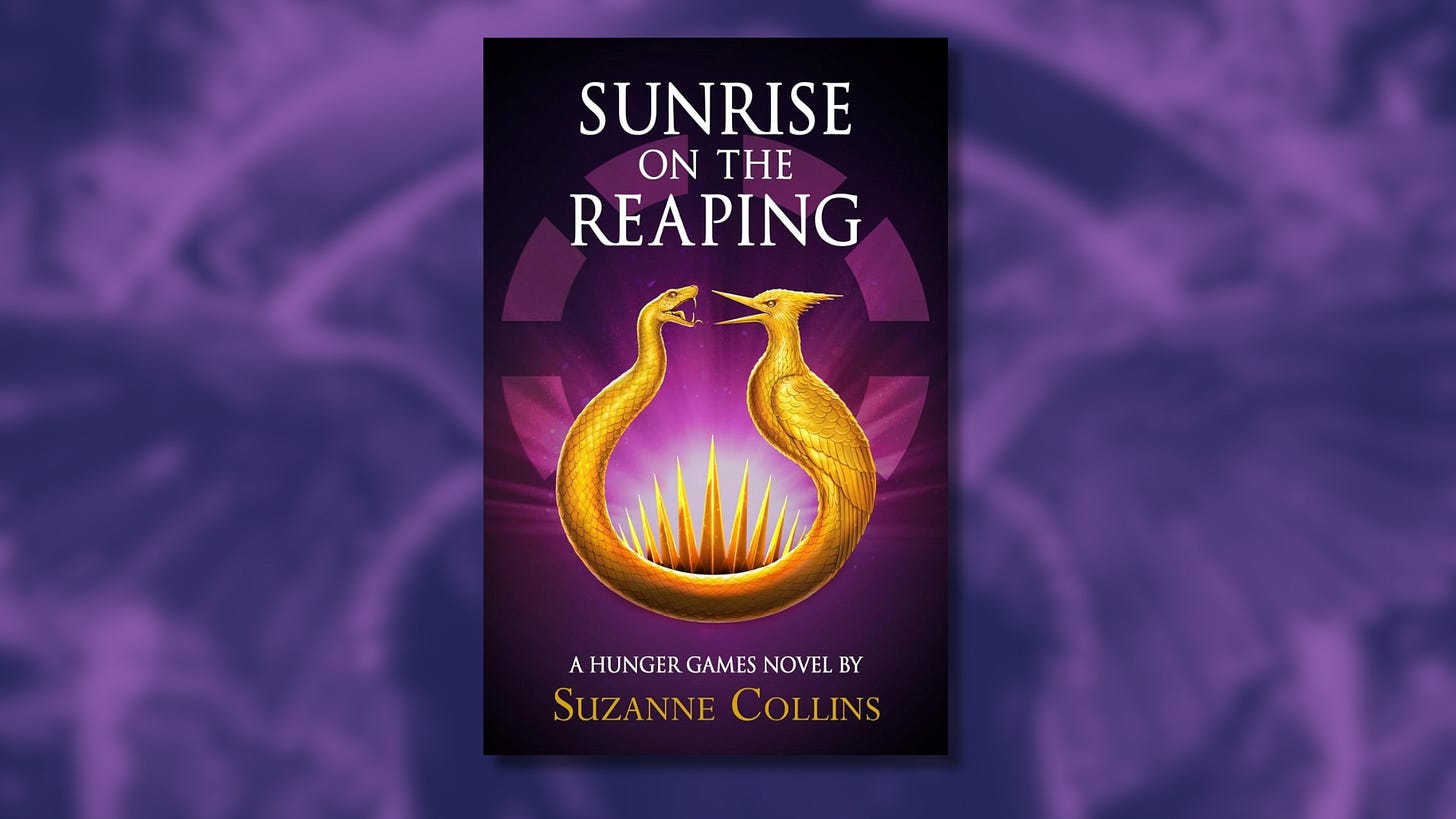

New York: Scholastic Press, 2025 400 pp., $19.17 (hardcover)

If you believed you were going to die soon, what would you do? If your death were to be public at the hands of a tyrant, how would you make your mark? These are the questions that Haymitch Abernathy, protagonist of Sunrise on the Reaping, asks himself when he is forced to fight in the fiftieth Hunger Games in which “tributes” (teenagers from each district of the fictional Panem) must fight until only one survives. This practice is the most visible instance of many forms of brutal oppression perpetrated by the government, referred to as the Capitol (which is also the name of the city in which it is based).

Sunrise on the Reaping is the latest entry in the Hunger Games franchise, taking place between the first prequel (The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, which was the villain origin story of the tyrannical President Snow) and the original trilogy. In the latter, Haymitch is a drunk who’s forced to mentor his district’s tributes each year—until the rebellion, of which he is part, ends the Hunger Games. Sunrise on the Reaping shows the tragic reasons he turned to drink, but more relevant to defenders of liberty, it also eloquently depicts the events that convinced him to join the rebellion.

