Editor’s note: This is an expanded version of a review that was first published on 22 January.

In early 1776, when many Americans still hoped for reconciliation with Britain, Thomas Paine published Common Sense, stripping monarchy of its pretenses and making the case for American independence. Later that year, as Washington’s army reeled from defeat, Paine opened The American Crisis with the reminder that “these are the times that try men’s souls,” urging perseverance when retreat seemed tempting. His purpose was straightforward: to name a crisis, state its moral stakes, and rally free people to act.

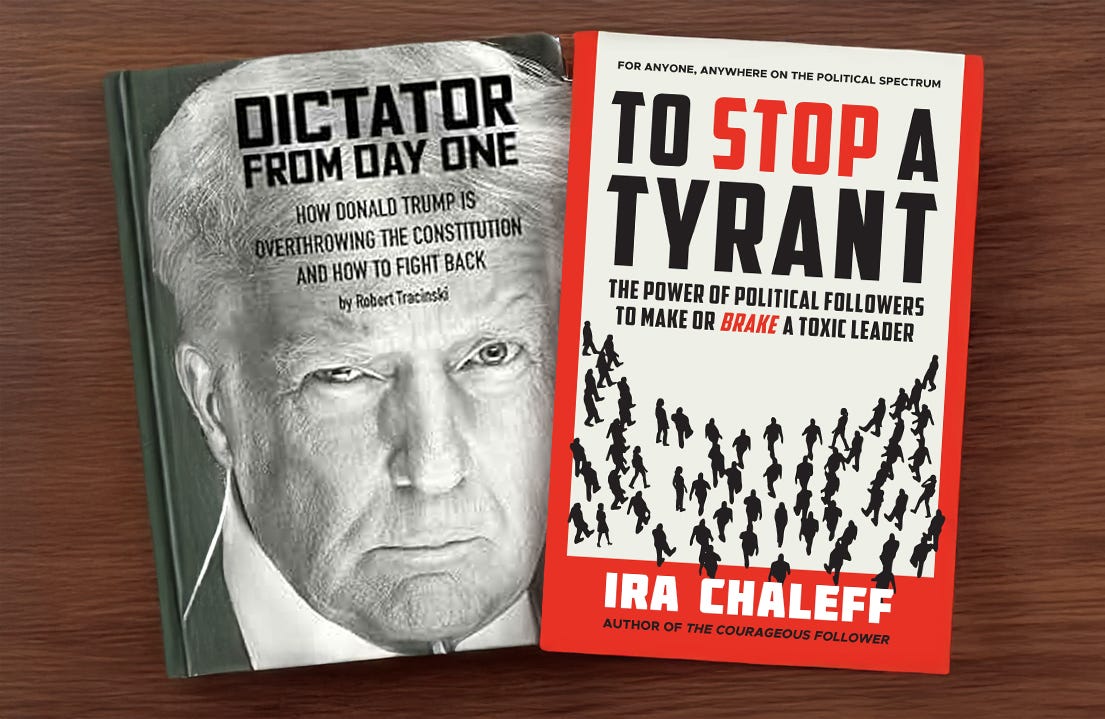

We face similar problems today: widespread denial of reality in various ways, political tribalism, institutional decay, and a growing threat to constitutional government that many dismiss as routine partisanship. Robert Tracinski’s book, Dictator from Day One: How Donald Trump Is Overthrowing the Constitution and How to Fight Back, offers solutions to these problems. While many Americans minimize Trump’s abuses—his defiance of legal limits, attacks on independent courts, and personal use of presidential power—Tracinski makes an especially alarming point: “We are not risking a constitutional crisis. The crisis is already here. In many cases, the constitutional crisis has already passed, and the Constitution lost” (125).

For decades, most major intellectual and political movements have turned away from the principles that sustain a free society. So-called “Progressives” have elevated egalitarian collectivism over individual rights, attempting to redefine justice as overt racism, sexism, and the “soft bigotry of low expectations” rather than treating people as their actions warrant. Conservatives—failing to defend individualism and capitalism on secular, principled grounds—retreated into faith, nationalism, and a politics more reactionary than principled. The result is the moral cesspool that enabled Donald Trump’s rise.

