodrow Wilson, “Fourteen Points” Speech, Delivered in Joint Session of Congress, January 8, 1918, http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/fourteenpoints.htm.

5 Immanuel Kant, Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Essay (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1983), Section II, “The Law of Nations Shall be Founded on a Federation of Free States.”

6 Raymond Poincaré, Welcoming Address at the Paris Peace Conference, January 18, 1919, http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/parispeaceconf_poincare.htm.

7 The Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War and on Enforcement of Penalties, May 6, 1919, http://www.firstworldwar.com/source.

8 Versailles Treaty, June 28, 1919, http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/imt/menu.htm.

9 Overly, Road, p. 122, who also stresses the French preoccupation with avoiding the next German invasion.

10 Sally Marks, “1918 and After: The Postwar Era,” in The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered: A.J.P. Taylor and the Historians, 2nd ed., edited by Gordon Martel (New York: Routledge, 1999), pp. 23–24.

11 Richard Watt, The Kings Depart: The Tragedy of Germany: Versailles and the German Revolution (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968), chapter 16.

12 Kagan, Origins, p. 290, citing Immanuel Geiss. “The Outbreak of the First World War and the German War Aims,” in 1914, The Coming of the First World War, edited by Walter Laqueur and George L. Mosse (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), pp. 71–74.

13 Hitler’s speech to the Reichstag, reported in the Times of London, February 21, 1938, p. 9.

14 Richard Lamb, The Drift to War: 1922–1939 (London: W. H. Allen and Co., 1989), p. 71, emphasis added.

15 Ibid., p. 69.

16 Kagan, Origins, p. 386.

17 James T. Shotwell, What Germany Forgot (New York: MacMillan, 1940), p. 82.

18 John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (London: Harcourt Brace and Howe, 1920), pp. 5, 35–36.

19 Gilbert, Roots, p. 62.

20 Keynes, Economic Consequences, p. 225.

21 Richard J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin Press, 2004), p. 66.

22 Martin Gilbert, The Roots of Appeasement (New York: New American Library, 1966), p. 52.

23 Sally Marks, “The Myth of Reparations,” Central European History 11, 1978, p. 237; excerpted in Keylor, Legacy, pp. 156–67. Kagan, Origins, p. 292. J. M. Keynes, A Revision of the Treaty (London and Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1922/1971), p. 24 for the figure of 132 milliards.

24 Marks, “Myth,” pp. 243–55; Kagan, Origins, pp. 292–96.

25 Kagan, Origins, p. 281, sep. notes 19 and 20; Steven A. Schuker, “The End of Versailles,” in The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered: A.J.P. Taylor and the Historians, 2nd ed., edited by G. Martel (New York: Routledge, 1999), pp. 38–56.

26 Marks, “Myth,” p. 254; David Lloyd George, The Truth about Reparations and War Debts (New York: Doubleday, 1932).

27 Peikoff, Ominous Parallels, p. 216.

28 Lamb, Drift, p. 6.

29 Stephen Van Evera, “The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War,” in Military Strategy and the Origins of the First World War: An International Security Reader, edited by Steven Miller et al. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), pp. 66–69.

30 William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1959), pp. 418–22.

31 Marks, “Myth,” pp. 240–41, 248.

32 Marks, “1918 and After,” p. 29.

33 Final Protocol of the Locarno Conference, The Conference of Locarno, October 5–16, 1925, http://www.lib.byu.edu/~rdh/wwi/1918p/locarno.html.

34 Vittorio Scialoja, Sixth Assembly of the League of Nations, December 12, 1925.

35 Marks, “1918 and After,” p. 25.

36 Treaty of Rapallo, April 16, 1922, http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/intdip/formulti/rapallo_001.htm.

37 Treaty of Berlin between the Soviet Union and Germany, Berlin, April 24, 1926, http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/intdip/formulti/berlin_001.htm.

38 Marks, “Myth,” p. 250.

39 Kagan, Origins, p. 345 for the “cult of the defensive” in French mentality; also Van Evera, “Cult of the Offensive,” pp. 58–107.

40 Gustav Stresemann, Nobel Lecture, “The New Germany,” June 29, 1927.

41 Kagan, Origins, pp. 313–14.

42 Shirer, Rise and Fall, p. 292.

43 Walter Rock, British Appeasement in the 1930s (London: Edward Arnold, 1977), p. 86.

44 Sunday Times, May 10, 1936, “Abyssinia’s Sad Fate,” by Scrutator. Cited in Benjamin Morris, The Roots of Appeasement: The British Weekly Press and Nazi Germany during the 1930s (London: Frank Cass and Co., 1991), p. 36.

45 The Tablet, Oct .4, 1930, cited in Morris, Roots, p. 39.

46 “Democracies and Dictatorships,” in The Tablet, Jan. 8, 1938. Cited in Morris, Roots, p. 39, emphasis added.

47 Geoffrey Dawson, writing to correspondent H. G. Daniels, May 23, 1937. Cited in Shirer, Rise and Fall, p. 396.

48 Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (New York: Penguin, 2004), p. 273. Kagan, Origins, p. 331.

49 Lamb, Drift, p. 89.

50 Winston Churchill, The Second World War, Volume 1: The Gathering Storm (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1948), pp. 271–72.

51 Kagan, Origins, p. 355.

52 Ralph Adams, British Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of Appeasement, 1935–39 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993), Appendix 1.

53 Shirer, Rise and Fall, p. 386.

54 Keylor, Legacy, p. 53.

55 Shirer, Rise and Fall, pp. 393–97; Rouse, Appeasement, pp. 6–7 on events of 1935.

56 Shirer, Rise and Fall, p. 391.

57 Kagan, Origins, p. 349, citing Craig, Germany, p. 691.

58 Shirer, Rise and Fall, p. 400. Kagan, Origins, p. 320 for Hitler, p. 349 on Jodl; citing P. Schmidt, Hitler’s Interpreter (London: Heinemann, 1951).

59 Victor Klemperer, I Will Bear Witness 1933–1941: A Diary of the Nazi Years, translated by Martin Chalmers (New York: Modern Library, 1999), pp. 155–56.

60 Ibid., p. 156.

61 Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, vol. 310, pp. 1435 f. Index at http://www.parliament.uk/hansard/hansard.cfm.

62 Kagan, Origins, 348.

63 Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates 310:1443.

64 Ibid., 1446, emphasis added.

65 Churchill, Gathering Storm, p. 263, from Schuschnigg’s record of the Austrian takeover, Ein Requiem in Rot-Weiss-Rot.

66 Ibid., p. 269.

67 Kagan, Origins, p. 385.

68 Ibid., p. 386.

69 Ibid., p. 379.

70 Overly, Road, p. 101; Neville Chamberlain, In Search of Peace (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1939).

71 Shirer, Rise and Fall, p. 521.

72 Churchill, Gathering Storm, p. 301; Kagan, Origins, pp. 285–86.

73 Churchill, Gathering Storm, p. 315.

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid., p. 319.

76 Kagan, Origins, p. 311.

77 Cited in OED, “appease”: 1.a. Works about appeasement include Paul Kennedy and Talbot Imlay, “Appeasement,” in The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered, 2nd ed., edited by Gordon Martel (New York: Routledge, 1999), pp. 116–34; Alfred L. Rowse, Appeasement: A Study in Political Decline (New York: Norton, 1960); Neville Thompson, The Anti-Appeasers: Conservative Opposition to Appeasement in the 1930s (Oxford: Clarendon, 1971).

78 Sir Archibald Sinclair, March 26, 1936, in Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates 310:1462.

[/groups_can]