The first spark comes from a conversation with his girlfriend about the Reaping, the ceremony in which the tributes are selected. She hates the Capitol and rails against the event. Haymitch, however, is resigned, telling her, “The Reaping’s going to happen no matter what I believe. Sure as the sun will rise tomorrow.” She disagrees: “There’s no proof that will happen. You can’t count on things happening tomorrow just because they happened in the past” (10). Her argument comes from a philosophically unreliable source: David Hume, who rejected causality.1 (We can perceive one event followed by another, perhaps repeatedly, but he argued that no logical connection exists between the two.) He wrote, “That the sun will not rise tomorrow is no less intelligible a proposition, and implies no more contradiction, than the affirmation, that it will rise.”2 What Hume ignored is that it’s possible to understand the causal mechanism for many observable phenomena, including sunrises.

But Haymitch and his girlfriend were using the Sun only as an analogy; the focus was on the Hunger Games. She argues that because people think that things will continue to be the way they always have been, they don’t even consider trying to change the system in which they live—which is why it persists despite its horrors.

Haymitch thinks about this conversation throughout the course of the novel, and he begins to understand which things are changeable and which aren’t. Some facts, such as that the Earth rotates and orbits the Sun, people will (probably) never be able to change. There’s no point in railing against these things but we should seek to understand them. Other facts, such as the existence of a particular government and its institutions, can be changed by men.

But the government of Panem doesn’t want its citizens to realize this critical distinction. In addition to well-armed troops and extensive surveillance, the government uses propaganda to give citizens the impression that its ubiquitous initiation of force is necessary for peace and prosperity and that government officials are more competent than they really are. The propaganda includes both the obvious kind—such as posters declaring “No Hunger Games, no peace” and “No Peacekeepers, no peace”—and more subtle forms (15, 60). These include using the state-run media to hide governmental failures and unjustifiable uses of force, such as when Plutarch (head game maker in Catching Fire but here an up-and-coming director) intentionally misrepresents the horrifying reality of the Reaping in District 12 (47). This motif not only reflects real life—governments, especially tyrannical ones, rely on such propaganda to keep themselves in power—it is also integrated with Haymitch’s journey of understanding better what he’s up against and what he can and can’t change.

Echoing Peeta in the first book, Haymitch knows that he’s not likely to survive the Hunger Games, but he doesn’t want to be just one more fatality for which the government takes no accountability. Peeta phrased it as wanting to show that he’s “more than just a piece in their Games.”3 In keeping with this book’s focus on propaganda, Haymitch develops his late father’s advice to “not let [the Capitol] paint their posters with your blood” into a determination to “paint his own poster” (49, 290). These metaphors are elegant in their simplicity, showing both characters to have a dedication to their own values in the face of a regime that denigrates the value of human life.

The kind of integrity that Haymitch and Peeta show is essential to anyone who wants to stand against immorality of any kind. In one instance of this, Haymitch spits in the face of Capitol citizens cheering on the grotesque parade that kicks off the Hunger Games. He shows them that he is not a prize pig going docilely to slaughter, and he does not want their applause or their support—even though these people have the ability to send him gifts in the arena that could save his life (80).

Some characters defend their values in more personal ways. Maysilee, one of the girl tributes from District 12, helps the other tributes fashion their tokens from home into jewelry they can wear into the arena (117). These tokens are the only things they have left from home and the only wearable signs of their personalities they’re allowed. Maysilee not only indulges her own appreciation of jewelry, but she helps other tributes display their values at a desperate time in their lives. This kind of determination—to offer some kind of public act of defiance or simply be one’s self as much as possible—makes the book inspiring despite its bleak backdrop.

Haymitch already hates the Capitol, having seen its injustice and cruelty from a young age. What he must learn is how such a mangled system filled with people detached from reality is propped up and that it can be brought down—because it is not a force of nature but man-made and changeable. Only with that understanding can he find even a glimmer of meaning and purpose when he’s suffered so much. His defiance and determination despite the tragedy make the novel an interesting and inspiring read for lovers of liberty.

That Collins was inspired by David Hume’s ideas is clear: Two of the novel’s four pre-quotes are from the Scottish philosopher, and she mentions in the book’s acknowledgment having conversations with her dad about Hume’s ideas.

This quote is used as a pre-quote for the novel; it is originally from David Hume’s “An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding,” https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-fmcc-philosophy1/chapter/david-hume-on-empiricism/.

Suzanne Collins, The Hunger Games (Scholastic: New York, 2008), Kindle edition, 141.