As Tracinski argues, Trump is not a bulwark against cultural decline but its embodiment; he is evasion of reality, resentment, and abandonment of principle concentrated in a single person. Trump’s appeal lies in a false vision of liberty or law, and in the real emotional rewards of tribal combat and the spectacle of a leader who promises to punish the tribe’s enemies. Tracinski grounds his argument in concrete, repeated actions that reveal a governing premise incompatible with constitutional restraint. Trump does not merely test the boundaries of executive power; he explicitly denies that such boundaries exist at all. Tracinski interprets Trump’s assertion that Article II allows him to do “whatever I want as president” as a statement of governing principle: that presidential power is personal, discretionary, and unconstrained by law. As Tracinski puts it, Trump “is already exercising power on his personal whim, unchecked by other branches or organs of government” (12).

Trump put his governing principle into practice when he ordered executive officials to defy congressional subpoenas wholesale—not through particularized claims of executive privilege, but by rejecting Congress’s authority to investigate him at all. Tracinski emphasizes that Trump’s posture was not a routine separation-of-powers dispute but an attempt to render Congress irrelevant, to “knock down any competing center of power, any barrier or check against the dictator” (14). The issue, he insists, is not partisan conflict but the concentration of power in a single person.

The same governing logic governs Trump’s treatment of the courts. When judges enjoined unlawful executive actions, Trump did not engage their reasoning; he attacked their legitimacy, dismissing them as partisan actors—“Obama judges”—and treating judicial review itself as political interference. Tracinski documents repeated instances in which court orders were ignored, delayed, or met with deception and open contempt, including defiance of unanimous Supreme Court rulings in immigration cases. This is why Tracinski describes the emerging legal regime as “Calvinball jurisprudence,” a system in which “there are no fixed rules” except that “this administration always wins” (72).

Trump applied this logic most aggressively to law enforcement and the legal system itself. Tracinski details how Trump treats prosecutorial authority as an instrument of personal loyalty, pressuring officials to protect allies and pursue perceived enemies. He further documents Trump’s use of executive power to intimidate and neutralize the legal profession—revoking security clearances, canceling government contracts, and imposing economic penalties on law firms that represented Trump’s critics. The result, Tracinski warns, is a system in which “opponents will have no right to mount a defense in court, while [the president’s] allies will have the right to unlimited legal support” (76). In parallel, Trump asserted control over congressionally appropriated spending, conditioning the release of funds on personal or political favor and reversing the Constitution’s allocation of the power of the purse.

For Tracinski, these actions are not isolated abuses or excesses of temperament. Taken together, they constitute a coherent pattern: the systematic replacement of objective law with discretionary, personal rule. That system, Tracinski argues, is not a speculative future danger but a present reality already underway—asserted, normalized, and advancing, though not yet fully entrenched.

To Tracinski, Trump’s quest for personal power would not be possible in a culture that broadly understood liberty and individual rights. Trump’s rise thus reflects a deeper cultural surrender; when a culture no longer understands or values liberty, it turns instead to authoritarians, accepting whim over principle and loyalty over law as substitutes for a rights-respecting government.

Tracinski’s central insight is that authoritarianism does not arrive all at once and rarely takes the form citizens expect. It emerges gradually, as rights-respecting legal institutions lose their capacity to constrain power, and the behaviors that support a free society erode. He states: “It’s not something that will happen or might happen. It is a present reality, not a mere future possibility. But it is something that is still going on and not complete” (12). That slow corrosion—rather than a single dramatic rupture—is the danger he asks readers to confront.

Ira Chaleff’s To Stop a Tyrant: The Power of Political Followers to Make or Break a Toxic Leader offers a complementary perspective. Unlike Tracinski, Chaleff does not analyze any specific contemporary political leader; instead, his focus is on tyranny in the abstract and the ethical responsibilities of followers within hierarchical institutions, regardless of context. Whereas Tracinski focuses on the constitutional and moral dimensions of creeping authoritarianism, Chaleff examines how subordinates enable or resist destructive leadership. As he warns,

When fires are small, we can smother them with a blanket or a bucket of sand. When they become conflagrations, all we can do is escape with our lives, retreat, and attempt to create fire breaks. So it is with the escalation of a leader with authoritarian tendencies to one who becomes a full-blown tyrant (25).

Chaleff’s emphasis is on timing and responsibility: the cost of delay, and the way ordinary acts of compliance can harden into laws and precedents that are difficult or impossible to reverse. “The unique lens of this book is its focus not on the tyrant, but on their followers,” says Chaleff. “However destructive tyrants are, they would be impotent without followers, willing or coerced to execute their designs” (18).

The contrast between the two books is instructive. Chaleff writes to those navigating hierarchical structures, emphasizing that “early resistance is required to emerging tyrannical behavior—not just when the leader reaches the apex of the political pyramid, but at every stage of their ascendance” (275). Here, Chaleff is explicit that tyrants do not rule alone. In contrast, Tracinski writes to citizens confronting a threat to the political framework of a free society. Chaleff offers tools for resisting within organizations, insisting that “followership is tested at its moral core” when power turns abusive (187). He rejects moral passivity outright, arguing that in such circumstances “‘just following orders’ is itself a crime” (187), and calls instead for what he terms “courageous followers,” who “seek ways to counteract the toxicity, including removing the destructive leader if necessary” (21). Tracinski, by contrast, offers a moral and philosophic case for resisting emerging authoritarianism at the level of constitutional government—and why such resistance is necessary in the first place. Together, the books illuminate both the individual and institutional failures that enable tyranny to grow—and the principles that must be revived if liberty is to be preserved.

What makes Dictator From Day One especially valuable is that Tracinski does not treat today’s authoritarian drift as primarily a matter of partisan tribalism or executive overreach, although both are real and major factors. He instead roots the problem in a deeper abandonment of principle: the erosion of objective law itself. From that diagnosis follows his central prescription: “To oppose Trump, we need a spirit that we might call militant liberalism”—a stance defined by confronting abuses early, consistently, and without apology (137). His argument is not for violence but for a rational and consistently principled approach—to insist that no violation of constitutional limits is too small to contest. In a system that depends on citizens holding politicians accountable, passive hope that problems will solve themselves is surrender. “The habit of normal politics is to pick our battles and look for a measured response in order to appear moderate and ‘reasonable,’” says Tracinski. “But in the current context, the more moderate we appear, the more this assures everyone that we are still in normal times, not in a crisis.” (125)

Dictator From Day One is a vital book precisely because it aims to do what many readers most resist: confronting the reality that the constitutional crisis is well underway. As Tracinski explains, “The purpose of this book is to grab its readers and shake them awake” (1). It is a warning—one meant “to show the scope, speed, and detail with which we are being sold into serfdom” (4). Rather than promising that norms or institutions will save themselves, the book challenges readers to acknowledge the crisis, confront it, and recover—or discover—the vigilance that a free society requires while resistance remains possible.

Chaleff’s contribution should not be overlooked, especially for those working within government, the military, or other large organizations where pressures toward conformity can be immense. He focuses on how tyranny is enabled—or resisted—inside institutions themselves, warning that “the autocrat counts on the bureaucratic culture to do his bidding and dirty work: to be conformist followers” (65). For Chaleff, ethical dissent is not merely refusal but active counteraction, often by exposing abuses, since “the more this can be done in full ‘sunlight,’ the harder it will be for the prototyrant to nullify principled bureaucrats” (188). This emphasis on ethical dissent from within institutions is a valuable complement to Tracinski’s broader, principle-based argument. But it is Tracinski who names the stakes for the American republic itself.

The essential choice these books present is not between left and right or between competing policy agendas. It is the choice between a political order bound by objective law and one defined by whim, leading to widespread violations of rights. Chaleff shows how tyranny gathers helpers—warning that “conformist followers go about their business, falling in line with whatever dictates emanate from the toxic leader” (278). Tracinski shows why it must not prevail. A free society depends on citizens who refuse to excuse abuses merely because they come from their preferred political party, and who recognize that every concession to arbitrariness weakens the political framework that protects their own lives and liberties.

Read Chaleff to understand how individuals can and should navigate moral choices inside compromised institutions. Read Tracinski to grasp both the principles at stake and the only form of resistance adequate to a constitutional crisis: public, principled, and uncompromising opposition to the erosion of objective law. Taken together, the two books are illuminating—but if one is forced to choose, it is Tracinski’s account that proves decisive, because it identifies both the nature of the crisis and the kind of resistance a free society requires.

Whatever you take from these books, choose to act—not from fear or partisanship, but from the conviction that your life is yours by right, and that a free republic remains worth defending while the means to do so remain.

This article appears in the Spring 2026 issue of The Objective Standard.

A few examples would help me understand what the author means by Trump’s “defiance of legal limits, attacks on independent courts, and personal use of presidential power”

“Trump is already exercising power on his personal whim, unchecked by other branches or organs of government." How and when? An example to illustrate may help convince someone of your assertion that Trump is a dictator.